I do not come from an especially political family. One parent has not voted in decades, and the other votes regularly, but is not an enthusiast and values harmony over potentially-divisive political discussions. Politically, I am left of center– the middle child in both age and political leanings: one brother to the left of me, and one brother to the right.

As a kid, my parents thought Republicans were the good guys. Bill Clinton’s depravity didn’t help matters at all. In high school, I had one Political Science teacher who challenged my default “I’m a Republican, I guess” posture, but I still skipped voting for Al Gore when I turned 18 as I didn’t care enough to bother in deep-blue Maryland. As a college freshman, I studied early American history and read many of the letters and musings of America’s founders, gaining a much broader understanding of the amazing story behind the founding of this nation, the risks the founders faced, and the compromises that linger to this day. Thus was birthed my interest in politics.

Our Revolutionary Founders (Jefferson in particular), concluded that the only way for a government to be responsive to its citizenry was to have it be periodically overthrown. Rather than suffer the losses and uncertainty of violent overthrow, the notion of regular, peaceful overthrow of the government was seen as the best approach. We call these peaceful revolutions elections.

“I am not an advocate for frequent changes in laws and Constitutions. But laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths discovered and manners and opinions change, with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also to keep pace with the times. We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.”

Thomas Jefferson

I watched The West Wing and thought it was brilliant. John Kerry visited Microsoft, gave a nice speech, and I read his book and voted for him in 2004. In 2008, I eagerly voted for Obama, although I greatly respected John McCain until his disastrous choice of running mate. I voted for Obama again in 2012 although I believe, gaffes aside, the country would be just fine under Romney. I watched The Newsroom, and I still believe that its opening scene is the best and most important five minutes of television ever made. In 2016, I voted for Hillary, despairing that Trump was even a contender for the nation’s highest office. In 2020, I supported Buttigieg and Warren in the primaries, holding my nose to vote for Biden in the general (I think Biden is an admirable patriot and his reward for a lifetime of public service should be a pleasant retirement, not working into his 80s.)

I was furious that Biden announced that he’d run again in 2024, and that both parties had failed to prepare the next generation of leaders to take over. For durable improvements, Systems must be treated as more important than Individuals.

On the first day of early voting, I voted for Harris, and thought she’d be a fine President for all Americans.

On The Issues

Guns are now the leading cause of death for American children. This is an insane travesty, and it’s a stain on our nation that so little has been done about it. More locally, Texas has significantly loosened its gun laws over the last twelve years, with predictably tragic results.

My thoughts on civilian ownership of firearms could fill a book. It’s not a simple issue, but the status quo is barbaric and unacceptable.

Climate Change: Austin just notched its hottest October in history. Atop Kilimanjaro in 2023, I saw the sad state of the depleted glaciers, and I worry that there may be nothing left when I summit again on New Years’ Eve just before the calendar ticks over to 2026. I can’t help but believe that technology is going to bail us out (yet again) and we’ll avoid the worst projections. But we are playing with fire, and we risk activating tipping points we don’t even know about. As with most things, the poor and powerless are going to pay most of the price.

Taxes: It’s common for those on the left to scream “Tax the rich! Make them pay their fair share!” This clip from West Wing is a great and important one– we should tax the rich more (Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, to their credit, both agree). But we must acknowledge that most of the wealthy pay much more in taxes than the average American, and it’s crucial to recognize that even if we taxed the rich at a rate of 100%, we would not be able to balance the budget for long. I’m particularly fond of someone’s flippant proposal that we should require the super-wealthy pay higher taxes, and in return get naming rights for infrastructure– $10M for a Post Office, $5M for a Bridge, etc.

Still, I’ve come around to the notion that the existence of billionaires is a policy failure, and there are absolutely insane loopholes in the tax code (e.g. this IRA hack, “step-up basis” on inheritances, etc) that should go away.

I’m infuriated that so many on the political right should be voting for higher taxes on those who can afford them, but do not do so because “the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat, but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” The rich see you as suckers.

Hard choices must be made, and our system is such that politicians are punished for making them.

The Spending side represents the other side of hard choices; as a society, we must choose how to allocate our limited resources. There are many worthy causes, but we cannot afford them all. Prioritization matters.

For example, the United States is set to spend a trillion dollars ($1,000,000,000,000!) on modernization of our nuclear arsenal, and I don’t think we talk nearly enough about whether that’s the best way to protect Americans against the true threats of the 21st century.

Unintended consequences abound: The US has the most expensive educational system and most expensive healthcare system in the world, and that’s not only because of greed– it’s partly because of some well-meaning policy choices we’ve made have had some awful and unforeseen consequences. We should not be afraid to change things, but we must also refine those changes as we observe their outcomes.

