In a recent post, I explored some of the tradeoffs engineers must make when evaluating the security properties of a given design. In this post, we explore an interesting tradeoff between Security and Privacy in the analysis of web traffic.

Many different security features and products attempt to protect web browsers from malicious sites by evaluating the target site’s URL and blocking access to the site if a reputation service deems the target site malicious: for example, if the site is known to host malware, or perform phishing attacks against victims.

When a web browser directly integrates with a site reputation service, building such a feature is relatively simple: the browser introduces a “throttle” into its navigation or networking stack, whereby URLs are evaluated for their safety, and a negative result causes the browser to block the request or navigate to a warning page. For example, Google Chrome and Firefox both integrate the Google Safe Browsing service, while Microsoft Edge integrates the Microsoft Defender SmartScreen service. In this case, the privacy implications are limited — URL reputation checks might result in the security provider knowing what URLs are visited, but if you can’t trust the vendor of your web browser, your threat model has bigger (insurmountable) problems.

However, beyond direct integration into a browser, there are other architectures.

One choice is to install a security addon (like Microsoft Defender for Chrome or Netcraft) into your browser. In that case, the security addon can collect navigating/downloading URL using the browser’s extension API events and perform its task as if its functionality was directly integrated into the browser. Similarly, Apple offers a new platform API that allows client applications to report URLs they plan to fetch to an extensible lookup service that allows a security provider to indicate whether a given request should be blocked.

In the loosest coupling, a security provider might not integrate into a web browser or client directly at all, instead providing its security at another architectural layer. For example, a provider might watch unencrypted outbound DNS lookups from the PC and block the resolution of hostnames which are known to be malicious. Or, a provider might watch network connections to an outbound site and block connections where the URL or hostname is known to be malicious. This sort of inspection might be achieved by altering the OS networking stack, or plugging into an OS firewall or similar layer.

A common choice is to configure all clients to route their traffic through a proxy or VPN that breaks TLS as a MitM (e.g. Entra Internet Access) and provides the security software access to unencrypted traffic.

The decision of where to integrate security software is a tradeoff between context and generality. The higher you are in the stack, the more context you have (e.g. you may wish to only check URLs for “active” content while ignoring images), while the lower you are in the stack, the more general your solution is (it is less likely to be inadvertently bypassed).

The advantage of integrating security software deep in the OS networking layer is that it can then protect any clients that use the OS networking stack, even if those clients aren’t widely known, and even if the client was written long after your security software was developed. By way of example, Microsoft Defender’s Network Protection and Web Content Filtering features rely upon the Windows Filtering Platform to inspect and block network connections.

For unencrypted HTTP requests, inspecting traffic at the network layer is easy — the URL is found directly in the headers on the outbound request, and because the HTTP traffic is unencrypted plaintext, parsing it is trivial. Unfortunately for security vendors, the story for encrypted HTTPS traffic is much more complicated — the whole point of HTTPS is to prevent a network intermediary (including a firewall, even on the same machine) from being able to read the traffic, including the URL.

To spy on HTTPS from the networking level, a security vendor might reconfigure clients to leak encryption keys, or it might rely on a longstanding limitation in HTTPS to sniff the hostname from the Client Hello message that is sent when the client is setting up the encrypted HTTPS channel with the server.

Security products based on sniffing network traffic (DNS or server connections) are increasingly encountering a sea change: web browser vendors are concerned about improving privacy, and have introduced a number of features to further constrain the ability of a network observer to view what the browser is doing. For example, DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) means that browsers will no longer send unencrypted hostnames to the DNS server when performing lookups. Instead, a secure HTTPS connection is established to the DNS server, and all requests and responses are encrypted to hide them from network observers.

