Just over 5 years ago, I wrote a blog post titled “Misbehaving HTTPS Servers Impair TLS 1.1 and TLS 1.2.”

In that post, I noted that enabling versions 1.1 and 1.2 of the TLS protocol in IE would cause some sites to load more slowly, or fail to load at all. Sites that failed to load were sending TCP/IP RST packets when receiving a ClientHello message that indicated support for TLS 1.1 or 1.2; sites that loaded more slowly relied on the fact that the browser would retry with an earlier protocol version if the server had sent a TCP/IP FIN instead.

TLS version fallbacks were an ugly but practical hack– they allowed browsers to enable stronger protocol versions before some popular servers were compatible. But version fallback incurs real costs:

- security – a MITM attacker can trigger fallback to the weakest supported protocol

- performance – retrying handshakes takes time

- complexity – falling back only in the right circumstances, creating new connections as needed

- compatibility – not all clients are willing or able to fallback (e.g. Fiddler would never fallback)

Fortunately, server compatibility with TLS 1.1 and 1.2 has improved a great deal over the last five years, and browsers have begun to remove their fallbacks; first fallback to SSL 3 was disabled and now Firefox 37+ and Chrome 50+ have removed fallback entirely.

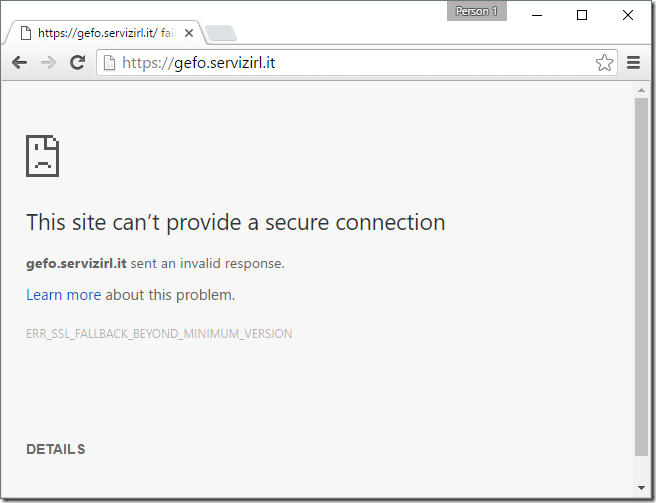

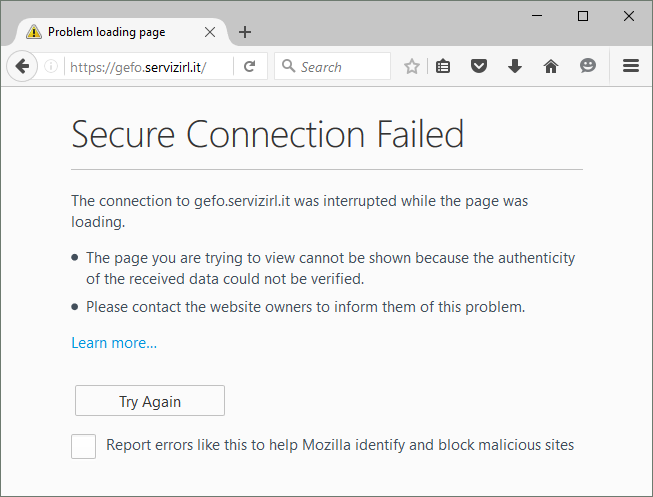

In the rare event that you encounter a site that needs fallback, you’ll see a message like this, in Chrome:

or in Firefox:

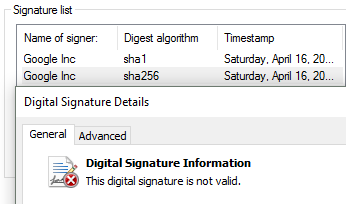

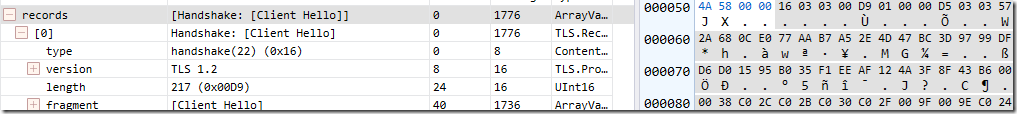

Currently, both Internet Explorer and Edge fallback; first a TLS 1.2 handshake is attempted:

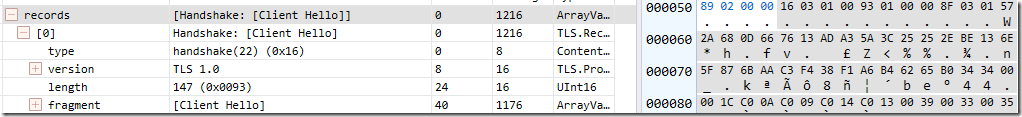

and after it fails (the server sends a TCP/IP FIN), a TLS 1.0 attempt is made:

This attempt succeeds and the site loads in IE.

UPDATE: Windows 11 disables TLS/1.1 and TLS/1.0 by default for IE. Even if you manually enable these old protocol versions, fallbacks are not allowed unless a registry/policy override is set.

EnableInsecureTlsFallback = 1 (DWORD) set inside

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings or

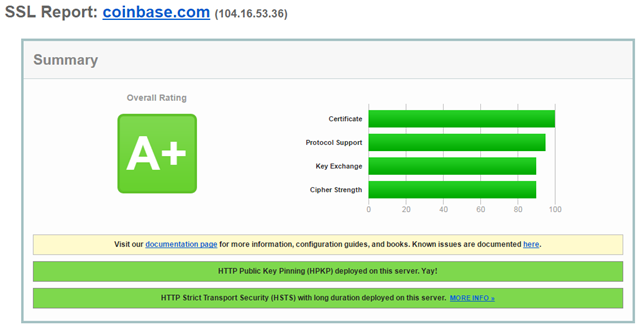

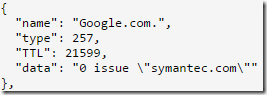

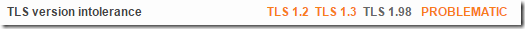

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Policies\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet SettingsIf you analyze the affected site using SSLLabs, you can see that it has a lot of problems, the key one for this case is in the middle:

This is repeated later in the analysis:

The analyzer finds that the server refuses not only TLS 1.2 but also the upcoming TLS 1.3.

Unfortunately, as an end-user, there’s not much you can safely do here, short of contacting the site owners and asking them to update their server software to support modern standards. Fortunately, this problem is rare– the Chrome team found that only 0.0017% of TLS connections triggered fallbacks, and this tiny number is probably artificially high (since a spurious connection problem will trigger fallback).

-Eric