The Web Platform offers a handy API called pushState that allows a website’s JavaScript to change the URL displayed in the address bar to another URL within the same origin without sending a network request and loading a new page.

The pushState API is handy because it means that a Web Application can change the displayed URL to reflect the “current state” of the view of the application without having to load a new page. This might be described as a virtual navigation, in contrast to a real navigation, where the browser unloads the current page and loads a new one with a different URL.

For example, if I click the Settings link in my mail application, the URL may change from https://example.com/Inbox to https://example.com/Settings while JavaScript in the page swaps in the appropriate UI to adjust the app’s settings.

function onSettingsClick() {

ShowSettingsWidgets();

history.pushState({}, '', '/Settings');

}Then when I click the “Apply” button on the Settings UI, the Settings widgets disappear and the URL changes back to https://example.com/Inbox.

function onApplySettingsClick() {

CloseSettingsWidgets();

history.pushState({}, '', '/Inbox');

}Why would web developers bother changing the URL at all? There are three major reasons:

- Power users may look at the address bar to understand where they are within a webapp.

- If the user hits F5 to refresh the page, the currently-displayed URL is used when loading content, allowing the user to return to the same view within the app.

- If the user shares or bookmarks the URL, it allows the user to return to the same view within the app.

pushState is a simple and powerful feature. Most end-users don’t even know that it exists, but it quietly improves their experience on the web.

Unfortunately, this quiet magic has a downside: Most IT Administrators don’t know that it exists either, which can lead to confusion. Over the last few years, I’ve received a number of inquiries of the form:

“Eric — I’ve blocked https://example.com/Settings and confirmed that if I enter that URL directly in my browser, I get the block page. But if click the Settings Link in the Inbox page, it’s not blocked. But then I hit F5 and it’s blocked. What’s up with that??”

The answer, as you might guess, is that the URL blocking checks are occurring on real navigations, but not virtual navigations.

