For Christmas 2020, I was home alone. The highlight of my day was discovering that Jack in the Box was open. I enjoyed my Christmas cheeseburger dinner at a picnic table in a park down the street.

Unexpectedly, my Christmas plans fell through for 2021, and I faced a repeat of 2020. But making Jack in the Box a holiday tradition seemed a bit more grim than I was ready to accept, so I started hunting for other options with just five days left to go.

I’d recently finished booking a family holiday cruise for New Years 2023, and I idly wondered whether there were any cheap last-minute cruises out of Galveston this holiday that would work with my schedule. And, sure enough, Royal Caribbean had one leaving on Christmas Eve for relatively cheap (~3x their cheapest off-season rate).

So, that seemed like a definite possibility. I love cruising (no internet, under five minute walk to every meal and show), even if I lament the ecological impact and cringe at the economic inequality– rich tourists served by crews from poor countries, taking excursions in beautiful but impoverished areas. (Improving environmental impact mostly awaits better technology, but I believe the best approach for addressing the economic inequality isn’t in abstaining but instead tipping as heavily as you can afford.)

Still… could going on a cruise “alone” (with thousands of strangers) really be a good idea??

Over the last decade I’ve concluded that I am not, in fact, the introvert I’d always considered myself (thinking back to how as a grade schooler I was too shy to even ask for ketchup in McDonalds), but I am certainly not a social butterfly either. Beyond my normal anxiety about being out of my comfort zone, this trip promised to be one of BIG FEELINGS… After all, I did get engaged on a cruise1 and on this cruise I’d be bringing along the final paperwork for my imminent divorce. So, yeah. Weighty.

But after a moment pondering a Christmas whose highlight otherwise would be finishing my binge-rewatch of Friday Night Lights (apparently, I’m a cliche), I decided almost anything would be better and booked the trip. I went through CostCo Travel (same prices as direct, and they send you a $140 gift card after returning) and booking for one was remarkably straightforward. (It was hard to overlook the fact that inviting a cabinmate would cost nearly nothing extra, but doing that wasn’t in the cards.)

I wavered a bit about whether to splurge on a balcony, a luxury I’d never enjoyed before, and ultimately decided “What the heck, it’s Christmas!”

On December 22nd, I realized that beyond full-vaccination, the cruise line also requires a negative COVID test dated within two days of the cruise. Alarmingly, I couldn’t find anywhere in Austin willing to do a test in the next five days. But fortunately the cruise terminal itself offered “testing of last resort” and there were still hundreds of testing slots open. So that was sorted.

I spent most of December 23rd shopping for clothing for the trip– I haven’t worn anything remotely formal in close to two years, and unfortunately most of my “fancy” pants no longer fit. In the course of packing, I realized I no longer owned a suit/garment bag (lost either in the move to Texas ages ago, or buried in my soon-to-be-ex’s house) so I spent a fair bit of time hunting for a new one. All of the options were expensive (~$150-$300) and most had terrible reviews on Amazon. After checking online and two malls in person, I swung by Goodwill and snagged an old red Samsonite in aged but workable condition for the princely sum of $11.

I procrastinated on finishing packing until late Thursday night, and set off for the four-hour drive to Galveston on Friday morning. It was a bit nerve-wracking to realize that if I had any sort of car trouble, I was going to miss the entire trip without a chance of a refund, and if I got to the terminal but failed the COVID test I was going to have to get back in the car and drive straight back to Austin. These thoughts occupied my mind for the first few hours of the drive.

I told myself that at least this situation couldn’t be as bad last year. On 12/23/2020, I’d set off on a quixotic last second seven-hour drive to visit a friend. Only upon arrival at the hotel did I realize that I’d left my well-packed suitcase behind atop my library sofa at my house in Austin. It was after 9PM on Christmas Eve Eve, 40F and windy out, and I had nothing to wear but basketball shorts and a light t-shirt. Adventure, amirite?

I chuckled at how dumb last year’s situation was until I abruptly realized with bemused horror that, while I had carefully ensured that all three pieces of luggage (garment bag, suitcase, daybag) were in my car, I’d never actually gotten around to putting my dress shirts into the garment bag. Fortunately, I had an hour to spare, and a Kohl’s outside of Houston got me sorted out in half that.

Fortunately, my COVID rapid test at the terminal turned out negative.

