The vast majority of cyberthreats arrive via one of two related sources:

That means that by combining network-level sensors and throttles with threat intelligence (about attacker sites), security software can block a huge percentage of threats.

Protection Implementation

On Windows systems, that source of network threat information is commonly called SmartScreen, and support for querying it is integrated directly into the Microsoft Edge browser. Direct integration of SmartScreen into Edge means that the security software can see the full target URL and avoid the loss of fidelity incurred by HTTPS encryption and other browser network-privacy changes.

SmartScreen’s integration with Microsoft Edge is designed to evaluate reputation for top-level and subframe navigation URLs only, and does not inspect sub-resource URLs triggered within a webpage. SmartScreen’s threat intelligence data targets socially-engineered phishing, malware, and techscam sites, and blocking frames is sufficient for this task. Limiting reputation checks to web frames and downloads improves performance.

When an enterprise deploys Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE), they unlock the ability to extend network protections to all processes using a WFP sensor/throttle that watches for connection establishment and then checks the reputation of the IP and hostname of the target site.

For performance reasons (Network Protection applies to connections much more broadly than just browser-based navigations), Network Protection first checks the target information with a frequently-updated bloom filter on the client. Only if there’s a hit against the filter is the online reputation service checked.

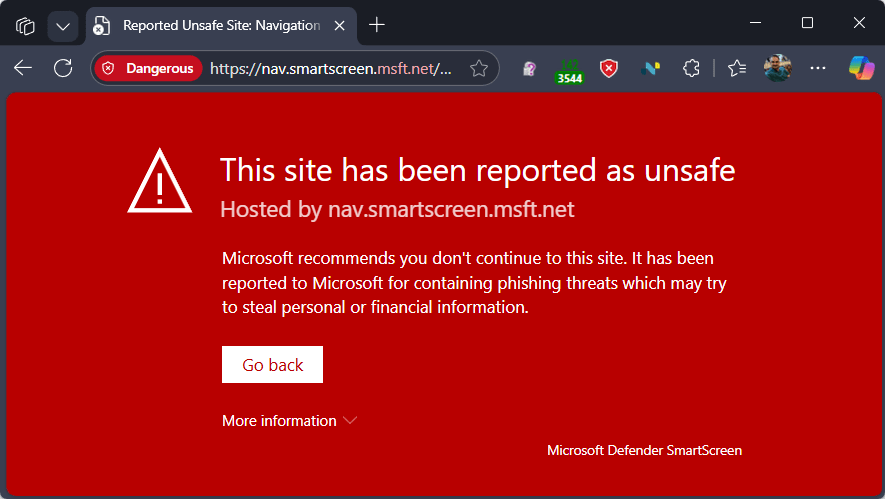

In both the Edge SmartScreen case and the Network Protection case, if the online reputation service indicates that the target site is disreputable (phishing, malware, techscam, attacker command-and-control) or unwanted (custom indicators, MDCA, Web Category Filtering), the connection will be blocked.

Debugging Edge SmartScreen

Within Edge, the Security Diagnostics page (edge://security-diagnostics/) offers a bit of information about the current SmartScreen configuration. Reputation checks are sent directly through Edge’s own network stack (just like web traffic) which means you can easily observe the requests simply by starting Fiddler (or you can capture NetLogs).

The service URL will depend upon whether the device is a consumer device or an MDE-onboarded. Onboarded devices will target a geography-specific hostname– in my case, unitedstates.smartscreen.microsoft.com:

The JSON-formatted communication is quite readable. A request payload describes the in-progress navigation, and the response payload from the service supplies the verdict of the reputation check:

For a device that is onboarded to MDE, the request’s identity\device\enterprise node contains an organizationId and senseId. These identifiers allow the service to go beyond SmartScreen web protection and also block or allow sites based on security admin-configured Custom Indicators, Web Category Filtering, MDCA blocking, etc. The identifiers can be found locally in the Windows registry under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows Advanced Threat Protection.

In the request, the forceServiceDetermination flag indicates whether the client was forced to send a reputation check because the WCF feature is enabled for the device. When Web Category Filtering is enabled, requests must hit the web service even if the target sites are “safe” (e.g. Facebook) because a WCF policy may demand it (e.g. “Block social media”).

If the target site has a negative reputation, the response’s responseCategory value indicates why the site should be blocked.