However, it’s almost as great a mistake to think of the United States’ budget as that of a family– money simply works very differently when you control the supply, interest rates, and other key aspects of the worldwide financial system.

Despite the complexity, common sense suggests some simple heuristics. When considering an expenditure, we should ask “Is it an investment, neutral, or worsening some larger problem? Is the money going to a fellow citizen, an ally, or an enemy?” I’d love to see the $800B-$1T a year we spend on the military-industrial complex pivoted to the future-industrial complex.

Abortion: I have a deep ambivalence about abortion– extremists exist on both sides of the divisive issue, and most folks refuse to think deeply about the implications of their own position, let alone listen to those on the other side. Any litmus test is a prime target for abuse.

After decades of thinking about this, I’ve settled into a simpler position: “Abortion is healthcare,” and believe that’s where the political realm should leave it.

Trump: Truer words were never spoken: “Trump is a poor man’s idea of a rich man, a weak man’s idea of a strong man, and a stupid man’s idea of a smart man.” This incurious, impetuous liar is remarkable only for his utter shamelessness.

Trump is both a symptom of great rot in American society, and an accelerator of that decay. Trump claims to “love the poorly educated“– not because he aims to improve their life and help their family attain the American Dream, but because he knows a sucker when he sees one.

Some more moderate Trump voters assume: “Meh, the worst of his plans are just talk, they’ll never actually happen.” They do not understand that Trump 2.0 is a version with far fewer checks, and they failed to heed the (belated) dire warnings of those who worked for him last time. In the same way that Trump uses the poorly educated as “useful idiots,” evil people much smarter than Trump (foreign and domestic) will use our President as their useful idiot.

Politicians: I’ve learned that there’s a class of Trump voters who know he’s an awful person but voted for him because he’s entertaining. They assume that politicians are ineffective and almost interchangeable liars, so the person in the Oval Office doesn’t really matter. That’s a position not entirely without support, but one that falls apart when our institutions and checks-and-balances fail or are subverted. Trump’s backers have been working to undermine our institutions for decades.

Some people have been convinced (often by folks like cosplay cowboy Harvard-educated Ted Cruz) that politicians are out-of-touch “elitists” who “think they’re better than us.” I’m reminded of this cartoon in the New Yorker:

In the same way that I want my manager at work to be smarter and harder working than I am, when I vote, I want to hire someone for the job who’s better than me in every way possible.

The Democrats: I am still furious that the Democratic Party supported Trump in the 2015 primaries, literally betting the future of our country on the idea that a racist rodeo clown couldn’t possibly lie his way into the most important job in the world. We all lost in that bet.

Bob Menendez should not have been granted the opportunity to resign; he should have been expelled.

Partisanship: Too many of us interested in politics follow it like sports– cheering for the home team (no matter what), and booing the opposition (no matter what), and demanding “loyalty” to one’s own party regardless of malfeasance or foolishness. Instead of finding common ground with our neighbors, we’re split into factions as many politicians prefer. The truth is that all states are shades of purple. As hard as the Republicans want to convince Texans that it’s a “Deep Red” state, more Texans than New Yorkers voted for Biden.

We should not be afraid to hold our own “side” (and selves) accountable, no matter our opinion of others.