Repeatedly throughout the check-in and boarding process folks would ask “How many in your party?” and I would sheepishly respond “one,” but I soon felt a lot better about it because the universal reaction was summed up in the response I got from the first person helping me: “Great, you’ll be easy then.”

Shortly after 1pm I was aboard. I explored the ship a bit while waiting for the staterooms to be released; I gawked at the massive three-story Christmas tree on the Deck 4 promenade.

At 2pm, we got the notification that our rooms were ready, and I headed to mine. I eagerly awaited the arrival of my luggage, as it wasn’t among the bags lining the hallway.

And I waited. And waited. With mounting dismay I pondered spending the entire cruise in just the workout clothes I wore for the drive. “I really need to stop travelling in such shabby stuff” I berated myself. I went out to continue exploring the ship, checking back at my stateroom periodically. One of my favorite discoveries was the peek-a-boo view down into the bridge:

I hadn’t eaten yet all day, and at 4:30 I headed to the Windjammer restaurant to grab a bite only to realize that it had closed at 4pm; the old saw “You’ll never be hungry on a cruise ship” turns out not to be entirely accurate. Unlike Disney, the top deck doesn’t have small stands offering light fare all day; only small soft-serve ice cream cones were available2. I had two and enjoyed the beautiful weather and cool breeze on the deck.

Fortunately, at 5pm my main suitcase arrived and my stress level dropped considerably. It didn’t have my fanciest clothing, but I would be okay.

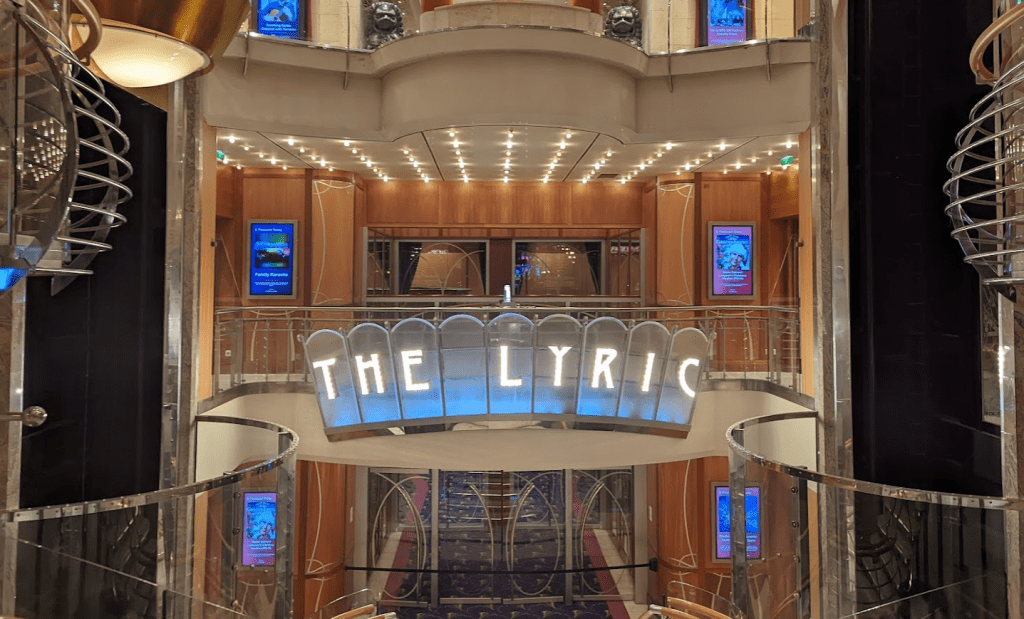

I headed to the “Welcome Aboard” show in the Lyric Theater at 7pm– the Cruise Director opened by asking the audience the usual questions: “How many of you are celebrating a birthday? A honeymoon? An anniversary?” with the expected jokes about the sparse attendance of honeymooners (“They’re busy in their rooms, I suspect”) and muted enthusiasm of the anniversary celebrators (“They’re a lot less excited than the honeymooners”). She finally joked “How many of you are celebrating a divorce?” and I couldn’t help but hoot and raise my now mostly-empty glass, the Old Fashioned it formerly contained now lightening my mood. There was a bit of laughter in the audience as she quipped “Well, y’all know where to find him this whole trip, up in the Blue Moon club” while miming a disco dance routine.

