Software developers and end-users are often interested in understanding how to resolve incorrect detections from their antivirus/security software, including Microsoft Defender.

Such False Positives (FPs) can disrupt your use of your device by incorrectly blocking innocuous files or processes. However, you should take extreme care before concluding that a given detection is a false positive — attackers work hard to make their malicious files seem legitimate, and your security software is built by experts who work hard to flag only malicious files.

How Do False Positives Occur?

Every security product must perform the difficult task of maximizing true positives (protecting the user/device) while minimizing false negatives (protecting productivity/data). The resulting ratio is called security efficacy.

False-positives can occur for numerous reasons, but most are a result of security software observing what it deems to be suspicious content or behavior on the part of a file or process. Virtually all modern security software consists of a set of signatures and heuristics that attempt to detect indications of malice based on threat intelligence data collected and refined by threat researchers (both humans and automated agents). In some cases, the threat intelligence is scoped too broadly and incorrectly implicates harmless files along with harmful ones.

To correct this, the threat intelligence from your security vendor must be adjusted to narrow the detection so that it applies only to truly malicious files.

Sidenote: Is it really a block?

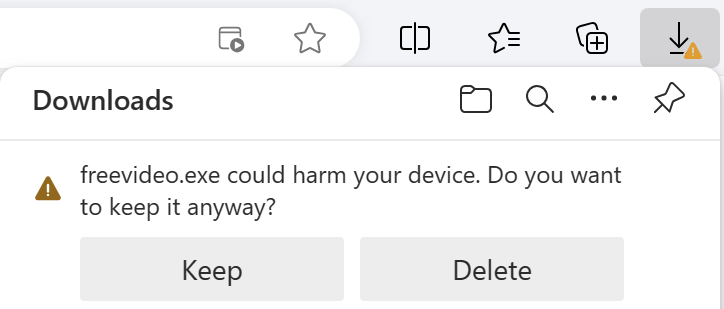

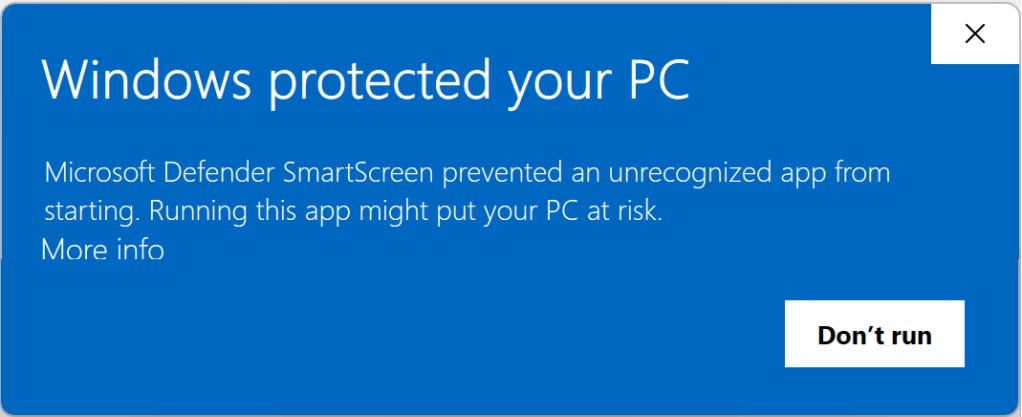

In some cases a security feature might block a file not as malicious but merely as uncommon; for example, SmartScreen Application Reputation can interrupt download or starting of an app if the app isn’t recognized:

In such cases, users may choose to ignore the risk and continue if they have good reason to believe that the file is safe. Over time, files should build reputation (especially when signed, see below) and these warnings should subside for legitimate files.

False Positives for End-Users

Before submitting feedback, it’s probably worthwhile to first confirm what security product is triggering a block. In some cases, blocks that look like they may be coming from your security software might actually reflect intentional blocks from your network security administrator. For example, users of Microsoft Defender for Endpoint should review this handy step-by-step guide.

To get a broader security ecosystem view of whether a given file is malicious, you can check it at VirusTotal, a free service which will scan files against most of the world’s antivirus engines and which allows end-users to vote on the safety of a given file.

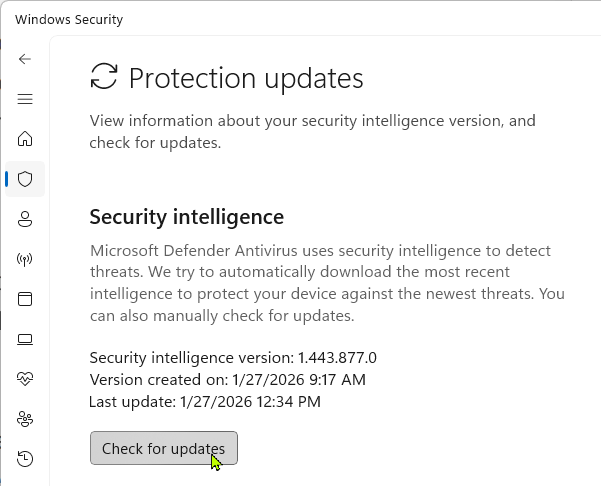

When a security vendor realizes a false positive has occurred, they will typically issue a signature update; while this typically happens entirely automatically, you might want to try updating your signatures just to ensure they’re current.

False positives (and false negatives) for Microsoft Defender Antivirus can be submitted to the Defender Security Intelligence Portal; these submissions will be evaluated by Microsoft Threat researchers and detections will be created or removed as appropriate. Other vendors typically offer similar feedback websites.

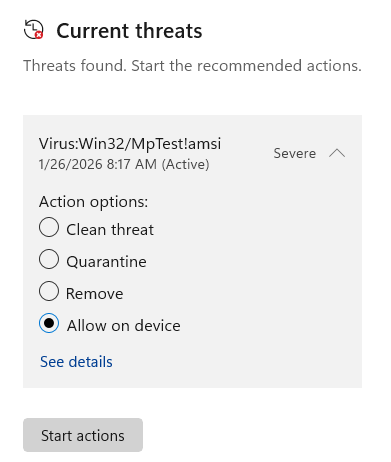

In most cases, users may override incorrect detections (if they are very sure they are false positives) using the Windows Security App to “Allow” the file or create an exclusion for its location.

Avoiding False Positives for Software Vendors

If you build software, your best bet for avoiding incorrect detections is to ensure that your code’s good reputation is readily identifiable for each of your products’ files.

To that end, make sure that you follow Best Practices for code-signing, ensuring that every signable file has a valid signature from a certificate trusted by the Microsoft Trusted Root Program (e.g. Digicert, Azure Trusted Signing).

If your files are incorrectly blocked by Microsoft Defender, you can submit a report to the Defender Security Intelligence Portal.

-Eric