Way back on May 11th of 2022, I was visiting my team (Edge browser) for the week in Redmond, Washington. On Wednesday night, I left my ThinkPad X1 Extreme laptop in a work area on the 4th floor of the office when I went out for drinks with friends.

After dinner, I decided not to head back to the office to grab my laptop and bag to bring them back to the hotel. When I arrived at the office the next morning, my backpack (containing $80 in cash) and charger were still there, but my laptop was nowhere to be found. An exterior door in a nearby stairwell had been failing to latch but hadn’t been reported to the maintenance team.

I muddled through the rest of the week before heading home to Austin. Losing my X1 was a huge loss for me, because a bunch of irreplaceable files on it were not backed up to the cloud, including tax return data files and a birthday video some friends had arranged from Cameo. Some code updates to my tools hadn’t yet been uploaded to GitHub, and I lost access to a variety of notes and other information that wasn’t copied elsewhere. One consolation was that I knew that I’d enabled BitLocker Drive Encryption on the main disk, so the company’s data was safe.

For decades I’ve been worried about losing files through human error. Unfortunately, I only backed up to external drives every month or two, instead relying on more frequent backups by copying to dated folders to a second SSD on the same machine. Because COVID WFH meant that my laptop rarely left my home office, my entire machine getting stolen just wasn’t a significant part of my threat model. Oops.

I held out some hope that Microsoft Campus Security had video of the thief, and indeed they did. They supplied it to the Redmond Police department. Apparently, the thief was a “known transient in the area” and for a few weeks I held out hope that might mean I would see my laptop again. As the months went by, I lost hope. Because the laptop was my personal machine in BYOD mode (I’ve long used exclusively my own hardware for work) Microsoft wasn’t going to buy me a new one. Depression and frustration about the situation doubtless contributed in part to my leaving the Edge team later that summer.

The next time I gave my missing ThinkPad any real thought was the following April, when I was doing my taxes and had to painstakingly reenter data and make my best guesses based on my recollections of the past year’s now-missing data. It was very frustrating, and I’m sure I paid a few hundred dollars more than I needed to, having lost carryover deductions.

The last time I really thought about my lost ThinkPad was two years ago, when someone stole my son’s iPad out of my car parked in front of my house. I immediately assumed it was gone forever, and rolled my eyes that Apple’s “Find My” was so dumb that it still showed the tablet outside my house. And not even directly in the driveway of my house, but like 300 feet away. And that location never updated in the following days. Annoyed, I finally grudgingly decided to meander down the block to the tiny grove of trees marked by the blue dot and … sure enough, the iPad was sitting there in the grass under a tree. The thieves were smart enough to realize that they weren’t going to be able to use or sell the iPad without its passcode. Amazing.

Years passed.

And then…

Improbably, two weeks ago I received the following email:

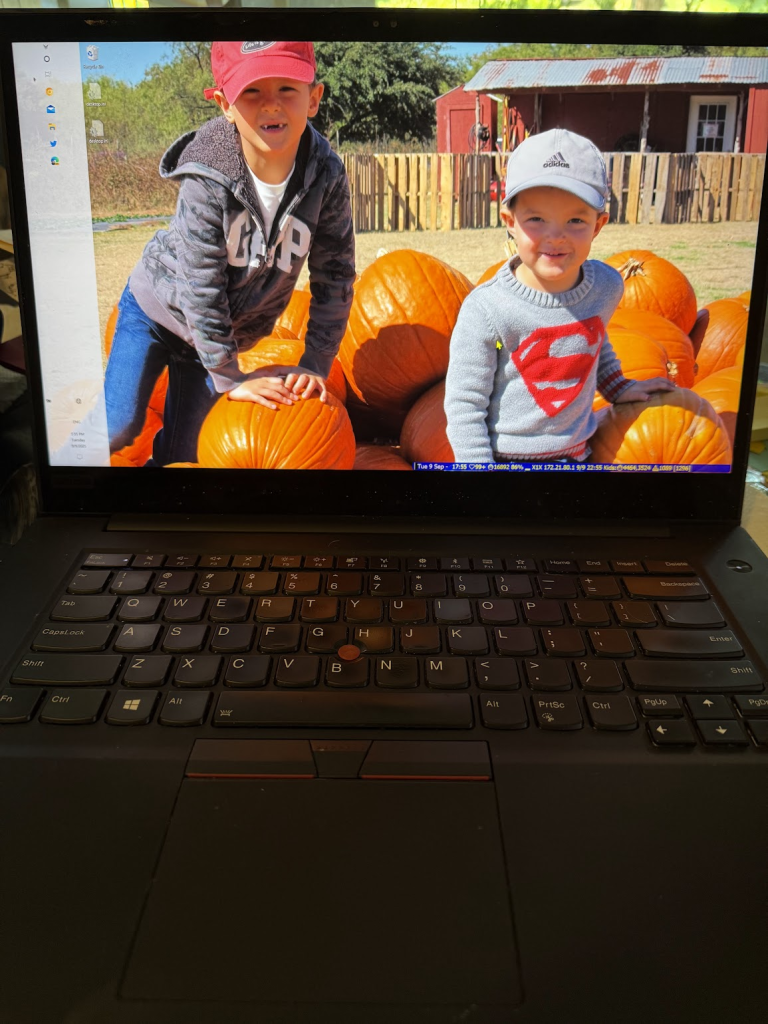

I clicked the link, and sure enough, there it was, my laptop with my name still on the screen:

The listing was posted 60 miles away from Redmond. I contacted the seller and in chats over the following week, more of the story came out. Alexandra bids on abandoned storage units, and a recent acquisition had a pile of laptops in it, including mine. She mentioned that the container also had another ThinkPad, which unlike mine, bore a “Microsoft Asset” sticker on it. (I grabbed that Asset number and told her that our Corporate Security team would be in touch.)

She shipped my laptop back to me (somewhat tenuously packed in just an envelope full of bubble-wrap) and it arrived this afternoon. The fun stickers that once adorned the face are gone without a trace, but it’s unquestionably my device.

I’m a little afraid to turn it on — I’m pretty sure when I do, it’s going to auto-connect to my WiFi, realize that it’s been marked stolen, and get automatically wiped. Still, even in the unfortunate event that such a wipe happens, I might still end up formatting and reinstalling Windows 11 on it — the X1 Extreme Gen1 was the last ThinkPad that I really liked (my more recent buys have been “meh“), and it probably has at least a bit of useful life left in it.

And there’s something kinda magical in having my long wandering machine finally, improbably, find its way home, one thousand two hundred sixteen days later….

Lessons

- If you see something, say something. I never would’ve gotten this laptop back if Howard didn’t reach out. It never would’ve been stolen to start with had the defective door been reported. (This advice goes for software bugs too!)

- Encrypt your disk. I would’ve been very very uncomfortable with my tax returns and other personal data floating around in the wide world.

- Regularly back up your data. Cloud backups are convenient, local offline backups provide additional assurance. Don’t forget your BitLocker keys!

-Eric

PostScript

Postscript: It looks like Microsoft Corp got rid of my device’s BitLocker disk encryption recovery key years ago, and I couldn’t find a copy of the recovery key file anywhere on my many external devices. (Consider backing yours up right now!)

But I randomly searched my other machines for text files containing the word “BitLocker” and found the X1’s key in an old SlickRun Jot file backed up from another laptop in 2022. I turned off WIFI in the X1 BIOS and successfully booted to my Windows desktop. It was a bit disorienting at first because the colors were all nuts — apparently, the last thing I was working on that fateful night in 2022 was a high-contrast bug. :)

Unfortunately, it looks like one component didn’t survive over the years — my beloved TrackPoint (the little red eraser-looking input device) only moves the cursor side-to-side, so I have to rely on the touch pad. But still, not bad at all.