While I have a day job, I’ve been moonlighting as a crimefighting superhero for almost twenty years. No, I’m not a billionaire who dons a rubber bat suit to beat up bad guys– I’m instead flagging phishing websites that try to steal money and personal information from the less tech-savvy among us.

I have had a Hotmail account for over twenty-five years now, and I get a LOT of phishing emails there– at least a few every day. This account turns out to be a great source of real-world threats– the bad guys are (unknowingly) prowling around a police station with lockpicks and crowbars.

Step 1: Report the Lure Email

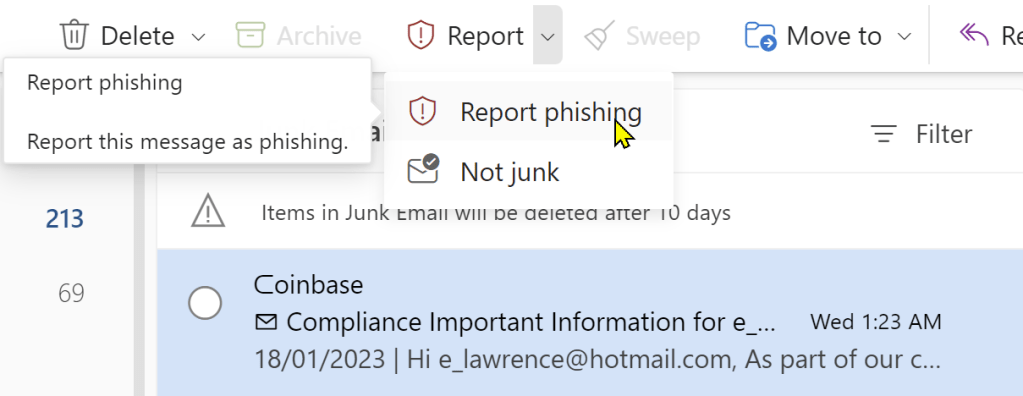

When I get a phishing email, I first forward it to Netcraft (scam@netcraft.com) and PhishTank. I copy the URL from the lure, then use the Report > Report Phishing option in Outlook to report the phish to Microsoft:

Step 2: Additional Research

If I have time, I’ll go look up the URL on URLScan.io and/or VirusTotal to see what they have to say, before loading it into my browser.

Step 3: Load & Report the Phishing Site

Now, most sources will instruct you to never click on a phishing link and this is, in general, great advice. The primary concern is that an attacker might not just be phishing– they might try to exploit a 0-day in your browser to compromise your PC. This is a legitimate concern, but there are ways to mitigate that risk: only use a fully-patched browser, use a Guest profile to mitigate the risk of ambient credential abuse, ensure that you’ve got Enhanced Security mode enabled to block JIT-reliant attacks, and if you’re very concerned, browse using Microsoft Defender AppGuard.

If the phishing site loads (and is not already down or blocked), I then report it to SmartScreen via the ... > Help and feedback > Report unsafe site menu command:

