Note: This blog post was originally written before the new Chromium-based Microsoft Edge was announced. As a consequence, it includes discussion of the behavior of the Legacy Microsoft Edge browser. The new Chromium-based Edge behaves largely the same way as Google Chrome.

Last Update: 13 June 2025

InPrivate Mode was introduced in Internet Explorer 8 with the goal of helping users improve their privacy against both local and remote threats. Safari introduced a privacy mode in 2005.

All leading browsers offer a “Private Mode” and they all behave in the same general ways.

Privacy Mode Behaviors

HTTP Caching

While in Private mode, browsers typically ignore any previously cached resources and cookies. Similarly, the Private mode browser does not preserve any cached resources beyond the end of the browser session. These features help prevent a revisited website from trivially identifying a returning user (e.g. if the user’s identity were cached in a cookie or JSON file on the client) and help prevent “traces” that might be seen by a later user of the device.

In Firefox’s and Chrome’s Private modes, a memory-backed cache container is used for the HTTP cache, and its memory is simply freed when the browser session ends. Unfortunately, WinINET never implemented a memory cache, so in Internet Explorer InPrivate sessions, data is cached in a special WinINET cache partition on disk which is “cleaned up” when the InPrivate session ends.

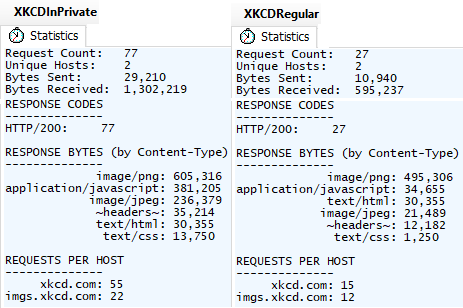

Because this cleanup process may be unreliable, in 2017, Edge Legacy made a change to simply disable the cache while running InPrivate, a design decision with significant impact on the browser’s network utilization and performance. For instance, consider the scenario of loading an image gallery that shows one large picture per page and clicking “Next” ten times:

Because the gallery reuses some CSS, JavaScript, and images across pages, disabling the HTTP cache means that these resources must be re-downloaded on every navigation, resulting in 50 additional requests and a 118% increase in bytes downloaded for those eleven pages. Sites that reuse even more resources across pages will be more significantly impacted.

Another interesting quirk of Edge Legacy’s InPrivate implementation is that the browser will not download FavIcons while InPrivate. Surprisingly (and likely accidentally), the suppression of FavIcon downloads also occurs in any non-InPrivate windows so long as any InPrivate window is open on the system.

Web Platform Storage

Akin to the HTTP caching and cookie behaviors, browsers running in Private mode must restrict access to HTTP storage (e.g. HTML5 localStorage, ServiceWorker/CacheAPI, IndexedDB) to help prevent association/identification of the user and to avoid leaving traces behind locally. In some browsers and scenarios, storage mechanisms are simply set to an “ephemeral partition” while in others the DOM APIs providing access to storage are simply configured to return “Access Denied” errors.

You can explore the behavior of various storage mechanisms by loading this test page in Private mode and comparing to the behavior in non-Private mode.

Within IE and Edge Legacy’s InPrivate mode, localStorage uses an in-memory store that behaves exactly like the sessionStorage feature. This means that InPrivate’s storage is (incorrectly) not shared between tabs, even tabs in the same browser instance.

Update: Some browsers offer the option (opt-in or opt-out) to disable third-party cookies entirely while running in Private Mode, like this toggle on Chrome’s Incognito new tab page:

Similarly, Edge’s InPrivate mode offers a toggle to use the Strict Mode of the Tracking Prevention feature:

Network Features

Beyond the typical Web Storage scenarios, browser’s Private Modes should also undertake efforts to prevent association of users’ Private instance traffic with non-Private instance traffic. Impacted features here include anything that has a component that behaves “like a cookie” including TLS Session Tickets, TLS Resumption, HSTS directives, TCP Fast Open, Token Binding, ChannelID, and the like.

As of June 2024, Chromium-based browsers now default to enabling HTTPS First mode (automatic upgrades from HTTP to HTTPS URLs, if possible) in Private Mode.