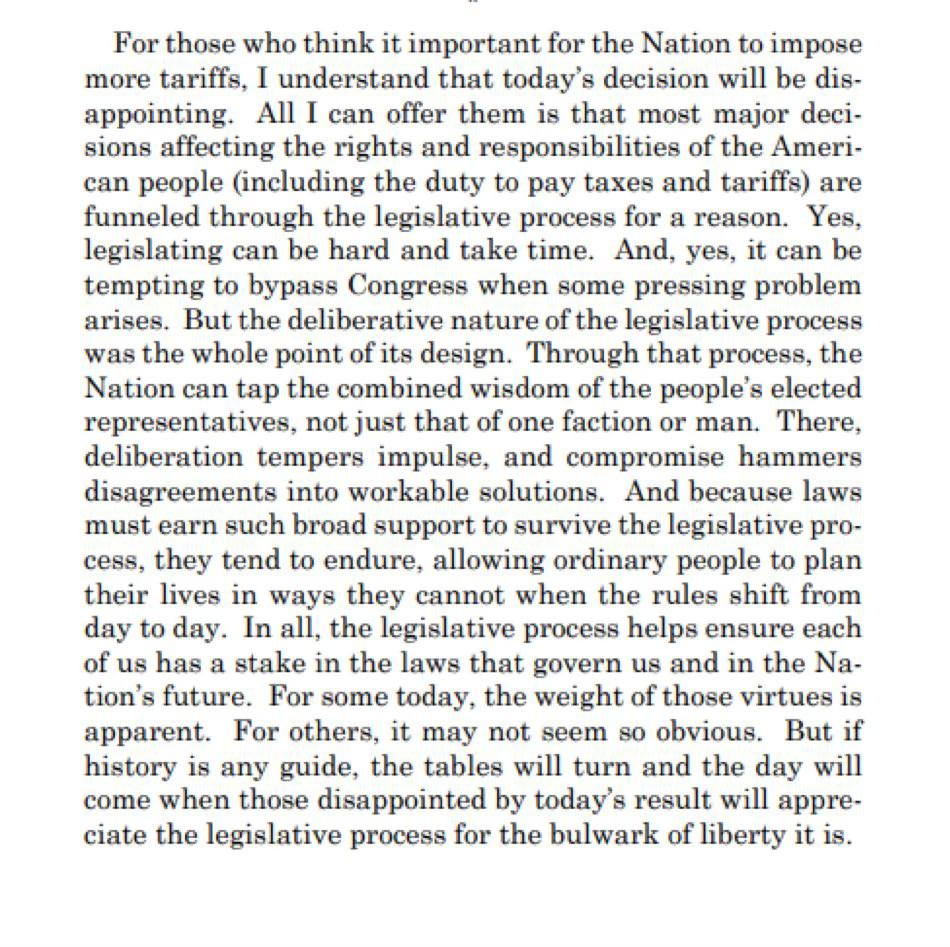

The Supreme Court: For many years, the Supreme Court was the branch of government that I respected most. Justices mostly kept their mouths shut when it came to politics, and an appointment is not a stop on the way to a highly-paid lobbyist job. Justices never have to pander to the base to win their next election. Most importantly, unlike Congress, the Justices have to show their work in written opinions that will be scrutinized for decades. In many of the painful decisions overturning good (and evil) things, the Court has simply held that a given good thing requires that Congress write a law.

Unfortunately, Congress has been mostly dysfunctional for many years now, failing to serve the American people in their constitutional duty.

More recently, however, the court has been tarnished by acceptance of improper gifts, political speech, and other scandals. More practically, a system where we incentivize or demand that the elderly work until they die (based on the vagaries of presidential elections) is a grotesque one. Thus far, the best proposal I’ve seen is to term-limit Justices to 18 years— a period long enough to help protect impartiality, but not so long as to make an appointment a life-sentence and the highest stakes action a Senate will ever conduct.

The American Electorate: Unfortunately, fear is a primary driver of voting behavior, and we humans have a set of base fears (particularly “fear of the other”) that politicians have learned to play like an instrument. This year, Ted Cruz spent millions of dollars on ads about immigrants and children’s genitalia, and he, the least popular Senator in a decade, sailed to reelection. Trump spent $65M on ads about genitals. As the world’s real challenges grow greater (aging populace, climate calamities, plagues, AI job displacement), greater fear is sure to follow.

The vote of an ignorant racist counts just as much as the thoughtful patriot, and “all the terrible people vote.” I’m as angry about politically apathetic non-voters as I am about the suckers who voted for the blowhards, the bigoted, and the hateful. Anyone who can look at Harris and Trump and think “Meh, no opinion here” needs to stop sniffing glue. And yes, the Republican party has been working for decades to make it harder for Americans to vote, but it’s just a weak excuse for many of the large block that do not vote:

While it’s easy to lament how disastrous the consequences of the 2024 elections will be, it’s important that elections have consequences. Without consequences, elections don’t matter. And if elections don’t matter, you’re no longer living in a democracy. As Dan Stevens taught in 7th grade civics, at a societal level, Democracy means you get the government you deserve.

Looking Forward

America is about to enter the “Finding out” phase of “Fuck around and find out.” Feedback loops are important, and the tighter they are, the more effective they are. Unfortunately, political feedback loops can take years or even decades between cause and effect.

After the 2024 election, the super-rich (Musk, Bezos, and the like) will be just fine. The merely-rich who supported Trump are going to find themselves like the UK Rich post-Brexit — when your entire economy gets kicked in the nuts, your personal tax rate is not the important factor in your wealth. An ebbing tide lowers all boats. As is common, the middle-class and poor are going to get hurt, and hurt bad, whether they supported Trump or not.

For now, though, I can’t let myself get too lost in despair for our world. Ultimately, we each only have so much control over our reality, and the main thing under our control is how we react to it. Catastrophizing (and anxiety more generally) is only useful if it inspires productive action.

This week, I’m taking a breath and looking around with both trepidation and curiosity. Maybe America, as a country, isn’t better than this. But even if that’s the case, we can be.

Hope is a thing that fights in the dark.

-Eric

PS: I recently moved from Twitter to BlueSky.