After the tame but amusing comedy show (Jackson Perdue), I went to dinner (I’d picked the “My Time” dining option, which turned out to mean “Pick from any of the few extra-late dinner slots”) and had a delicious braised beef dish at a quiet, out of the way table. As with the other staff before him, my waiter seemed happy about the relative ease of dealing with a solo traveler.

After dinner, I got back to my room and happily discovered that my garment bag had made it. Phew. I spent another hour or so exploring the ship, before heading to the “Solo Travellers” meetup at the aforementioned club. It was odd scene, to put it mildly– there were some late 30s guys milling about, and a handful of early 20s women who were travelling with their families but had aged out of the ship’s Teens club.

I nursed a drink while people-watching; after a while, a social butterfly (an Israeli immigrant CS professor at a Texas university) started pulling people together and introducing everyone to the folks he’d chatted with thus far. At one point, he asked if I was “on the prowl” and I almost giggled at the thought, but I just gestured at the kids around us and said “No.” He replied “Well, if you change your mind and need a wingman, I’m here.” I ended up drinking and chatting with him and another Israeli transplant (a real-estate agent from Chicago) until around midnight.

The next morning, Christmas, I woke up and headed upstairs for a picture-perfect breakfast:

…and finished my coffee on my balcony, enjoying the screensaver-perfect weather:

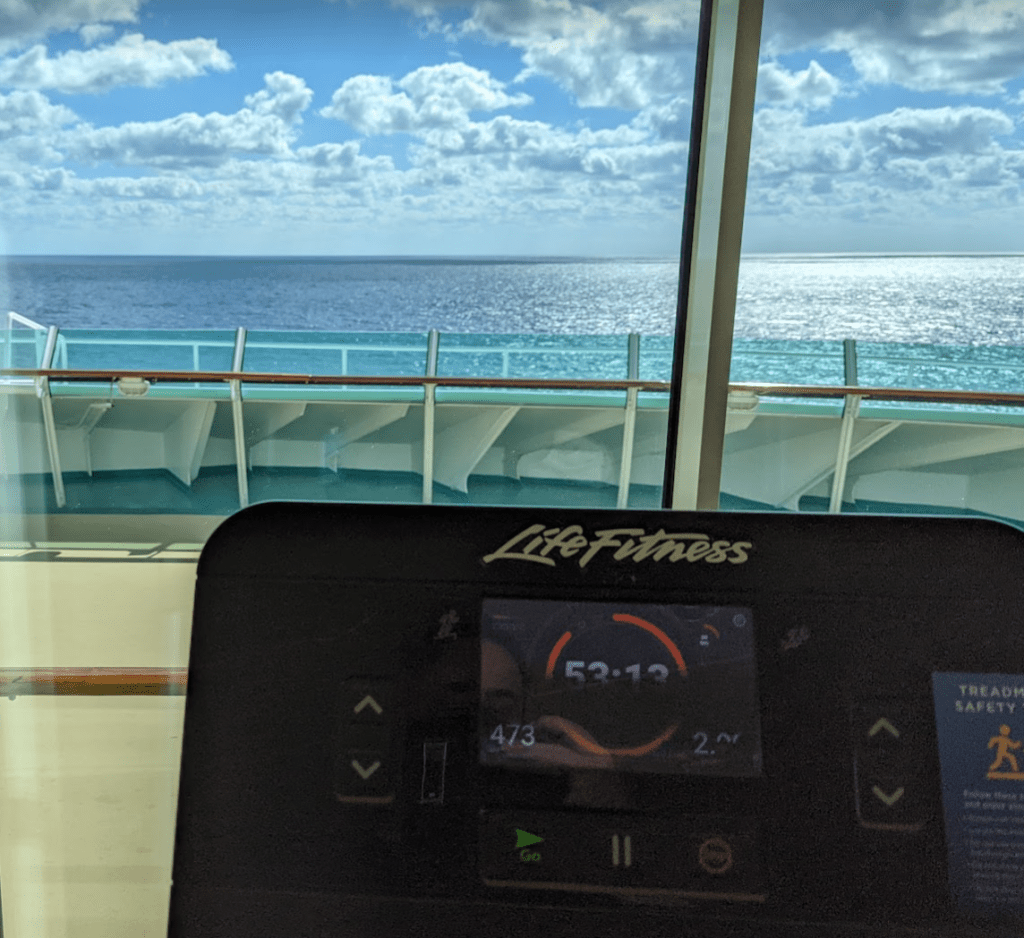

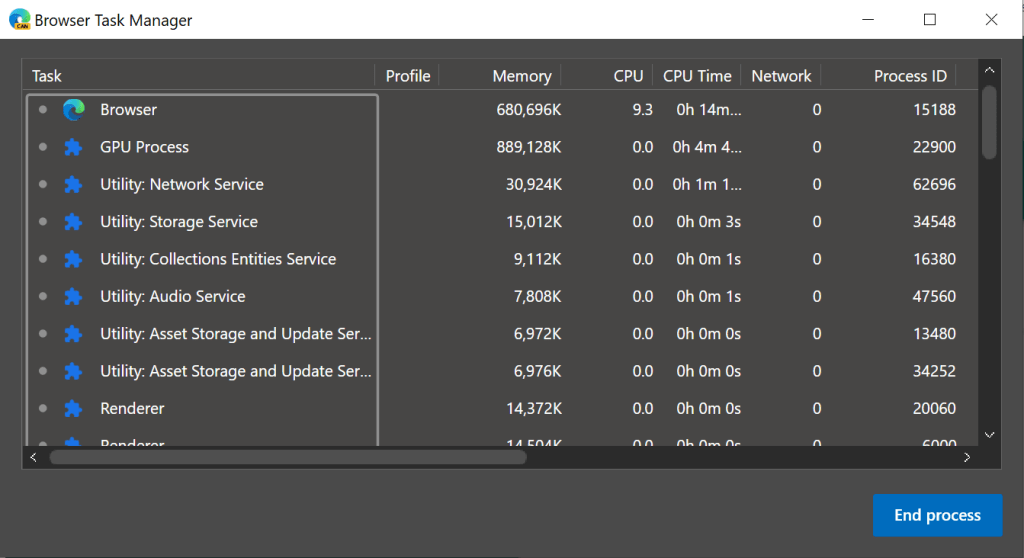

At eleven, I headed up to the ship’s fitness center. Lamely, they’d disabled the water dispenser, suggesting that exercisers head to the nearest bar to ask for water (Two years in, people, we know that COVID is airborne and water-fountains aren’t the problem!) but other than that, the gym was nice. I spent a bit over an hour on a treadmill at the bow, sweating my way across the Gulf.

Wearing a mask while working out wasn’t very pleasant, but not as bad as I’d feared, and I have some ambitious fitness goals for the coming year and reminded myself that I needed to start getting less comfortable if I’m to achieve them.

After the gym, I spent a half hour walking the track on deck in the strong breeze to cool down…

…then grabbed a quick shower in my stateroom and headed to lunch. One of the Israelis from the night before invited me to join him and his family and after mild protestations I gratefully did so. We had a great lunch; his six year old delighted in my Dad jokes that my own kids no longer appreciate. They’d apparently missed their original cruise (a seven-night cruise that had left a few days before) because they’d taken their pre-trip COVID tests a day too early (!!!).

I putzed around all afternoon, opened a bottle of wine, left a holiday/thank you card for the cabin steward, put on a fancy shirt and slacks, and headed to dinner.

After dinner, I wandered around topside for hours, enjoying the perfect breeze and night sky.

I finished reading my book and fell asleep around midnight. It was an almost perfect day.

The next two days were slated for adventure.

We arrived at Puerto Costa Maya around noon on December 26th under perfect skies.

I’d booked a “Chill River Rafting” excursion, which involved a longish (90 minutes) van ride out to a ranch where we put on life jackets and boarded rafts in groups of 4 to 6. The activity was described as “Activity Level: Moderate” which most of us took to mean that it wasn’t going to be white-water rafting, but it would at least involve some paddling. Alas, it did not; it was more akin to a gondola ride in Venice, with a guide pushing the raft down the smooth river with a long pole. My seatmate (a ripped senior majoring in history at Kansas State and sporting massive tattoos) and I chatted and snarked at the tameness of our river “adventure.” I was a bit disappointed that I hadn’t brought my phone because I was afraid of losing it in rough waters. Lol.

We rode the small river about half a mile through the jungle, past a public park where the locals snorted and called out to their swimming kids in Spanish “Look, the Americans are afraid of the water”. To be fair, we did look a bit ridiculous. We mused about whether the rafting company was paying for access to the river and concluded “Naw, but they sell tickets to the locals to see the Americans in the Zoo.”

