Two experiences this week reminded me of a very important principle for improving the quality of software… if you see something, say something. And the best way to do that is to file a bug.

Something Weird? File a bug!

The first case was last Thursday, when a user filed a bug in Chrome’s tracker noting that Chrome’s window border icons often got “stuck” in a hover state after being moused over. It was a clear, simple bug report and it was easily reproduced. I’ve probably hit this a hundred times over the years and didn’t think much of it… “probably some weird thing in my graphics card or some utility I’m running.” It never occurred to me that everybody else might be seeing this, or that it was exhibited only by Chrome.

Fortunately, the bug report showed that this issue was something others were hitting too, so I took a look. The problem proved to be almost unique to Chrome (not occurring in other Windows applications), and has existed for at least seven years, reproducing on every version from Windows Vista to Windows 10.

A scan of the bug tracker suggests that Thursday’s report was the first time in those seven years that this bug was filed; less than a week later, the simple fix is checked in and on the way to Chrome 54. Obviously, this is only a minor cosmetic issue, but we want our browser looking good at all times!

Another cool aspect of this fix is that it will fix other applications too… the Opera and Vivaldi browsers are based on Chromium open-source roots and inherited this problem; they’ll probably pick up this fix shortly too.

th;df – Say Something Anyway

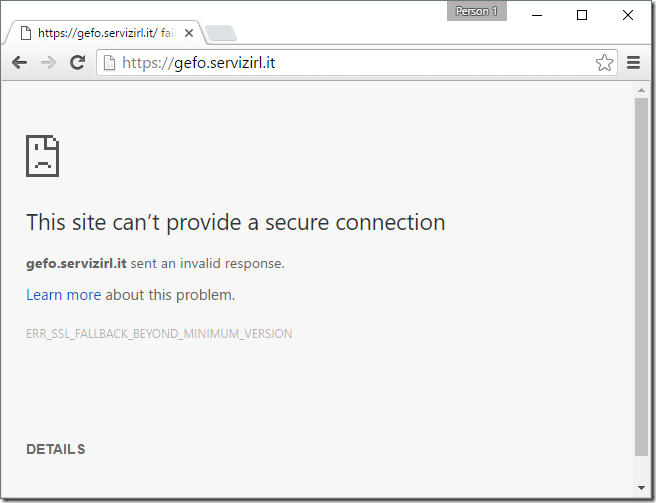

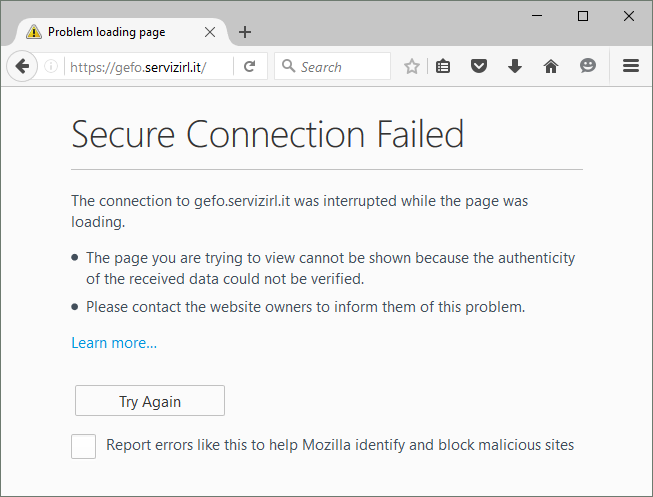

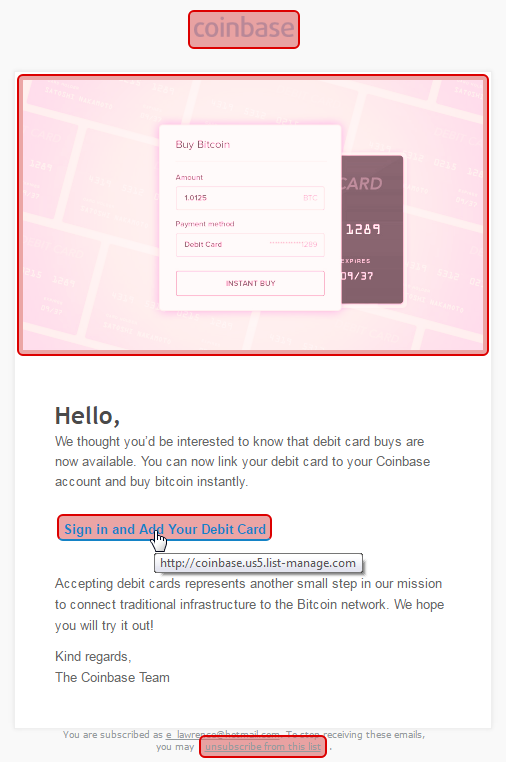

Even if you don’t file a bug, you should still say something. Recently, Ana Tudor noted on Twitter that her system was in a state after restart where neither Chrome nor Brave could render web content; both browsers showed the “crashed tab” experience, even after restarting and reinstalling the browsers. Running with the no-sandbox flag worked, and rebooting the system fully solved the problem. Her report sounded suspiciously similar to a problem I’d encountered back in April; fortunately, I’d filed a bug.

