While I’ve been running less, I haven’t completely fallen out of the habit, and I still find spending an hour on the treadmill to be the simplest way to feel better for the rest of the day. Real-world racing remains appealing, for the excitement, the community, and for the forcing function to get on the treadmill even on days when I’m not “feeling it.”

Alas, I’m not very proud of any of my fall race times, but I am glad that I’ve managed to keep up running after the motivation of Kilimanjaro has entered the rear-view mirror, and I’m happy that I recently managed to sneak up on running my longest-by-far distance.

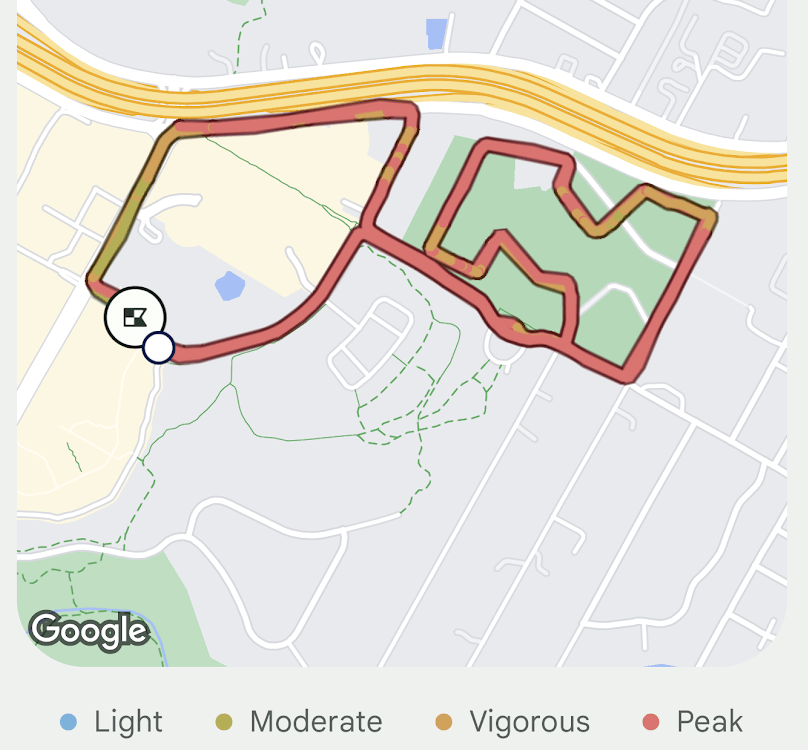

Daisy Dash 10K – 10/22

I had lucky bib #123 for this run. The course wasn’t much to look at, but was pleasant enough, looping around a stadium and a few shopping centers in “Sunset Valley” on the south side of Austin. I was worried going out that my lower back had been sore for a few days, and my belly felt slightly grumbly, but once I started running, neither bothered me at all for the next few hours. Thanks, body!

It was a 68 and breezy; a bit humid, but not nearly as bad as the Galveston Half I ran 9 months ago. I brought along an iPhone and Bluetooth earbuds and for my second race without music, after having stupid technical problems. In Galveston, my earbud died, and this time, I’d failed to download any music. Doh!

I burned 910 calories, and while my heart rate wasn’t awesome, it recovered quickly whenever my pace dropped.

I started out reasonably strong, finishing the first 5K in 26:39. I was wearing my Fitbit watch, but immediately abandoned any attempt to use it to monitor my pace during the run. I’m pleasantly surprised to find that I naturally settled into the exact 7mph pace that is my most common treadmill default.

Sadly, after the first 5K, I was panting and started taking 30 to 90 second walking breaks every three quarters of a mile or so, dropping my pace significantly in the back half of the race.

I tried to psych myself up with thoughts of Kilimanjaro and how short this race was (only 10K! I keep thinking), but I never got into that heavenly rhythm where the minutes just slide by for a while.

Still, I vowed to finish in under an hour, and in the last mile I was excited that I might beat 58 minutes, putting me about 5 minutes behind my second Cap10K in the spring, and still 10 minutes faster than my first real-world 10K.

Ultimately, I finished in 57:40:

While my arches felt a bit sore after the race (pavement is clearly much harder on me than my treadmill), I felt like running an extra four miles wouldn’t’ve been a nightmare… good news for the “Run for the Water” 10 miler coming up in two short weeks. But first, a charity 5K.