Eventually, we reached a small lagoon where we were offered a glass of sparkling wine and a thirty-minute break for swimming. Most of us doffed our wildly unnecessary life jackets and got down into the water (it wasn’t too cold) and swam around a bit. One couple remained on their raft; I suspect they were newly engaged. Most of us were dressed in swimsuits and other athletic wear, but they looked like they’d just stepped out of central casting for a 40s movie– her with bright red lips and him in an Irish flat cap; both were wearing clothes and hairstyles that could’ve easily been of that era. I suddenly wondered whether they were famous– the last time I’d encountered some suspiciously attractive people, I much later learned that they were super famous. I almost swam over to talk to them, but decided I had no business bothering them. I idly spent the rest of the cruise elaborating an imagined backstory about how this anachronistic couple ended up on our ship.

With our swimming break over, we headed back to our departure point for sandwiches and Pepsi before getting back in the van for the long ride back to the ship. It was a relaxing and pleasant excursion, but definitely not what I’d expected.

Back on the boat, I showered and went topside to enjoy the weather. The Cowboys vs. Washington Football team game was on the big screen and I watched my family’s favorite team get absolutely demolished by Texas while I sipped a discounted Mai Tai (the drink of the day).

Dinner was Beef Stroganoff which was prepared much differently than I’d had as a kid– it was really good. After dinner, I went to the late (10:15) song and dance show featuring Bobby Brooks Wilson, son of Jackie Wilson, a famous performer of the early 50s to 70s.

Sadly, the show was sparsely attended, but we cheered louder than our numbers would have predicted for his flamboyant performance of music of his father’s era. The final song was by Bruno Mars, a bandmate of Bobby’s decades ago when Wilson was in the Navy stationed in Hawaii. After the show, I tried to get to bed before midnight because I had a 6:15am wakeup for the next day’s excursion.

The next morning we arrived on the island of Cozumel, but my excursion group wasn’t staying– We immediately boarded a ferry for a 20 minute ride to the mainland. It was a pleasant ride although much rockier than on the dramatically larger cruise ship. Seated topside, I only found out later that some folks below deck were puking their guts out.

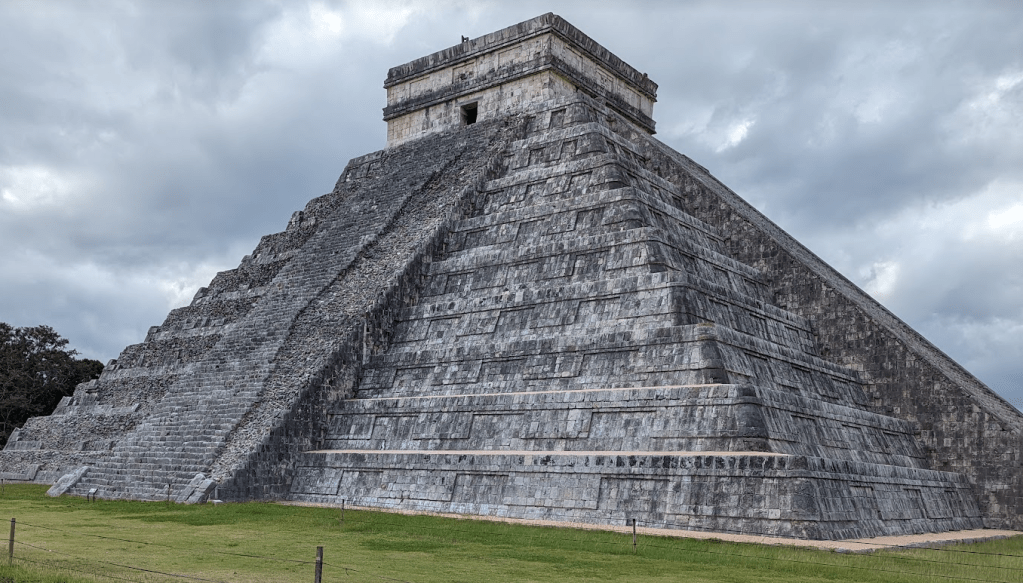

We then had a very long van ride (over two hours) out to the Chichen Itza ruins, but it was made more pleasant by an hour-long lecture by our guide about the history of the Mayan city.