At the time, that bug was deemed unreproducible and I’d dismissed it as some wonkiness on my specific system, but Ana’s complaint brought this back to my attention. She’d also added another piece of data I didn’t have in my original report—the problem also occurred in Brave, but not Firefox or IE.

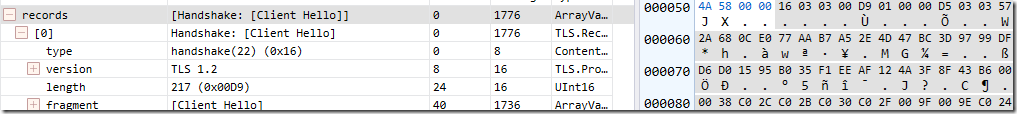

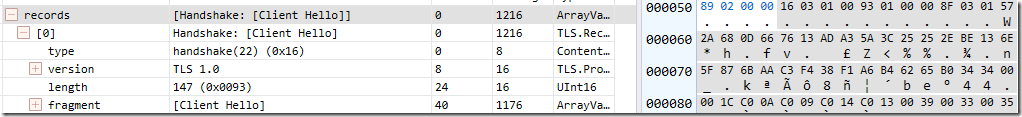

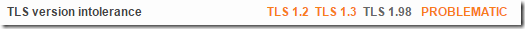

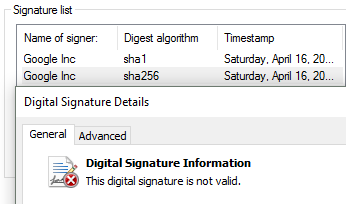

Even more fortunately, I hit this problem again after a system reboot yesterday, and because of Ana’s report, I was no longer convinced that this bug was some weird quirk on just my system. Playing with the repro, I found that neither Opera nor Vivaldi reproduced the problem; both of those browsers are architecturally similar to Brave, but importantly, both are 32-bit. So this was a great clue that the problem was specific to 64-bit. And I confirmed this, finding that the bug repro’d only in 64-bit Chrome Canary but not in 32-bit Canary. Now we’re cooking with gas!