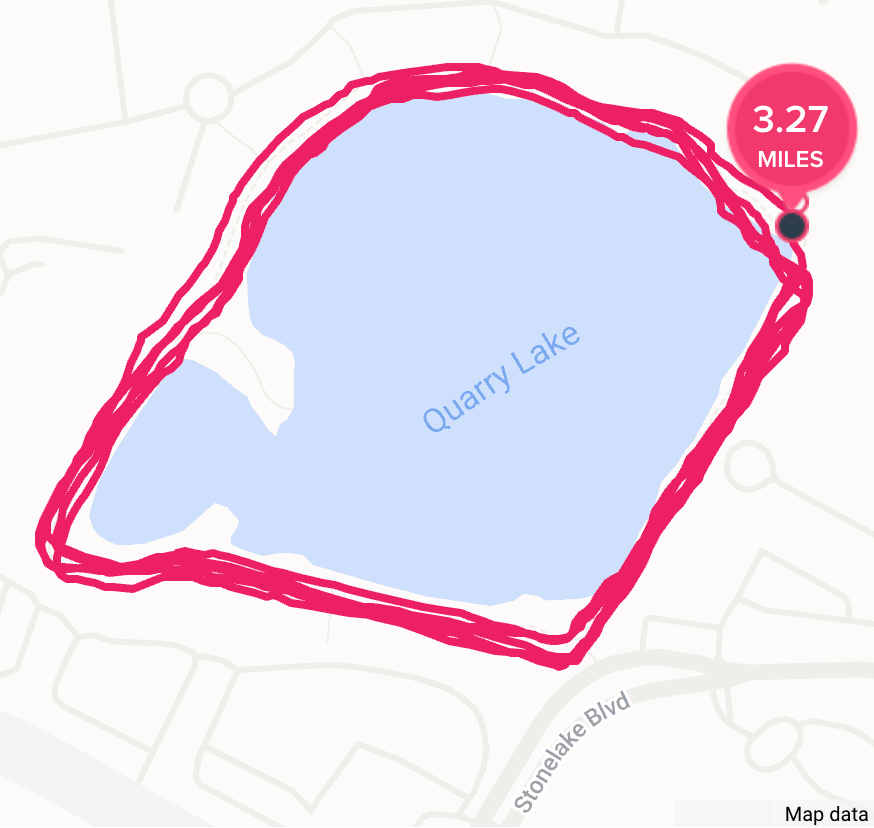

Microsoft Giving Campaign 5K – 10/27

The Microsoft Giving Campaign’s charity 5K consisted of five laps around a small lake near Microsoft’s north Austin office. It was fun to meet other Microsoft employees (many of whom started during the pandemic) and go for a fun run around the private Quarry Lake trail.

Alas, I had a hard time with my pacing and less fun than I’d expecting dodging the mud puddles.

In total, it took me 32:41 to run the slightly-extended (3.27) course.

Last year’s 5K was on a different course and I’d gone out too fast, ultimately needing to walk in the third mile, such that when I finished it, I turned around and ran the full course again, this time at a steady pace. While I don’t seem to have recorded my times anywhere, I think both runs were around 27 minutes.

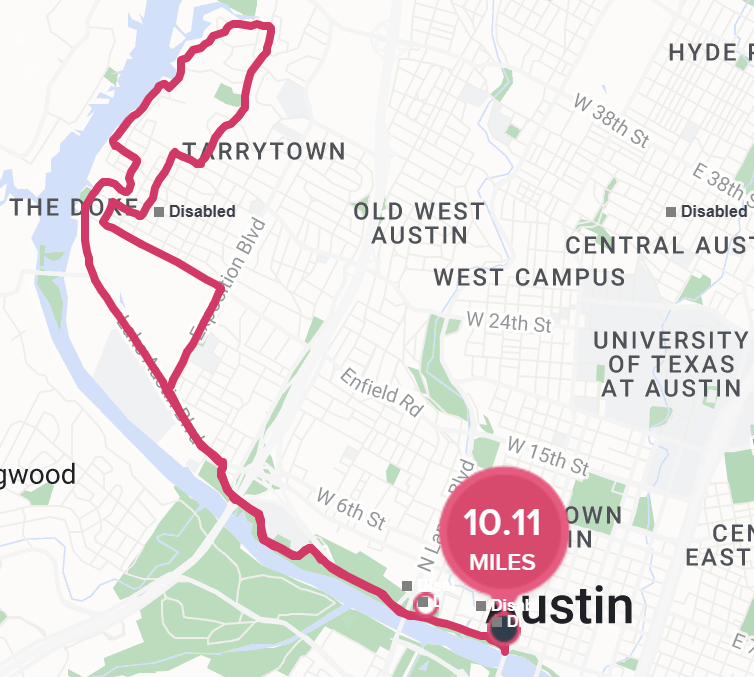

Run for the Water – 10 Miler 11/5

The weather for the race was nearly perfect. I was nervous, having remembered last year’s race, but excited to revisit this race with another year’s worth of running under my belt.

I managed the steep hill at mile 5.5 well, but fell off pace at miles 8 and 9.

Sprinting at the end, my sunglasses went flying off my shirt; embarrassingly, I had to loop back into the finishers’ chute after crossing the finish line to collect them.

I finished in 1:38:05, a pace of 9:48, a somewhat-disappointing 9:08 slower than last year‘s race. Ah well.

