I did a reasonably good job running on my treadmill throughout the fall of 2025, in preparation for my second summit of Mount Kilimanjaro over New Years (blog post to come).

Run for the Water 10 Miler

On November 9th, 2025, I ran the ten mile Run for the Water.

The night before, I ate spaghetti and meat sauce with the kids for dinner. Went to bed early (around 10) but slept poorly, waking up every few hours. Woke at 445 but managed to doze for another dream before my alarm went off at 5am. Had a banana and a gassy but not very useful trip to the bathroom. Put on a “Run the mile you’re in” temporary tattoo and posted the pic to Facebook where two members of my family thought it might be real. 😂

The weather was 57F and breezy, but super-sunny. I left the house at 6:10, got to my usual parking space at 6:30, and had time for a quick stop at the pre-race porta potty. My marshmallow-y supershoes (carbon plate) were comfy for the whole race.

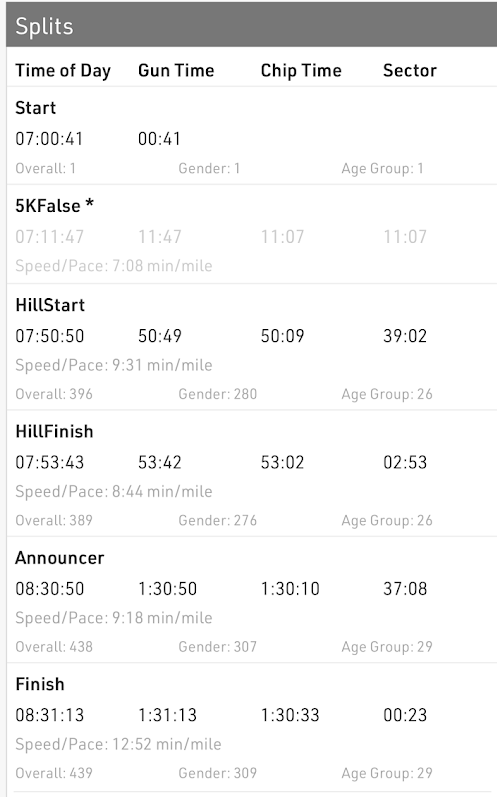

I did okay. I wanted to beat my best time (1:28:57), which I decided would be really hard. So I was kinda just aiming to beat 1:30. I got 1:30:33, just a minute and a half slower than my record, and a blazing 34 minutes faster than my glacial 2024 attempt.

Had I known I was that close, I know I coulda beat 1:30 pretty easily, and almost certainly PR’d to boot.

But I feel mostly fine about the race– I worked hard and nothing in particular hurt or felt bad. My watch failed to hold a connection to the cross-body left headphone so I put it in my pocket. What I didn’t realize was that the body of the headphone was a button that, when tapped, lowered the volume, so I ended up running for a frustrating mile or two with no music yet again.

This time, the “giant” hill at mile 5.5 did not seem giant at all; I’m not sure it was even the biggest hill of the course.

Austin International Half Marathon

On January 18th, I had my fourth run of the Austin International Half, finally meeting my sub-two-hour goal with a finish in 1:56:31. There were about 4200 runners this year.

The night before, I ate spaghetti, meat sauce, and garlic bread with the kids somewhat early, and got to sleep around 10:30. I woke at 4am before dozing again until just before my 5:15 alarm. I ended up pulling out of my driveway by 6:35 and made good time to my usual parking spot in the Stonelake garage. A quick trip to the porta potty went well (no line that early) and I then spent fifteen minutes keeping warm in the car.

I was in my tights, jacket, and disposable cloth gloves (which i kept after I took off around mile 7). The wind was mild, so the low temp (30F) wasn’t too awful.

I had a great start, running with the 1:50 pacers for 5.5 miles. I fell behind and lagged a bit between the 10K and the halfway point, but the fear of the 1:55 pacer passing me from behind kept me running. Around mile 9, the 1:55 pacer caught up and I only managed to stay with them for half a mile or so before falling behind again. But the smell of the finish line was in my imagination and I only walked for half of the two hills downtown. I finished in 1:56:31, just over four minutes faster than my 2023 PR and 22 minutes faster than last year.

I waited in line for a solid ten minutes to hit the PR gong for the first time ever. I felt good throughout the race, with only a minute or so worth of worry about the rumble in my belly.

I’m very happy with this outcome.

Galveston Half Marathon

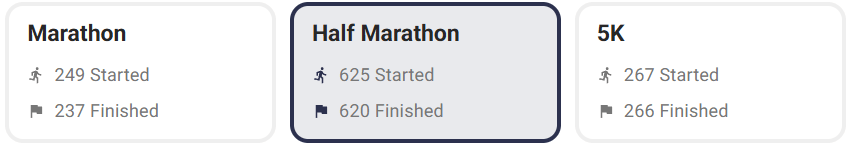

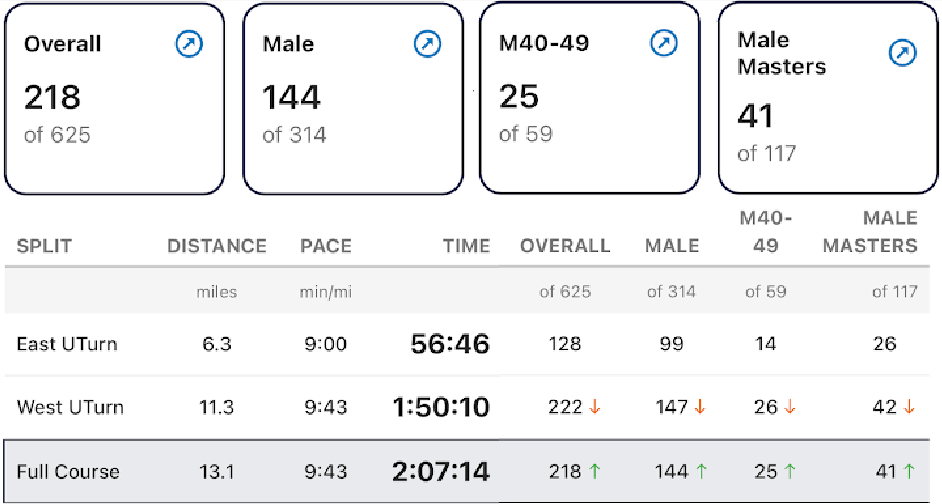

The Galveston Half was moved another week earlier this year, with a predicted start temperature of 37F, well below 2025’s 64F. There were 625 half marathon runners this year.

While I knew I wouldn’t replicate my recent Austin Half results, I definitely hoped to get my fastest time for this course, and ideally, breaking 2 hours again would be amazing.

Fortunately, the somewhat stronger wind didn’t make things feel too cold, and the clear skies warmed things up fast enough that I dropped my hoodie just before mile 4 and my gloves went in my pocket at mile 8 or so.

I remembered the course well having run it four times before (twice for last year’s half), and there were no surprises in how I felt. I started with the 1:50 pacer but only kept up for around 3 miles before falling behind the 1:55 pacer and 2:00 pacer shortly after. But I still managed to stay on the move, with limited bits of walking around the aid stations and a 30 second pause to pee behind the single occupied porta-potty found at mile 6.

My 2:07 finish was a solid 7 minutes faster than my first two attempts, and almost 32 minutes faster than the first half of last year’s full. It wasn’t quite the result I’d hoped for, but I’m counting the PR for this course as a big enough win.

In April, I run the Capitol 10K again and hope to PR (it’s gonna be hard), and on the first Sunday in May I’ll revisit the Sunshine Run (where I had better beat my unimpressive record for that course).

-Eric