When we finally arrived, the entry was extremely crowded (but apparently much less crowded than the prior day) but once we got out to the ruins, everyone was able to spread out.

The pyramid was really impressive, and I was astonished that the chirping bird echo really happens. Very cool. We also spent a lot of time talking about the various symbolic aspects of the pyramid (its serpents light up on the equinox, there are 91 steps on each side, and 1 on top for a total of 365, etc).

Given our time constraints, we weren’t supposed to have any time for souvenir shopping (vendors ringed the site, and some of their wares were pretty cool looking) but I quickly overpaid $20 for a cool lucite pyramid:

… on the walk from the temple over to the Great Ball Court.

Victors of the game won the honor of being beheaded as human sacrifices.

We finished our hour-long tour and headed back to the van for the long drive back to the ferry. On the ferry, tired travellers napped; I almost drowned in nostalgia at the sight of a 3yo boy sleeping on his dad’s chest, and the lovebird time travellers from the 1940s dozed nuzzled into each other on the next bench.

Back on the boat, I enjoyed the sunset with a Mai Tai.

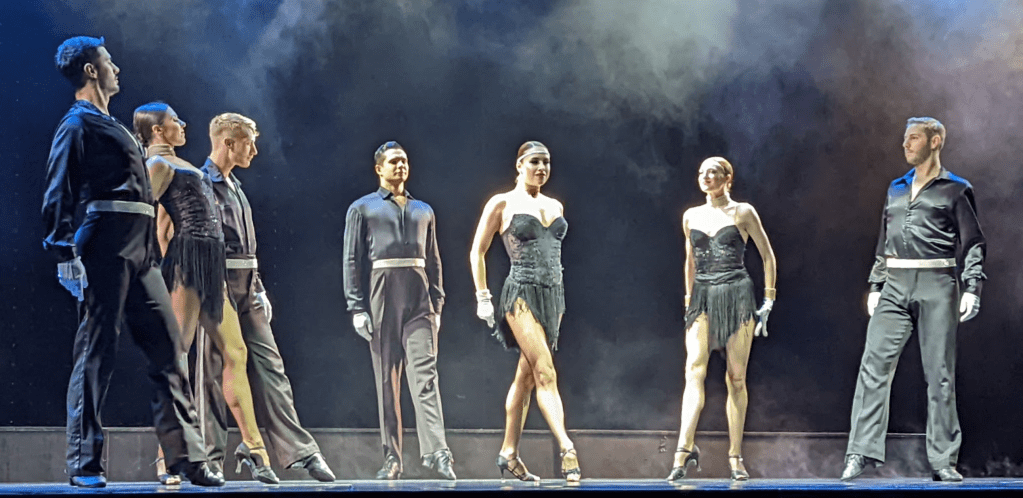

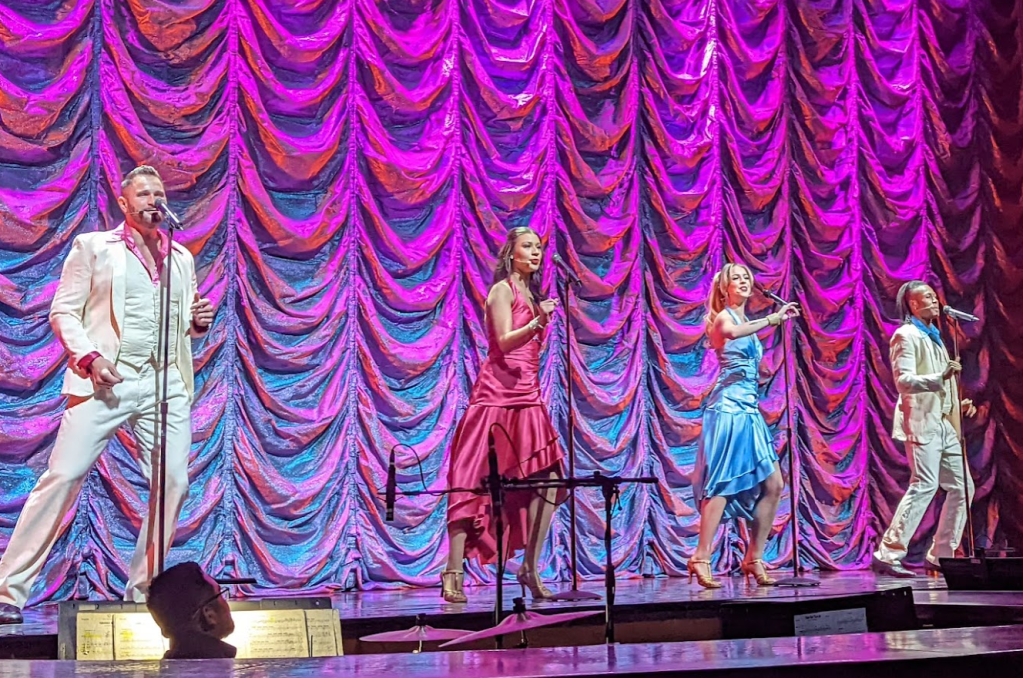

Before dinner, I headed to the “Invitation to Dance” song and dance show, and was amazed at the rapid fire spectacle of back-to-back numbers (some of the costume changes must’ve taken under fifteen seconds). It was a really impressive performance. I’ve always loved live performances of almost every form (plays > music > magic > comedy > opera > ballet) and while I don’t think I’d ever just randomly go downtown to see a song and dance show, I was incredibly glad that I didn’t miss this one. As with all of the shows I saw on the ship, I easily got second-row seats (the front row was closed off in a nod to social distancing).

After dinner, I went back topside to enjoy the night air. Because there are few lights above the front of the ship, the view of the night sky from the helipad on Deck Five Forward was amazing. I spent an hour looking skyward as a cool breeze blew over the deck. It’s hard to capture the majesty of the sky, even with the Pixel 6’s cool “Night Sight” mode:

I’ve never thought of myself as a city boy, but in a world rife with light pollution, it’s notable that I can think of almost every time I could see the stars reaching all the way down to the horizon. In the summer of 1991 after Grade 6, laying out on a lakeside dock in Michigan with my “girlfriend”3; in 1996 in rural Minnesota, driving cross-country with my friend Anson; in February 2010, the night before my wedding in a beachside hot tub with our friends. And now, December 2021, sailing across the Gulf of Mexico.