The actions\cache node of the response allows the service to instruct the client component to cache a result to bypass subsequent requests. Blocks from SmartScreen in Edge are never cached, while blocks from the Network Protection filter are cached for a short period (to avoid hammering the web service in the event that an arbitrary client app has a retry-forever behavior or the like). To clear SmartScreen’s results cache, you can use browser’s Delete Browsing Data (Ctrl+Shift+Delete); deleting your history will instruct the SmartScreen client to also discard its cache.

Debugging Network Protection

In contrast to the simplicity of capturing Edge reputation checks, the component that performs reputation checks runs in a Windows service account and thus it will not automatically send traffic to Fiddler. To get it to send its traffic to Fiddler, set the WinHTTP Proxy setting from an Admin/Elevated command prompt:

netsh winhttp set proxy 127.0.0.1:8888 "<-loopback>"

(Don’t forget to undo this later using netsh winhttp reset proxy, or various things will fall down after you stop running Fiddler!)

Unlike Network Protection generally, Web Content Filtering applies only to browser processes, so traffic from processes like Fiddler.exe is not blocked. Thus, to debug issues with WCF while watching the traffic from the nissvc.exe process, you can start a browser instance that ignores the system proxy setting like so:

chrome.exe --proxy-server=direct:// https://example.com

When a page is blocked by Web Category Filtering, you’ll see the following page:

If you examine the response to the webservice call, you see that it’s $type=block with a responseCategory=CustomPolicy:

Unfortunately, there’s no indication in the response about what category the blocked site belonged to, although you could potentially look it up in the Security portal or get a hint from a 3rd party classification site.

In contrast, when a page is blocked due to a Custom Indicator, the blocking page is subtly different:

If you examine the response to the webservice call, you see that it’s $type=block with a responseCategory=CustomBlockList:

As you can see in the response, there’s an iocId field that indicates whether the block was targeting a DomainName or ipAddress, and specifically which one was matched.

Understanding Edge vs. Other Clients

On Windows, Network Protection’s integration into Windows Filtering Platform gives it the ability to monitor traffic for all browsers on the system. For browsers like Chrome and Firefox, that means it checks all network connections used by a browser both for navigation/downloads and to retrieve in-page resources (scripts, images, videos, etc).

Importantly, however, on Windows, Network Protection’s WFP filter ignores traffic from machine-wide Microsoft Edge browser installations (e.g. all channels except Edge Canary). In Edge, URL blocks are instead implemented using a Edge browser navigation throttle that calls into the SmartScreen web service. That service returns block verdicts for web threats (phishing, malware, techscams), as well as organizational blocks (WCF, Custom Indicators, MDCA) if configured by the enterprise. Today, Edge’s SmartScreen integration performs reputation checks only against navigation (top-level and subframe) URLs only, and does not check the URLs of subresources.

In contrast, on Mac, Network Protection filtering applies to Edge processes as well: blocks caused by SmartScreen threat intelligence are shown in Edge via a blocking page while blocks from Custom Indicators, Web Category Filtering, MDCA blocking, etc manifest as toast notifications.

Block Experience

TLS encryption used in HTTPS prevents the Network Protection client from injecting a meaningful blocking page into Chrome, Firefox, and other browsers. However, even for unencrypted HTTP, the filter just injects a synthetic HTTP/403 response code with no indication that Defender blocked the resource.

Instead, blocks from Network Protection are shown as Windows “Toast” Notifications:

In contrast, SmartScreen’s direct integration into Edge allows for a meaningful error page:

Troubleshooting Network Protection “Misses”

Because Network Protection relies upon network-level observation of traffic, and browsers are increasingly trying to prevent network-level observation of traffic destinations, the most common complaints of “Network Protection is not working” relate to these privacy features. Ensure that browser policies are set to disable QUIC and Encrypted Client Hello.

Ensure that your scenario actually entails a network request being made: URL changes handled by ServiceWorkers and via pushState don’t require hitting the network.

If your scenario is blocked in Edge but some sites are not blocked in Chrome or Firefox, look at a NetLog to determine if H/2 Connection Coalescing is in use or disable Firefox’s network.http.http2.coalesce-hostnames using about:config.

Ensure that Defender Network Protection is enabled and you do not have exclusions that apply to the target process.

Test Pages

A older test page for SmartScreen scenarios can be found here. Note that some of its tests are based on deprecated scenarios and no longer do anything.