Fundamentals are invisible. Features are controversial.

One of the few common complaints against Microsoft Edge is that “It’s bloated– there’s too much stuff in it!”

A big philosophical question for designers of popular software concerns whether the product should include features that might not be useful for everyone or even a majority of users. There are strong arguments on both sides of this issue, and in this post, I’ll explore the concerns, the counterpoints, and share some thoughts on how software designers should think about this tradeoff.

But first, a few stories

- I started working in Microsoft Office back in 1999, on the team that was to eventually ship SharePoint. Every few months in the early 2000s, a startup would appear, promising a new office software package that’s “just the 10% of Microsoft Office that people actually use.” All of these products failed (for various reasons), but they all failed in part because their development and marketing teams failed to recognize a key fact: Yes, the vast majority of customers use less than 10% of the features of the Microsoft Office suite, but it’s a different 10% for each customer.

- I started building the Fiddler Web Debugger in 2003, as a way for my team (the Office Clip Art team) to debug client/server traffic between the Microsoft Clip Art client app and the Design Gallery Live webservice that hosted the bulk of the clipart Microsoft made available. I had no particular ambitions to build a general purpose debugger, but I had a problem: I needed to offer a simple way to filter the list of web requests based on their URLs or other criteria, but I really didn’t want to futz with building a complicated filter UI with dozens of comboboxes and text fields.

I mused “If only I could let the user write their queries in code and then Fiddler would just run that!” And then I realized I could do exactly that, by embedding the JScript.NET engine into Fiddler. I did so, and folks from all over the company started using this as an extensibility mechanism that went far beyond my original plans. As I started getting more feature requests from folks interested in tailoring Fiddler to their own needs, I figured “Why not just allow developers to write their own features in .NET?” So I built in a simplistic extensibility model that allowed adding new features and tabs all over. Over a few short years, a niche tool morphed into a wildly extensible debugger used by millions of developers around the world.

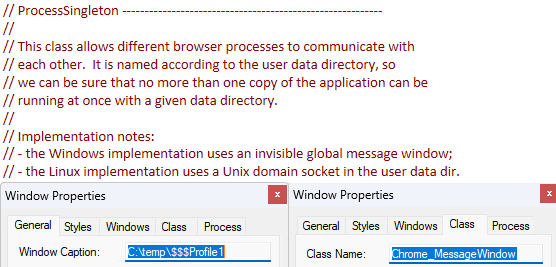

- The original 2008 release of the Chrome browser was very limited in terms of features, as the team was heavily focused on performance, security, and simplicity. But one feature that seemed to get a lot of consideration early on was support for Mouse Gestures; some folks on the team loved gestures, but there was recognition that it was unlikely to be a broadly-used feature. Ultimately, the Chrome team decided not to implement mouse gestures, instead leaving the problem space to browser extensions.

Years later, after Chrome became my primary browser, I lost my beloved IE Mouse Gestures extension, so I started hunting for a replacement. I found one that seemed to work okay, but because I run Fiddler constantly, I soon noticed that every time I invoked a gesture, it sent the current page’s URL and other sensitive data off to some server in China. Appalled at the hidden impact to my privacy and security, I reported the extension to the Chrome Web Store team and uninstalled it. The extension was delisted from the web store.

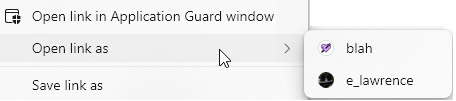

Some time later, now back on the Edge team, a new lead joined and excitedly recommended we all try out a great Mouse Gestures extension for Chromium. I was disappointed to discover it was the same extension that had been removed previously, now with a slightly more complete Privacy Policy, and now using HTTPS when leaking users’ URLs to its own servers. (Update: As of 2023, Edge has built-in Mouse Gestures. Hooray!)

With these background stories in hand, let’s look at the tradeoffs.

“Bloated!”

There are three common classes of complaint from folks who point at the long list of features Edge has added over upstream Chromium and furiously charge “It’s bloated!“:

- User Experience complexity

- Security/reliability

- Performance

UX Complexity

Usually when you add a feature to the browser, you add new menu items, hotkeys, support articles, group policies, and other user-visible infrastructure to support that feature. If you’re not careful, it’s easy to accidentally break a user’s longstanding workflows or muscle memory.

One of the Windows 7 Design Principles was “Change is bad, unless it’s great!” and that’s a great truth to keep in mind– entropy accumulates, and if you’re not careful, you can easily make the product worse. Users don’t like it when you move their cheese.

A natural response to this concern is to design new features to be unobtrusive, by leaving them off-by-default, or hiding them away in context menus, or otherwise keeping them out of the way. But now we’ve got a problem– if users don’t even know about your feature, why bother building it? If potential customers don’t know that your unique and valuable features exist, why would they start using your product instead of sticking with the market leader, even if that leader has been stagnant for years?