After my stargazing, I went to Jackson Perdue’s “Adult” comedy show, which was much funnier than his tame opening night all-ages show; this was more like the standup I’m used to from Netflix specials and the like.

The show was followed by a disappointing announcement from the cruise director that the Ice Show I’d booked for the following day (there’s a full ice skating rink on-board) had been canceled due to technical problems. Nevertheless, I went to bed looking forward to another relaxing day at sea as we headed back to Galveston.

In the morning, I had breakfast and headed to the gym, determined to push myself. After over an hour on the treadmill, I walked another two miles or so on the deck, happily enjoying the breeze as sweat poured everywhere.

I ended up sore for the rest of the trip. Ah well. A Pina Colada helped.

That night, I packed my bags before heading to my usual dining room for appetizers only (eating far too much) before a late dinner at the on-ship steakhouse (yummy, but probably not worth the upcharge).

The Farewell show’s comedian was Cary Long (whose act appears to be pretty standard, with a bunch of word-for-word overlap with this YouTube video from eight years ago), but he did one pretty impressive trick– he spent five minutes of the act greeting folks (and chatting briefly) in their native languages (apparently, there were speakers of over 30 languages aboard). Not comedy perhaps, but it was very cool to see.

The next morning, we docked in Galveston and I reluctantly turned cell service back on (and was promptly flooded with messages). After a quick breakfast at the Windjammer buffet, it was time to leave the ship for the long drive back to Austin.

All in all, the trip went better than I dreamed.

Happy New Year, y’all. May 2022 bring you great things!

-Eric

1 A seven-night Carnival cruise from Rome around the Mediterranean, paid for by Fiddler’s Engineering Excellence Award; a $5000 expense account accompanied the glass trophy.

2 It wasn’t until the very last evening of the cruise that I realized that the coffeeshop on Deck 5 midship offers free pizza all day.

3 Amy H. asked me to be her boyfriend. I had no particular feelings for her, but I said “sure” because I was twelve and what else are you supposed to do?

Thirty years later, I still remember my feeling of wonder that night out on the dock– “I’ve never felt this way before. Is this love after all?” In the cold light of morning I realized, “Nope, that was the beginnings of hypothermia.”