Turkey Trot 5-Miler 11/23

I arrived for the Thanksgiving day race very early and ended up spending almost an hour outside before the race began, getting a bit colder than I’d’ve liked. I warmed up quickly when the run began.

I finished in 45:45, a pace of 9:09, a bit (1:39) slower than last year.

Shortly before the race started, I made the poor decision to eat a free granola bar and it didn’t sit well during the run. After sprinting through the finishers chute, I spent a panicked half-minute trying to find a convenient place to throw up amongst the thousands of bystanders until my heart calmed down and the urge subsided.

Virtual Decker Challenge Half 12/9

Having surveyed the boring Decker Challenge course last year while driving by during my missed half, I decided to sign up for the virtual option this year. The 2022 shirt (made by Craft) has become one of my favorites, and I wore it constantly on Kilimanjaro, including on summit day. I registered for the Virtual event to collect this years’ shirt, but alas, it turned out to be a disappointing no-name black long-sleeve tech shirt. There were basically no other perks to the virtual race — no medal, and nowhere even to report your virtual results. Bummer.

For the race itself, I chose to repeat the Jackson Hole half that I ran last year, beating last year’s time by almost 4 minutes, with a time of 2:00:20. This wasn’t a great time, but I was grateful for it: I’d had quite a bit of wine with dinner on Friday night, but had to run on Saturday morning because on Sunday I was taking my eldest to the Eagles/Cowboys game.

Virtual London Marathon 12/17

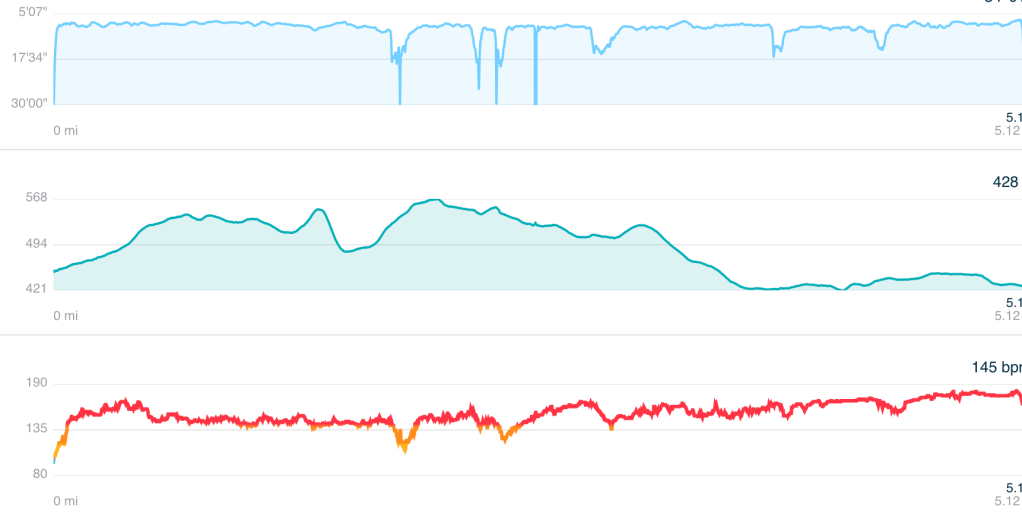

On this last weekend before the holidays, with my kids partying at their mom’s and my housemate out of town on a cruise, I was bored and starting to feel a bit stir crazy. I decided I’d run a marathon on my treadmill, picking 2021 London with Casey Gilbert. Unfortunately, the race was broken up into segments, so each time I had to switch to the next segment ended up being an “aid station” where I’d refill my water bottle or grab another stroopwafel.

The first half went great– I ran at a constant pace and finished in 1:55, feeling good and ready to keep going; my relatively slow pace kept my heart rate down. I finished the first twenty miles in a respectable 3:04:30, starting to worry that finishing in under 4 hours was going to be tough, but achievable. Unfortunately, things fell apart in miles 21 to 25, and my pace dropped dramatically; even though my heart rate was well under control, my legs were tired and I was beat. I rallied for the final three quarters of a mile back to 7mph, finishing with a somewhat disappointing but perhaps unsurprising 4:20:10.

Still, I’m proud of this race– while it was undoubtably much easier on the body than a real-world marathon, it was in no way easy and I never gave up.

After cooling down, I showered, ate, and caught “Love Actually” at the Alamo Drafthouse for the afternoon. My FitBit reported that I cracked 45000 steps for the day. My intake of three running stroopwafels, two bananas, a leftover fajita, a salad, a steak and vegetables probably did not cover the 4000+ calories I burned in the run.

Two days later, I’m still sore, although all three blisters have mostly faded away.

Early 2024 Races

I’ve got a good slate for early 2024, running the 3M Half again in January, the Galveston Half in February, and the Capitol 10K in April. I really hope to beat last year’s times in the Half Marathons (slow and steady ftw!), but don’t expect I’ll be able to beat my 2023 Cap10K time of 52:25.