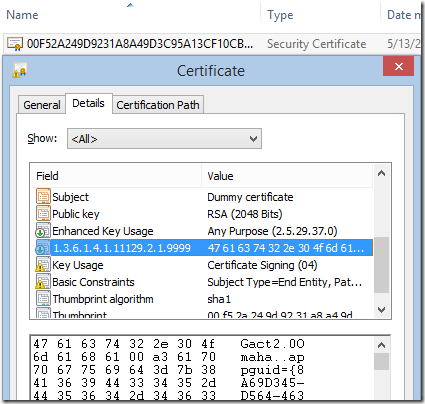

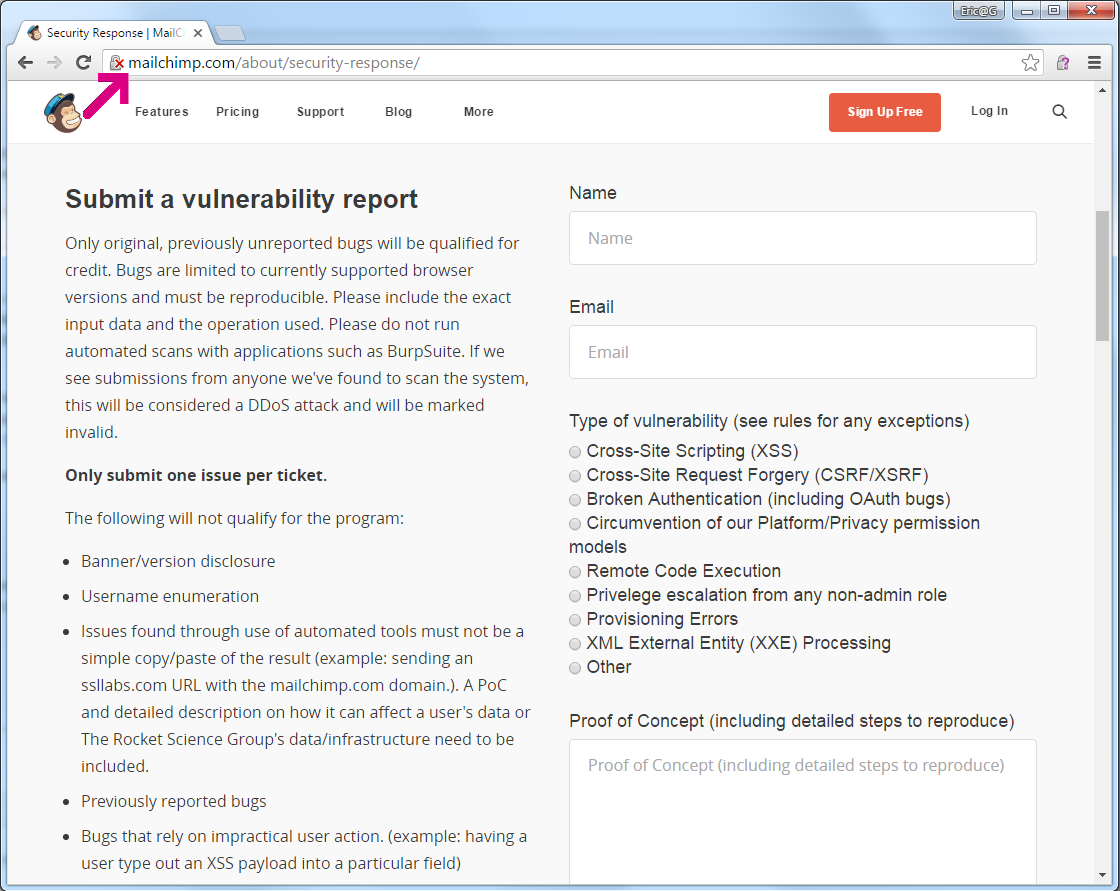

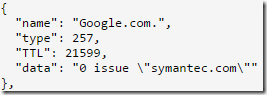

I built Chromium and ran it through WinDBG, seeing that when the sandboxed content renderer process was starting up, it was hitting three debug breakpoints before dying. The breakpoints were in sandbox::InterceptionAgent::OnDllLoad, a function Chrome uses to thunk certain Windows APIs to inject security filters. At this point, and with a reliable repro in hand, my smarter colleague took over and quickly found that the code to allocate memory for the thunk was failing, due to some logic bugs. Thunks must be located at a particular place in memory – within 2gb of the thunked function – and the code to place our thunks was failing when ASLR randomly loaded the kernel32, gdi32, and user32 DLLs at the very top of the address space, leaving no room for our thunks. When the allocation failed, Chrome refused to allow the DLL to be loaded into the sandbox, and the renderer necessarily died. After the user rebooted the system again, ASLR again moved the DLLs to some other location and (usually) this location gives us room to place our thunks. With 20/20 hindsight, the root cause of this bug (and the upcoming fix) are obvious.

But we only knew to look for the problem because Ana took the time to say something.

Final Thoughts

- Browser telemetry is great—we catch crashes and all sorts of problems with it. But debugging via telemetry can be really challenging— more akin to solving a mystery than following a checklist. For instance, in the case of the sandbox bug, the fact that the problem reproduced in Brave was a huge clue, and not something we’d ever know from telemetry.

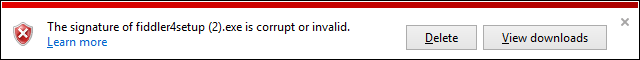

- Well-run projects love bug reports. Back when I was building Fiddler, a lot of users I talked to said things like: “Well, it’s free and pretty good so I didn’t want to bother you with a complaint about some bug.” This is exactly backwards. For most of Fiddler’s lifetime, bug reports from the community were the only compensation I received from making the tool available to everyone for free. Getting bug reports meant I could improve the product without having to pay for test machines and devices, hire a test organization, etc, etc. When I eventually sold Fiddler to Telerik, a large part of the value they were buying was the knowledge that the tool had been battle-tested by millions of users over 9 years and that I’d fixed thousands of bugs from that community.

- Filing bugs is generally easy, and it’s especially easy for Chrome.

- First, simply search for an existing bug on crbug.com

- If you find it’s a known issue, star it so you get updates

- If it’s not a known issue, click the New Issue button at the top-left

- Tell us as much as you can about the problem. Try to put yourself in the reader’s shoes—we don’t know much about your system or scenario, so the more details you can provide, the better.

- Screenshots and URLs that reproduce problems are invaluable.

- Find a bug in another browser? Report it!

Thanks for your help in improving our digital world!

-Eric