Automatic Authentication

In Private mode, a browser’s AutoComplete features should be set to manual-fill mode to prevent a “NameTag” vulnerability, whereby a site can simply read an auto-filled username field to identify a returning user.

On Windows, most browsers support silent and automatic authentication using the current user’s Windows login credentials and either the NTLM and Kerberos schemes. Typically, browsers are only willing to automatically authenticate to sites on “the Intranet“. Some browsers behave differently when in Private mode, preventing silent authentication and forcing the user to manually enter or confirm an authentication request:

- In Edge InPrivate, Edge Legacy’s InPrivate, and Firefox Private Mode, the browser will not automatically respond to a HTTP/401 challenge for Negotiate/NTLM credentials.

- In IE InPrivate and Chrome/Brave Incognito (prior to v81), the browser will automatically respond to a HTTP/401 challenge for Negotiate/NTLM credentials.

Notes:

- In Edge Legacy and the new Chromium-based Edge, the security manager returns MustPrompt when queried for URLACTION_CREDENTIALS_USE.

- Unfortunately Edge Legacy’s Kiosk mode runs InPrivate, meaning you cannot easily use Kiosk mode to implement a display that projects a dashboard or other authenticated data on your Intranet.

- For Firefox to support automatic authentication at all, the

network.negotiate-auth.allow-non-fqdnand/ornetwork.automatic-ntlm-auth.allow-non-fqdnpreferences must be adjusted.

Accept-Language

In one of the clearest privacy/user-experience tradeoffs, Chromium now sends only the first Accept-Language rather than the full list when loading sites in Private Mode.

registerProtocolHandler

All common browsers block the HTML5 registerProtocolHandler API in private mode.

System Integrations

Browsers often will change their behavior for windows running in Private Mode when integrating with the operating system. These restrictions are intended to help prevent inadvertent disclosure or retention of Private Mode information outside of the Private Mode browser instance.

For example, some browsers will avoid handing thumbnails of Private Mode windows to the OS, which uses such thumbnails for task switching UI, history views, etc.

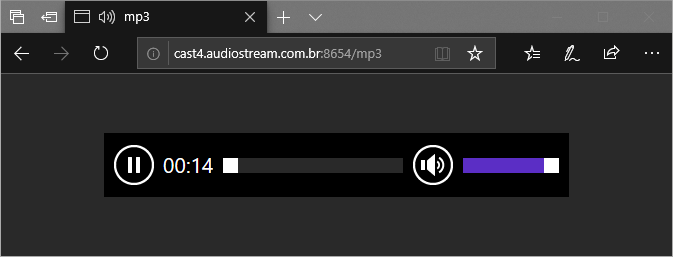

Similarly, Chromium intends to stop exposing media titles and thumbnails to the OS from Private Mode pages to avoid their display in the volume mixer, playback controls on the OS lock screen, etc.

On Android, the Edge Private Mode sets the flag to prevent screen captures (user-initiated or app-invoked) from capturing the image of the screen (which users may like, or may find annoying). While Windows exposes the SetWindowDisplayAffinity() API, that API is presently used only by DRM and not by Private Mode.

As of 2024, Chromium will flag data copied from an Incognito window to the clipboard as “Private” so that it does not go in Clipboard history or Windows’ Clipboard cloud sync.

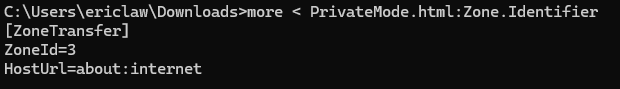

When downloaded and SaveAs files are saved to disk, the Mark-of-the-Web has the original URLs removed and replaced with the generic about:internet:

Another concern surrounds invocation of other applications (e.g. via an AppProtocol) that could allow web content running in a private mode instance to trigger an app that would in turn make a request outside of InPrivate allowing user identification via, for example, that app’s automatic release of credentials. (Example)

Detection of Privacy Modes

While browsers generally do not try to advertise to websites that they are running inside Private modes, it can be relatively straightforward for a website to feature-detect this mode and behave differently. For instance, some websites like the Boston Globe block visitors in Private Mode (forcing login) because they want to avoid circumvention of their “Non-logged-in users may only view three free articles per month” paywall logic.