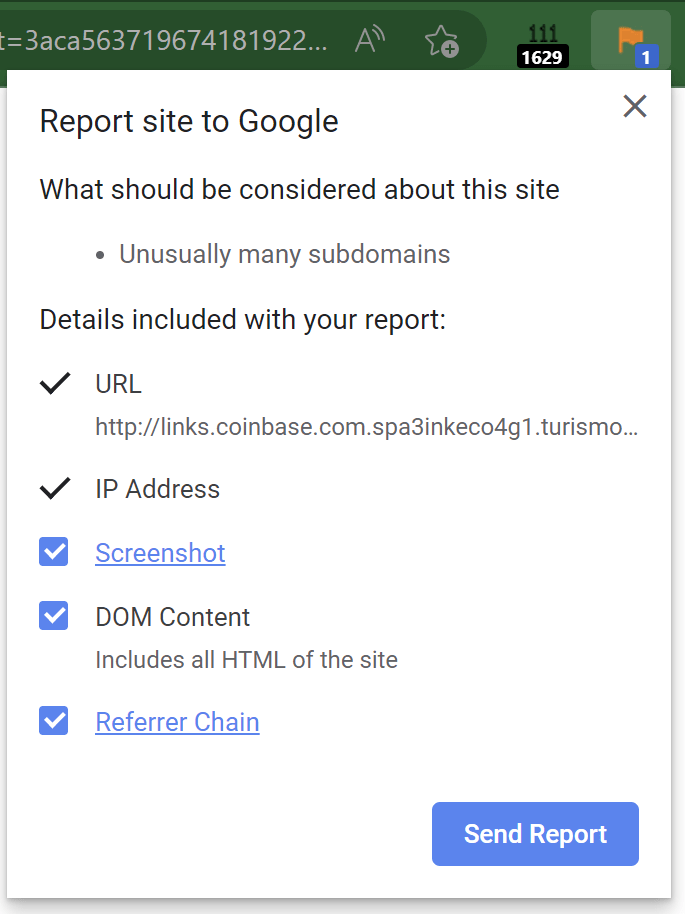

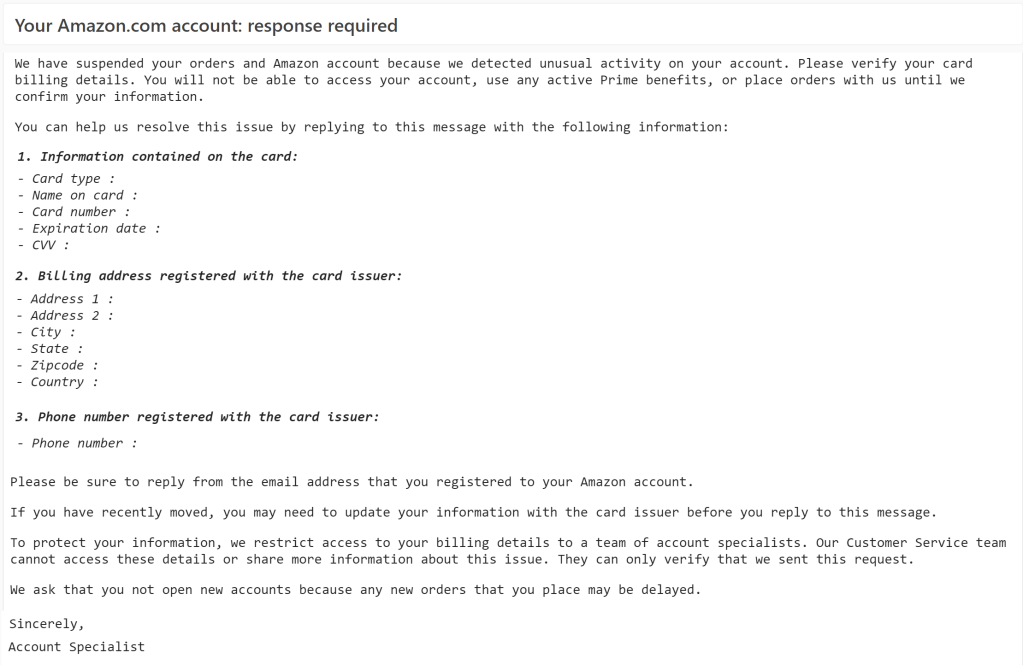

I also report the phishing site to Google’s Chrome/SafeBrowsing team using the Suspicious Site Reporter extension. This extension allows tech-savvy users to recognize suspicious signals for sites they visit and report malicious sites to SafeBrowsing in a single click:

Importantly, the report doesn’t just contain the malicious URL– it also contains information like the Referrer Chain (the list of URLs that caused the malicious page to load), and a Screenshot of the current page (useful for combatting cloaking).

