Back in December, I predicted that Microsoft wouldn’t release the Project Spartan beta until it bested all of its competitors on the major benchmarks: SunSpider, Kraken, and Octane. I was wrong—the first beta was released with only minor script performance improvements. That changed with build 10061 of Windows 10, and Spartan now does beat everyone else on their own benchmarks.

Running Windows 10 on my new 2015 Dell XPS13 i5-5200U, I get the following scores:

| Browser |

SunSpider |

Kraken |

Octane |

| Spartan/IE 10061 |

122.7ms |

1444.44ms |

23652 |

Chrome 43

beta 2357.37 |

255.5ms |

1557.7ms |

22656 |

| Firefox 37.0.2 |

204.2ms |

1498.4ms |

21762 |

Now, some of these “victories” are within the margin of error, and it’s very possible that upcoming versions of Chrome and Firefox will improve their performance on slow outliers (e.g. Chrome’s score on Octane’s MandreelLatency is just 22% as fast as Spartan’s). But anyone surprised at Microsoft’s great results is overlooking the fact that some of the world’s best compiler developers and architects work for Microsoft and their attention has increasingly been turned toward JavaScript.

Of course, script performance is important, but it’s far from the only way to measure a browser. Standards-compliance, network performance, ease-of-use, security, end-user features and many other aspects determine your experience with a browser. There are many different tests (subjective and less-subjective) for these aspects, although each has its own biases. But just to give one example, with all its feature flags turned on, Spartan ekes out a score of 402/555 on the (questionable, but easily run) HTML5Test.com while Firefox and Chrome score 449 and 526 respectively.

Hamstringing JavaScript

Of course, your numbers might be wildly different than those above, for one major reason: security software.

Every year for Microsoft’s annual AV summit, the IE Team puts together a chart of the impact of AV on browser performance, showing the variation across the top 20 AV products (the variation is huge). They don’t want to publish this data, but the impact ranges from “bad” to “absurdly unbelievably bad.” The best products impact performance by ~15%, the worst slow the browser by 400% or more. Several of the products crash the browser entirely and can’t be benchmarked fully. Conducting these benchmarks correctly is difficult—you need to account for every piece of software running on the machine and ensure that the test conditions are entirely fair (hardware, software, updates, etc); as a consequence, many of the “public” benchmarks are rather inaccurate.

Why hasn’t the IE team released their numbers? My guess is that it’s to try not to anger the AV companies, all of whom have been muttering “antitrust antitrust antitrust” under their collective breath ever since Microsoft integrated an entirely decent antivirus package into Windows 8.

Personal anecdote: I have Symantec Endpoint Protection running on a machine with a high-end i7-4771 CPU; even after unticking all of the “optional” protection features I can find in the Symantec control panel, the Octane score in Chrome 43 is 11659. On the same hardware in the same browser version without Symantec installed, the Octane score is 32555, 279% of the original score.

The devastating impact of antivirus on browsing performance is one reason why your portable devices feel magically fast—on a AV-unhindered i7, IE11 runs SunSpider in 70ms. Add AV and it runs in 350ms. The IPad Air, running with Safari’s slower script engine, runs it in 380ms. Mobile devices offer “Desktop Class” performance only because your desktop has been wrecked.

Antivirus software is too often a cure that’s as bad as the disease. The business model of AV rewards noisy products, and the desire for “checkbox parity” leads to a race to shove its tentacles in all sorts of places they don’t belong (e.g. the internal data structures of the browser). Unfortunately, even beyond antitrust concerns, Microsoft is very limited in its ability to deal with horrible AV products due to court precedents that say that AV can pretty much get away with doing anything it wants in the name of “protecting the user.”

You might ask: “Without my security software, aren’t I at risk?”

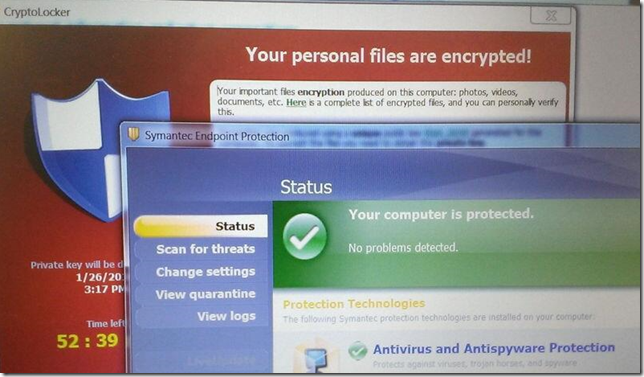

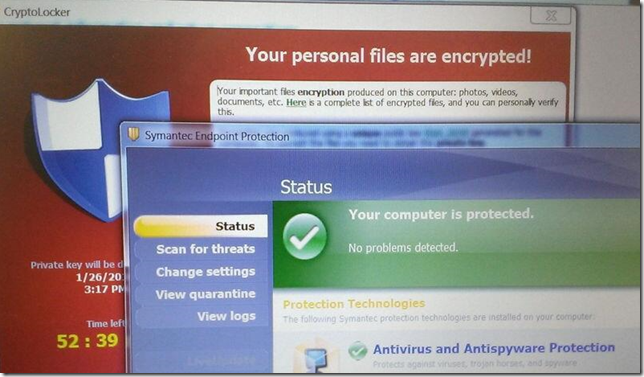

Yes, you are. But security software provides surprisingly little protection, as this delightful photo of a colleague’s laptop shows. In the foreground, the AV software promising that the user is protected. In the background, the ransom UI demanding payment to decrypt the documents that have just been mangled.

Even worse, “security” software itself often introduces vulnerabilities into otherwise secure systems.

Advice

Want to be protected and stay fast?

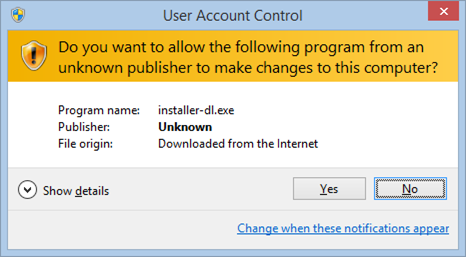

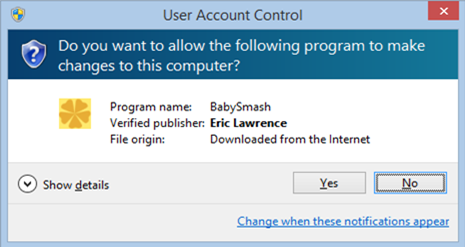

- Upgrade to Windows 8.1 or later.

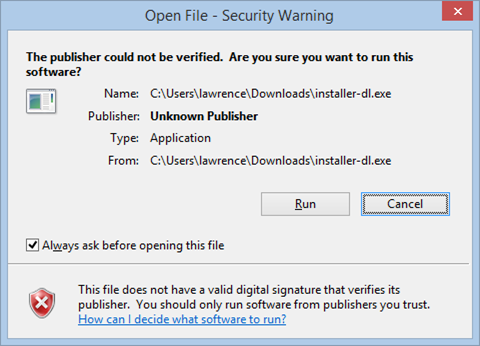

- Leave SmartScreen Application Reputation enabled.

- Leave the built-in antivirus enabled.

Or get a Chromebook.

– Eric Lawrence