Worse still, many startups and experiments are essentially “graded” based on the number of monthly or daily active users (MAU or DAU)– if a feature isn’t getting used, it gets axed or deprioritized, and the team behind it is reallocated to a more promising area. Users cannot use a feature if they haven’t discovered it. As a consequence, in an organization that lacks powerful oversight there’s a serious risk of tragedy, whereby your product becomes a sea of banners and popups each begging the user for attention. Users don’t like it when they think you’re distracting them from the cheese they’ve been enjoying.

Security/reliability risk

Engineers and enthusiasts know that software is, inescapably, never free of errors, and intuitively it seems that every additional line of code in a product is another potential source of crashes or security vulnerabilities.

If software has an average of, say, two errors per thousand lines of code, adding a million lines of new feature code mathmatically suggests there are now two thousand more bugs that the user might suffer.

If users have to “pay” for features they’re not using, this feels like a bad deal.

Performance

Unlike features, Performance is one of the “Universal Goods” in software– no user anywhere has ever complained that “My app runs too fast!” (with the possible exception of today’s gamers trying to use their 4ghz CPUs to run retro games from the 1990s).

However, we users also note that, even as our hardware has gotten thousands of times faster over the decades, our software doesn’t seem to have gotten much faster at all. Much like our worry about new features introducing code defects, we also worry that introducing new features will make the product as a whole slower, with higher CPU, memory, or storage requirements.

Each of these three buckets of concerns is important; keep them in mind as we consider the other side.

“Batteries Included!“

We use software to accomplish tasks, and features are the mechanism that software exposes to help us accomplish our tasks.

We might imagine that ideal software would offer exactly and only the features we need, but this is impractical. Oftentimes, we may not recognize the full scope of our own needs, and even if we do, most software must appeal to broad audiences to be viable (e.g. the “10% of Microsoft Office” problem). And beyond that, our needs often change over time, such that we no longer need some features but do need other features we didn’t use previously.

One school of thought suggests that the product team should build a very lightweight app with very few features, each of which is used by almost everyone. Features that will be used by fewer users are instead relegated to implementation via an extensibility model, and users can cobble together their own perfect app atop the base.

There’s a lot of appeal in such a system– with less code running, surely the product must be more secure, more performant, more reliable, and less complex. Right?

Unfortunately, that’s not necessarily the case. Extension models are extremely hard to get right, because until you build all of the extensions, you’re not sure that the model is correct or complete. If you need to change the model, you may need to change all of the extensions (e.g. witness the painful transition from Chromium’s Manifest v2 to Manifest v3).

Building features atop an extension model sometimes entails major performance bugs, because data must flow through more layers and interfaces, and if needed events aren’t exposed, you may need to poll for updates. Individual extensions with common needs may have to do redundant work (e.g. each extension scanning the full text of each loaded page, rather than the browser itself scanning the whole thing just once).

As we saw with the Mouse Gestures story above, allowing third-party extensions carries along with it a huge amount of complexity related to security risk and misaligned incentives. In an adversarial ecosystem where good and bad actors both participate, you must invest heavily in security and anti-abuse mechanisms.

Finally, regression testing and prevention gets much more challenging when important features are relegated to extensions. Product changes that break extensions won’t block the commit queue, and the combinatorics involved in testing with arbitrary combinations of extensions quickly hockey sticks upward to infinity.

Extensions also introduce complexity in the management and update experience, and users might miss out on great functionality because they never discovered extension exists to address a need they have (or didn’t even realize they have). You’d probably be surprised by the low percentage of users that have any browser extensions installed at all.

With Fiddler, I originally took the “Platform” approach where each extra feature was its own extension. Users would download Fiddler, then download four or five other packages after/if they realized such valuable functionality existed. Over time, I realized that nobody was happy with my Ikea-style assemble-your-own debugger, so I started shipping a “Mondo build” of Fiddler that just included everything.

Extensions, while useful, are no panacea.

Principles

These days, I’ve come around to the idea that we should include as many awesome features as we can, but we should follow some key principles:

- To the extent possible, features must be “pay to play.” If a user isn’t using a given feature, it should not impact performance, security, or reliability. Even small regressions quickly add up.

- Don’t abuse integration to avoid clean layering and architecture. Just because your feature’s implementation can go poke down into the bowels of the engine doesn’t mean it should.

- Respect users and carefully manage UX complexity. Remember, “change is bad unless it’s great.” Invest in systems that enable you to only advertise new features to the right users at the right time.

- Remove failed experiments. If you ship a feature and find that it’s not meeting your goals, pull it out. If you must accommodate a niche audience that fell in love, consider whether an extension might meet their needs.

- Find ways to measure, market, and prioritize investments in Fundamentals. Features usually hog all the glory, but Fundamentals ensure those features have the opportunity to shine.

-Eric