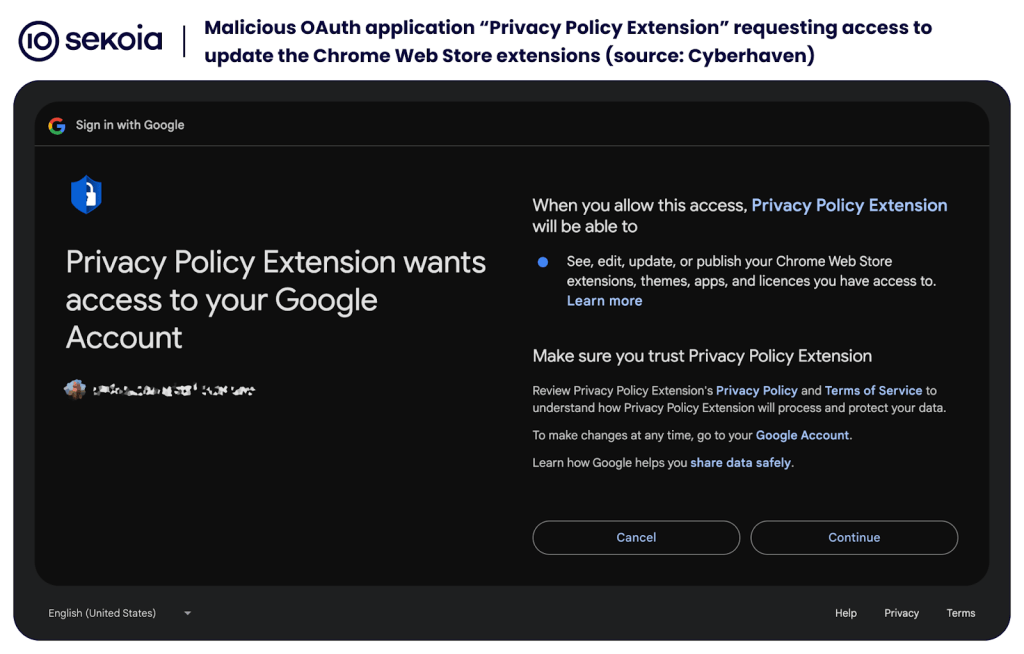

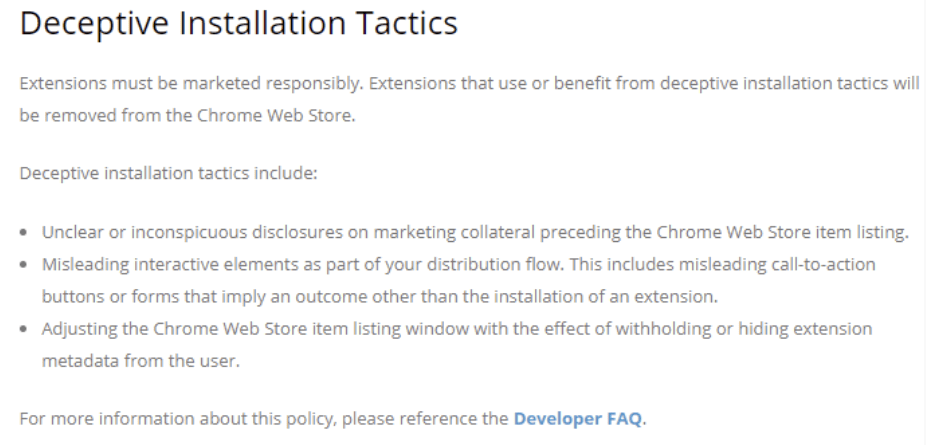

Attacker Technique: Cloaking from Graders

When a user reports a site as phishing, the report typically is sent to a human grader who evaluates the report to determine whether it’s legitimate. The grader typically will load the reported URL to see whether the target meets the criteria for phishing (e.g. is it asking for credentials or credit card numbers and impersonating a legitimate site?).

Phishers do not like it when their websites get blocked quickly.

A technique they use to keep their sites alive longer is named “cloaking.” This technique relies upon detecting that their site has been loaded not by a victim but instead by a grader, and if so, playing innocent– either by returning a generic 404, or by redirecting to some harmless page.