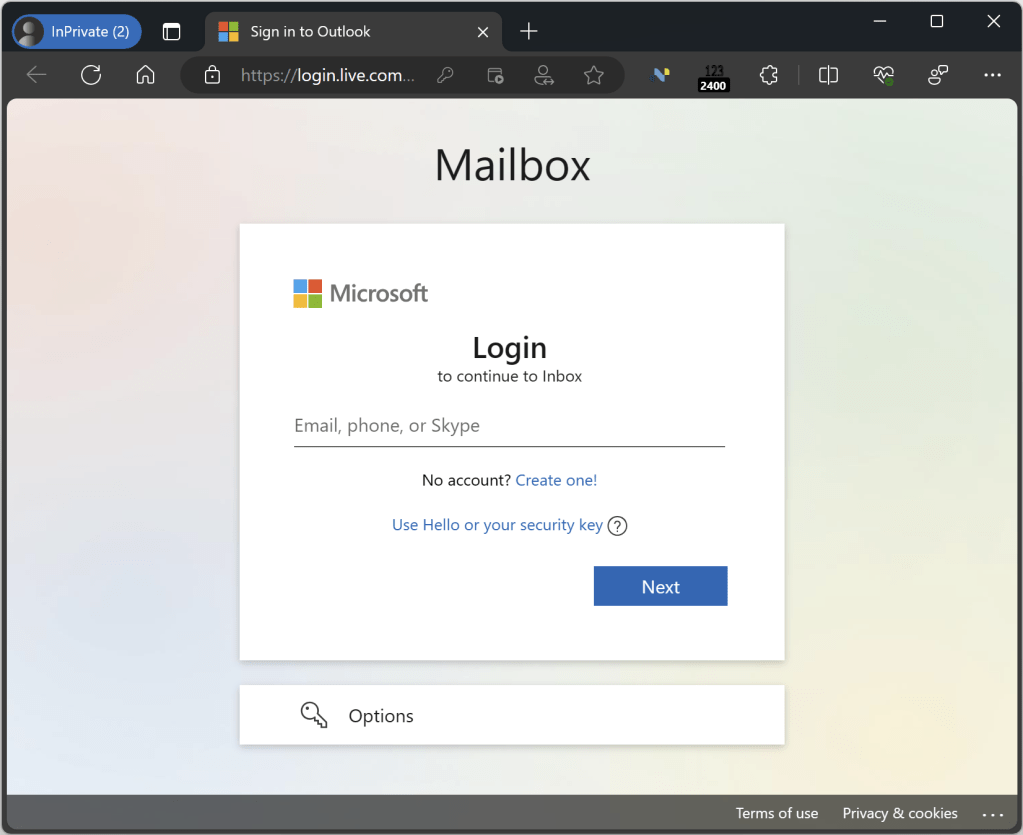

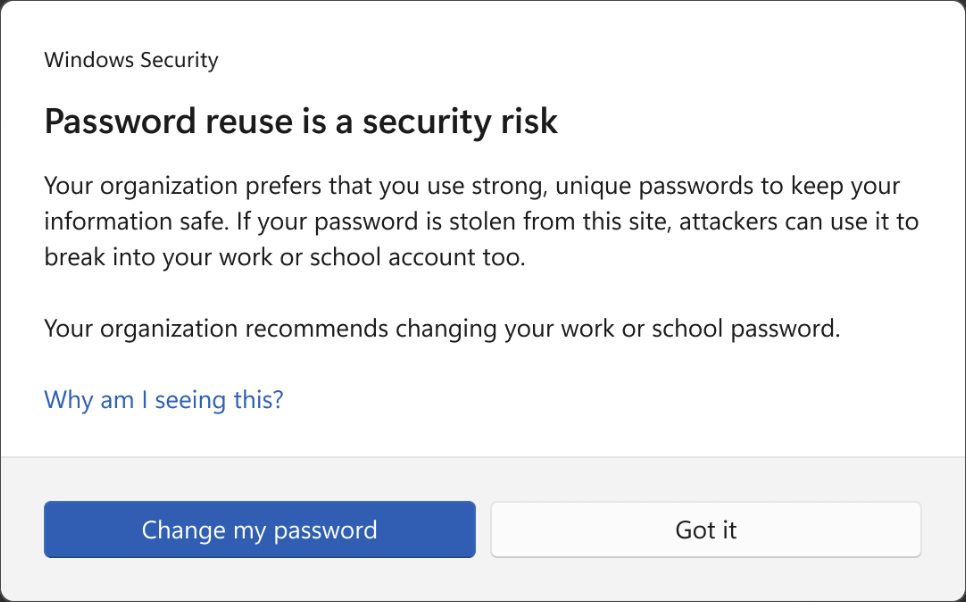

Consider, for example, the URLBlocklist policy for Chromium that allows blocking navigation to a specific URL. By default, attempting to directly navigate to that URL with the policy set results in a block page:

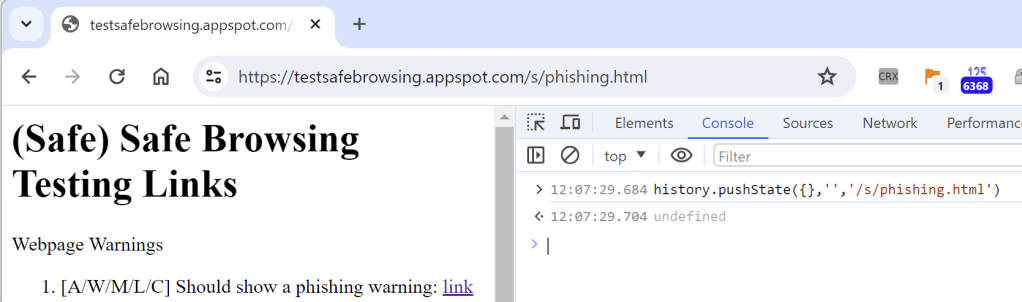

But if you instead navigate to the root example.com/ url, then use pushState to change the URL to the same URL, no block occurs:

…Until you hit F5 to refresh the page, at which point the block is applied:

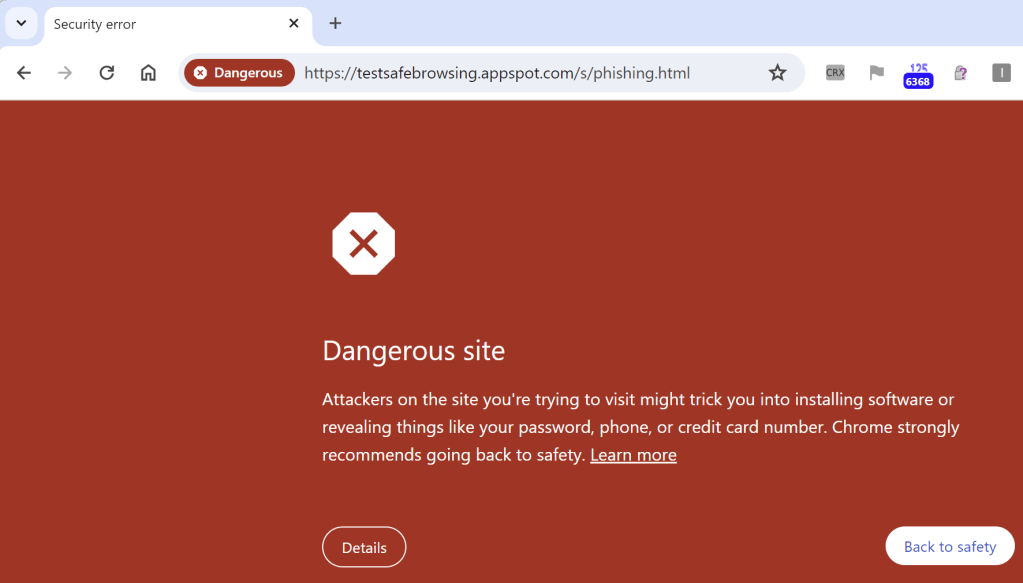

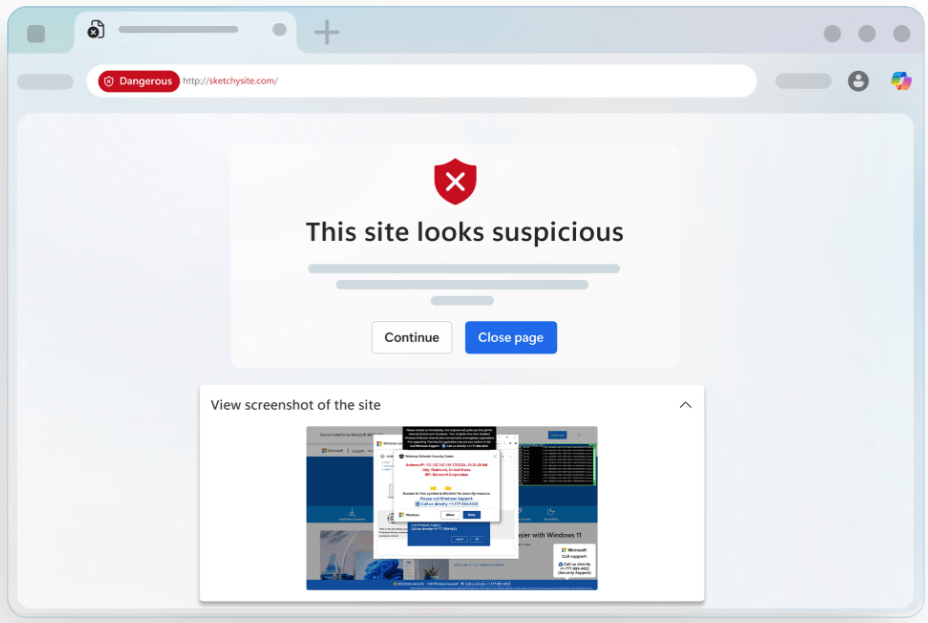

Similarly, you can see the same thing with test pages for SmartScreen or SafeBrowsing. If you click on the first test link in the SafeBrowsing test page, you’ll get Chrome’s block page:

…but if you instead perform a virtual navigation to the same URL, no block occurs until/unless you try to refresh the page:

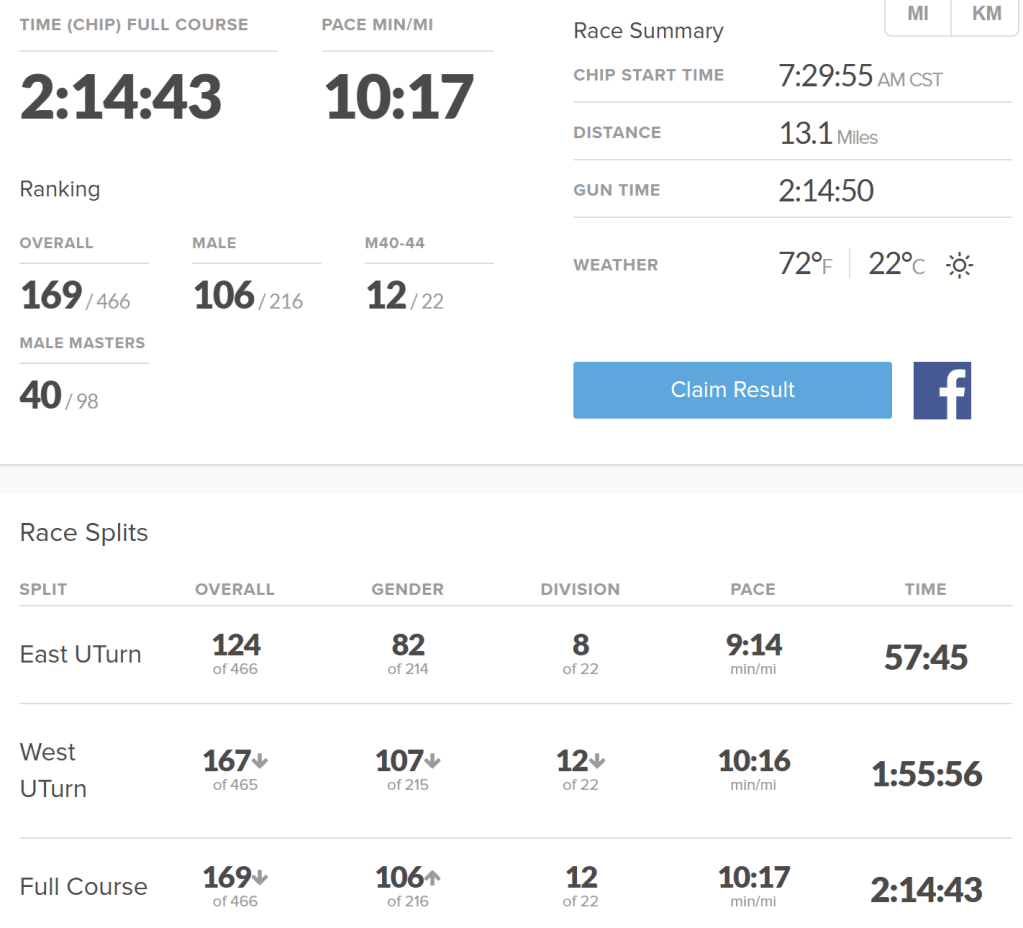

Similarly, if you create a Custom URL Indicator in Defender’s Network Protection for a specific URL path, you’ll find that a direct navigation to that URL is blocked in Edge, but not if you change the URL using pushState.

Blocks that are implemented by browser extensions typically are bypassed via pushState because the chrome.webNavigation events do not fire when pushState is called. An extension must monitor the tabs.onUpdated event if it wishes to capture a URL change caused by pushState.

Debugging

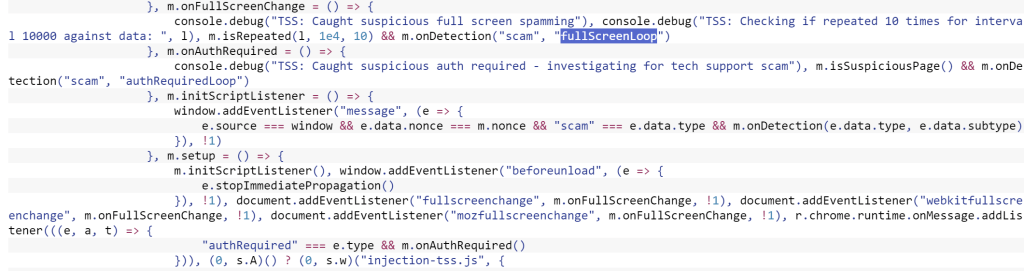

To see whether a virtual navigation is occurring due to the use of pushState, you can open the F12 Developer Tools and enter the following command into the console:

window.history.pushState = (a,b,c)=>{alert('Tried to pushState with :\n' + a + '\n'+b+'\nURL:'+c); debugger;}This will (until reload) replace the current page’s pushState implementation with a mock function that shows an alert and breaks into the debugger.

When clicking on the “Signup” link on the page, we see that instead of a true navigation, we break into a call to the pushState API:

You can experiment with pushState() on a simple test page.

Security Implications?

This pushState behavior seems like a giant security bug, right?

Well, no. In the web platform, the security boundary is the origin (scheme://host:port). As outlined in the 2008 paper Beware Finer-Grained Origins, trying to build features that operate at a level more granular than an origin is doomed. For example, trying to apply a special security policy to https://example.com/subpath, which includes a granular path, cannot be secured.

Why not?

Because /subpath is in the same-origin as example.com, and thus any page on example.com can interact (e.g. add script) with content anywhere else on the same origin.