Sites can detect privacy modes by looking for the behavioral changes that signal that a given browser is running in Private mode; for instance, indexedDB is disabled in Edge Legacy while InPrivate. Detectors have been built for each browser and wrapped in JavaScript libraries. Defeating Private mode detectors requires significant investment on the part of browsers (e.g. “implement an ephemeral mode for indexedDB“) and fixes lagged until mainstream news sites (e.g. Boston Globe, New York Times) began using these detectors more broadly.

See also:

- Stack Overflow topic

- Mozilla indexedDB issue

- Inferring Incognito from web-accessible extension surface

- FavIcon partitioning

End users might successfully circumvent such checks using a manually-created “Ephemeral Profile”, a regular mode profile which is configured to delete all storage on exit.

Signaling Privacy Mode

Update: Perhaps surprisingly, the new Microsoft Edge sends a deliberate signal to (only) the user’s default search engine when it is loaded in InPrivate mode. The HTTPS request header PreferAnonymous: 1 is sent on requests to the server to allow it to avoid caching any data related to the user’s use of the search engine.

This header is sent only to the search engine, and not to other sites.

“Guest” Profile

Browsers based on Chromium often also have a Guest Browsing mode, which has a superset (mostly*) of Private Mode behavior.

When you “Browse as Guest”, the browser session treats itself as running in Private Mode, but unlike a normal Private Mode session, the session also starts with an empty user profile. That means the browser will not

- show history entries in the address box or History page

- list your bookmarks

- offer to fill in your account information or passwords

- offer to fill in autocomplete information

- etc.

When you close all Guest Profile windows, your history and other state generated in the session is deleted, just like in regular Private mode.

Using a Guest Profile helps prevent you from accidentally leaking information to sites (e.g. inadvertently triggering an autofill).

* Internally to Chromium, most features check a boolean flag IsOffTheRecord() when deciding how to behave. This boolean returns true for both InPrivate/Incognito and Guest profiles. In rare cases, Guest is not designed to have InPrivate behavior. For instance, as of Edge 86, the PreferAnonymous header mentioned earlier is not sent for Guest profiles. Developers can distinguish InPrivate/Incognito from Guest like so:

Profile::FromBrowserContext(web_contents->GetBrowserContext())

->IsIncognitoProfile());Advanced Private Modes

Generally, mainstream browsers have taken a middle ground in their privacy features, trading off some performance and some convenience for improved privacy. Users who are very concerned about maintaining privacy from a wider variety of threat actors need to take additional steps, like running their browser in a discardable Virtual Machine behind an anonymizing VPN/Proxy service, disabling JavaScript entirely, etc.

The Brave Browser offers a “Private Window with Tor” feature that routes traffic over the Tor anonymizing network; for many users this might be a more practical choice than the highly privacy-preserving Tor Browser Bundle, which offers additional options like built-in NoScript support to help protect privacy.

Common Questions

Q: When I open a new InPrivate window, somehow I’m already signed in to some site I was previously using InPrivate. What gives?

A: Today, Chromium uses a single “browser session” for all Private Mode windows. See this post for discussion.

Q: From web content, can I create a link that automatically opens InPrivate? Something like <a href="http://secret.example.com" rel="private" />?

A: No. There’s presently no standard for this, and browsers cannot safely implement something like this until the browser supports multiple parallel web sessions for Private mode. Otherwise, website running outside of Private Mode could “push” an identifier into a running Private Mode session that would unmask the user.

Q: As an end-user, can I configure a given site to always open in Private mode?

A: Not yet. You can easily create a desktop shortcut that does so (just add the --inprivate command line flag), but that won’t impact navigations from the address bar or regular site-to-site links inside the browser. The Issue mentions another workaround. But it would be a cool feature to build in, right?

Related Links

- https://www.blaseur.com/papers/www18privatebrowsing.pdf

- https://elie.net/blog/privacy/understanding-how-people-use-private-browsing/

- https://www.consumerreports.org/internet/incognito-mode-web-browser-what-it-really-does/

- https://support.mozilla.org/en-US/kb/common-myths-about-private-browsing

- Safari Private Browsing 2.0

-Eric