Phishers have many different strategies for detecting graders, including:

- recognizing known IP ranges (e.g. “If I’m being loaded from an IP block known to be used by Google or Microsoft Corp, I’m probably being graded“)

- single-use URLs (e.g. put a token in the URL and if that token is seen more than once, play innocent)

- geo-targeted phish (e.g. “If I’m phishing a UK bank, but the user’s IP is not in the UK, play innocent”)

- fingerprinting the user’s browser to determine how likely it is that it’s a potential victim

Some phishing sites are hosted unintentionally. In these cases, a server is owned by a legitimate company, but bad guys find a way to plant content on that server such that it is only shown to specific, targeted victims. For example, over a decade ago, I received report of an unblocked phishing webpage that was hosted by a hockey rink owner in the US Midwest. My investigation revealed that American visitors to the site would get a normal hockey team signup webpage. However, the phishing campaign was targeting a Russian bank, and if the user visited the site using a browser sending an Accept-Language: ru request header indicating that they spoke Russian, the site would instead serve phishing content. English-speaking graders would never be able to “see” the attack without knowing the “secret” that the site was using to decide whether to serve phishing content. Without screenshots of what a victim sees, graders have a very hard time deciding whether a given False Negative report is accurate or not.

Cloaking makes the job of a grader much harder– even if the reporter can go back to the grader with additional evidence, the delay in doing so could be hours, which is often the upper-limit of a phishing site’s lifetime anyway.

Additional Options

If you want to learn even more ways to combat phishing sites, check out the guide at GotPhish.com.

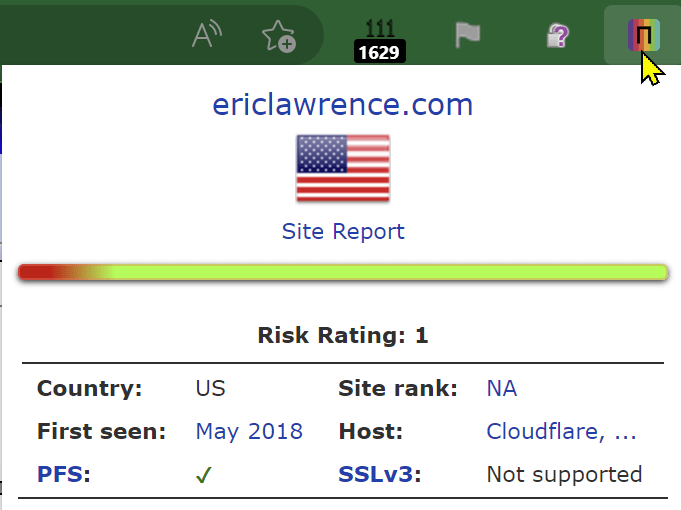

For example, Netcraft also offers a browser extension that shows data about the current website and allows easy reporting of phish:

If doing a good deed isn’t enough, Netcraft also offers some fun incentives for phishing reports— so far, I’ve collected the flash drive, mug, and t-shirt.

Tiered Defenses: Experts as Canaries

One criticism against adding advanced features to browsers to allow analysis or recognition of phishing sites is that the vast majority of users will not be able to make effective use of them. For instance, features like domain highlighting (showing the eTLD+1 in bold text) are meaningless to 99% of users.

But critically, such cues and signals like these are useful to experts, who can recognize the signs of a phish and “pull the alarm” to report phishing sites to SmartScreen, SafeBrowsing, and other threat intel services.

These threat reports, consumed by threat intelligence services, then scale up to “protect the herd.” Browsers’ blocking pages for known phish are demonstrably extremely effective, with high adherence even by novice users.

Making a Difference

Now, it’s easy to wonder whether or not any of this end-user reporting matters — there are millions of new phish a week — can reporting one make a difference?

Beyond my immediate answer (yes), I have personal evidence of the impact. One of my happiest memories of working on the IE team was when the SmartScreen team looked up how many potential victims my phish reports blocked. I shared with them my private reporter ID and they looked up my phishing reports in the backend, then cross-referenced how many phishing blocks resulted from those reports. The number was well into the thousands.

Beyond the immediate blocks, threat reports these days are also used by researchers to identify phishing toolkits and campaigns, and new techniques phishers are adopting. Threat reports are fed into AI/ML models and used to train automatic detection of future campaigns, making the life of phishers more difficult and less profitable.

Thanks for your help in protecting everyone!

-Eric