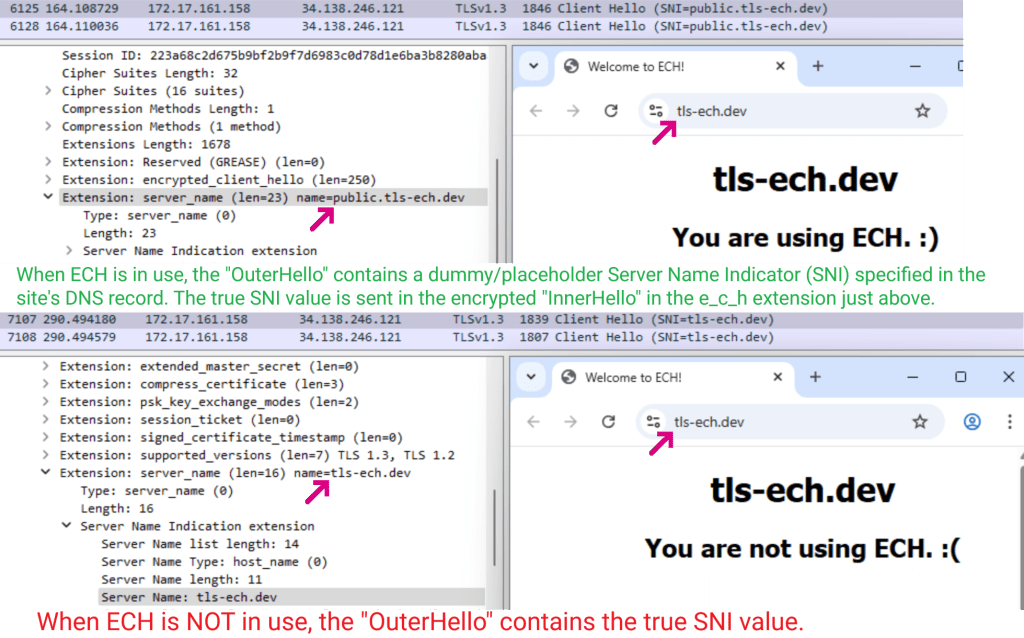

Additionally, a new feature called Encrypted Client Hello (ECH) means that browsers can no longer spy on the first few packets of a TLS connection to see what server hostname was requested. For example, in loading the https://tls-ech.dev test page with ECH enabled, the client sends a “decoy” Server Name Indicator (SNI) of public.tls-ech.dev rather than the real server name:

When a browser looks up a domain in DNS, the HTTPS Resource Record declares if ECH should be used and if so, the decoy SNI value to send in the OuterHello. You can see this record using a DNS viewer like https://dns.google:

Both Chromium and Firefox have support for ECH. Originally, both DoH and ECH were disabled-by-default in Chrome, Edge, and Firefox for “managed” devices but it appears this may have changed. A test site for ECH can be used to see whether your browser is using ECH, and you can follow these steps to see if a server supports ECH.

A growing percentage of servers support HTTP3/QUIC, an encrypted protocol that runs over UDP. QUIC’s use of “initial encryption” precludes trivial extraction of the server’s name from the UDP packet.

Blinded by these privacy improvements, a security product running at the network level may be fooled and might be forced to fall back to only IP reputation, which suffers many challenges.

Unfortunately, this is a direct tradeoff between security and privacy: security products that aren’t directly integrated into browsers cannot perform their function, but disabling those privacy improvements means that a network-based observer could learn more about what sites users are visiting.

Browser Policies

Browsers offer policies to allow network administrators to make their own tradeoffs by disabling security-software-blinding privacy changes.

Chrome

- DNS-over-HTTPS (already disabled by default on “Managed” devices)

- Encrypted Client Hello (currently, ECH on Windows and Linux requires DoH aka “Secure DNS”; testing shows that ECH can be used on Mac when DoH is off.)

- QUIC (HTTP3); products that only support HTTPS-over-TCP/IP cannot analyze QUIC traffic.

Edge

- DNS-over-HTTPS (already disabled by default on “Managed” devices)

- Encrypted Client Hello (currently, ECH on Windows and Linux requires DoH aka “Secure DNS”)

- QUIC (HTTP3); products that only support HTTPS-over-TCP/IP cannot analyze QUIC traffic

Firefox

- DNS-over-HTTPS (already disabled by default on “Managed” devices)

- Disabling DNS-over-HTTPS also disables ECH because Firefox demands DoH retrieval for data used in ECH

- QUIC can be disabled by setting a networking preference (

network.http.http3.enable) via policy

Safari

- Current versions of Safari reportedly do not offer a policy to disable QUIC. You may be successful in blocking QUIC traffic at the firewall level (e.g. block UDP traffic to remote port 443).

Stay safe out there!

-Eric

PS: It’s worth understanding the threat scenario here– In this scenario, the network security component inspecting traffic is looking at content from a legitimate application, not from malware. Malware can easily avoid inspection when communicating with its command-and-control (C2) servers by using non-HTTPS protocols, or by routing its traffic through proxies or other communication channel platforms like Telegram, Cloudflare tunnels, or the like.

PPS: Integrating into the browser itself may also be necessary to block sites in situations where a site doesn’t require the network in order to load.

PPPS: Sniffing the SNI is additionally challenging in several other cases:

1) If the browser uses QUIC, the HTTP/3 traffic isn’t going over a traditional TLS-over-TCP channel at all.

2) If the browser is using a VPN service (or equivalent), then the web traffic’s routing information is encrypted before reaching the network stack, and the ClientHello is encrypted and thus the SNI cannot be read.

3) If the browser is connected to a Secure Web Proxy (e.g. TLS-to-the-proxy itself, like the Edge Secure Network feature) then the traffic’s routing information is encrypted before reaching the network stack and ClientHello is encrypted and thus the SNI cannot be read.

4) If the browser uses H/2 Connection coalescing, the browser might reuse a single HTTP/2 connection across multiple different origins. For example, if your admin blocks sports.yahoo.com, you can get around that block by first visiting www.yahoo.com, which creates an unblocked HTTP/2 connection that can be later reused by requests to the Sports.yahoo.com origin.

While an enterprise browser policy is available to disable QUIC, there is not yet a policy to disallow H2 coalescing in Chromium-based browsers. In Firefox, this can be controlled via the network.http.http2.coalesce-hostnames preference.