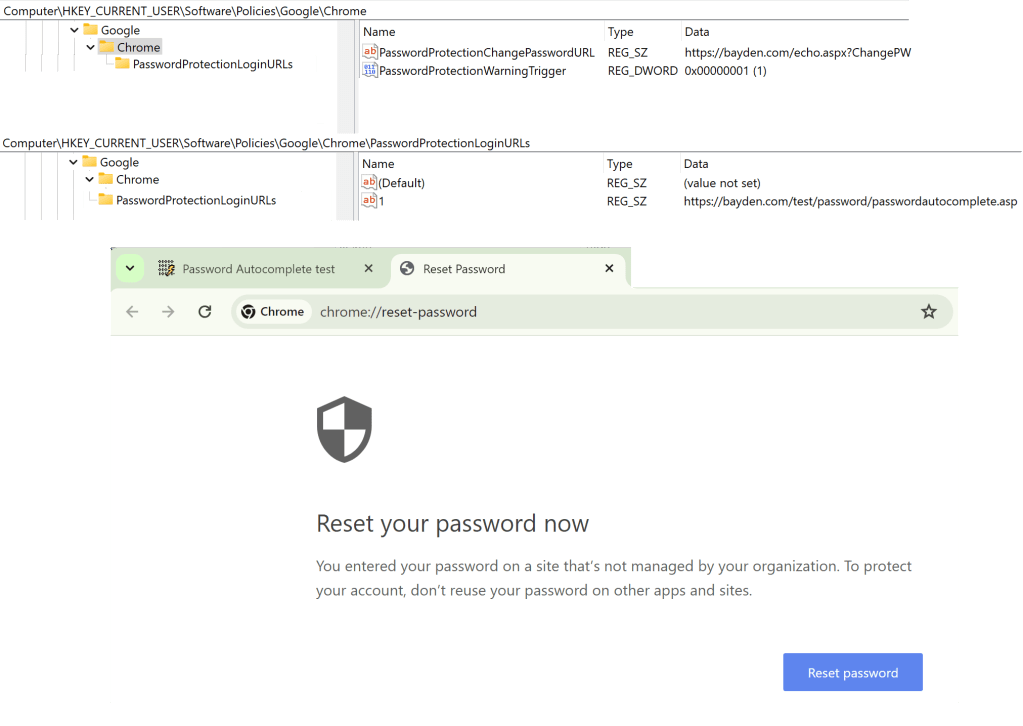

Security features like SafeBrowsing and SmartScreen will typically perform “rollups”, such that if, for example, evil.example.com/phish.html is a known phishing page, the URL Reputation service will typically block all of evil.example.com if it’s believed that the attacker controls the whole origin.

For an IT Administrator, pushState represents a challenge because it’s not obvious (without debugging) whether a given site uses virtual navigations or not. If you absolutely must ensure that a user does not interact with a specific page, you need to block the entire origin. For features like Defender’s Network Protection, you already have to block the entire origin to ensure blocking in Chrome/Firefox, because network-stack level security filters cannot observe full HTTPS URLs, only hostnames (and only requests that hit the network).

Update: Navigation API

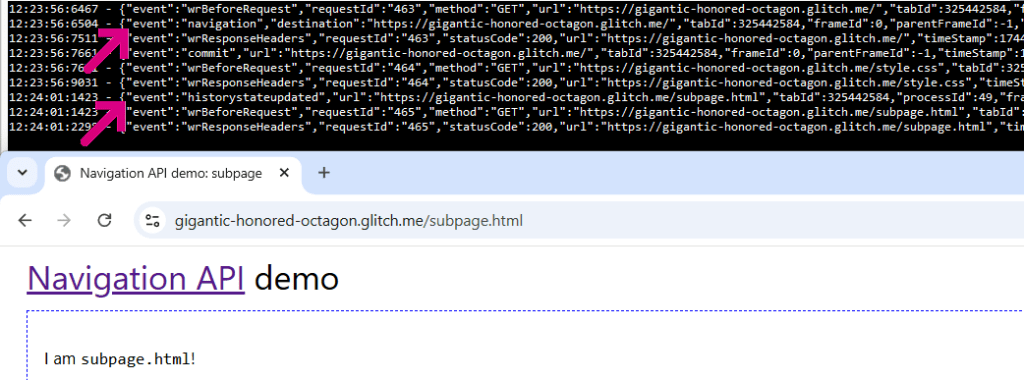

The new Navigation API appears to behave much like pushState.

Using an extension I wrote to monitor the browser on Navigation API demo site, you can see that clicking on a link results only in the URL update and fetch of the target content, but the browser’s webNavigation.onBeforeNavigate event handler isn’t called.

-Eric