This is the second post in my Kilimanjaro series. The index is here.

When I was initially thinking about signing up for a trek up Kilimanjaro, I had two major areas to think about: my fitness, and all of the stuff I’d need for the trip. I knew that even if I didn’t ultimately take the trek, investing in my fitness would be a great outcome. I also figured that researching, collecting, and breaking in gear would be a welcome diversion from thinking about work and loss, so it seemed like another good reason to take the trek vs. just running races locally or something.

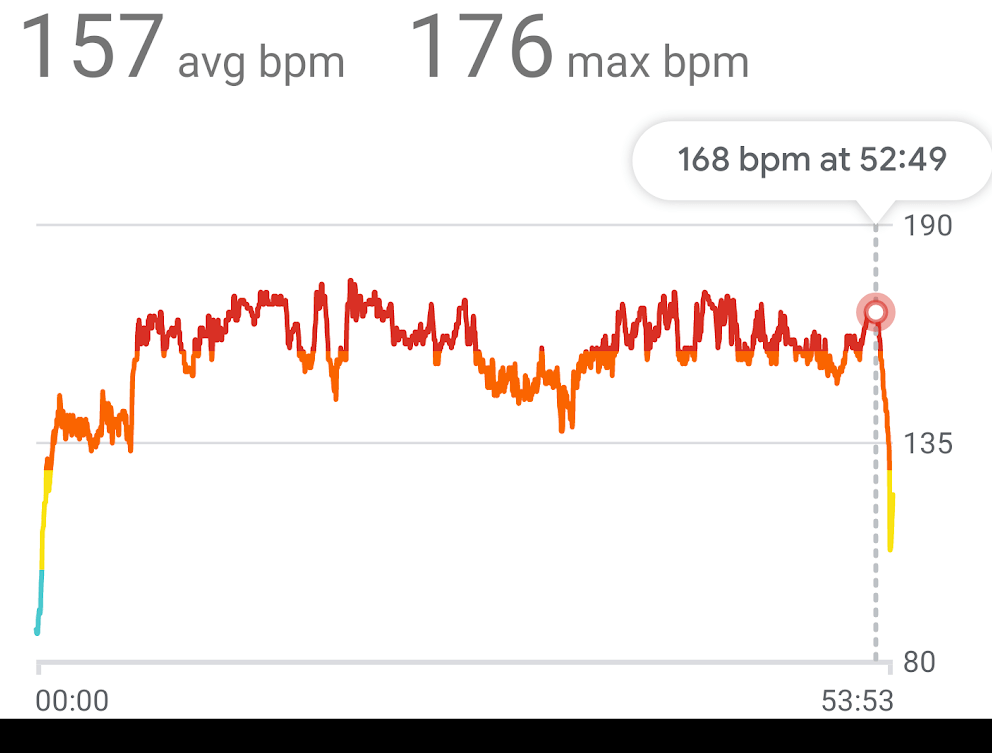

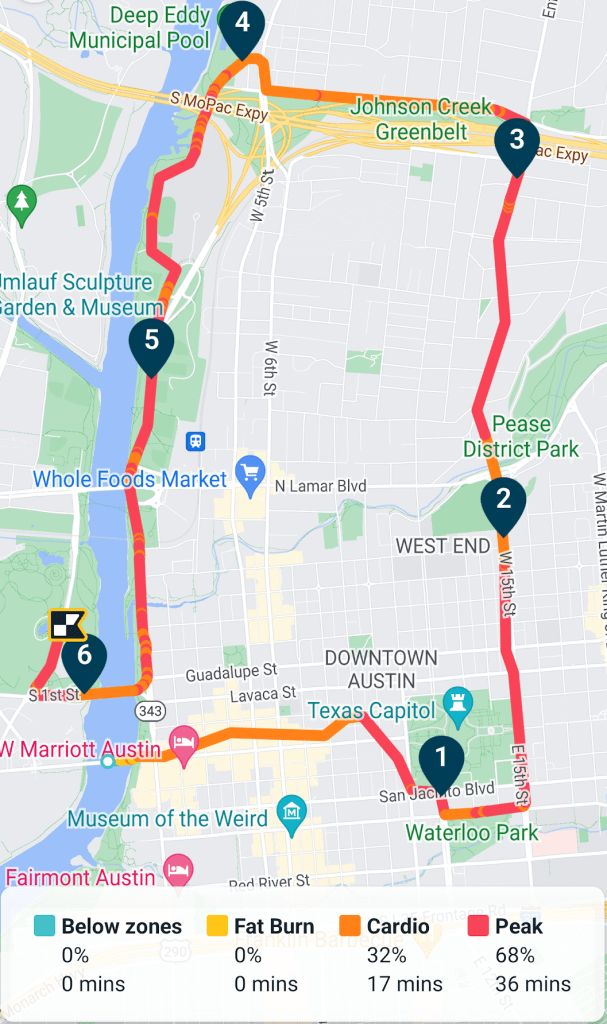

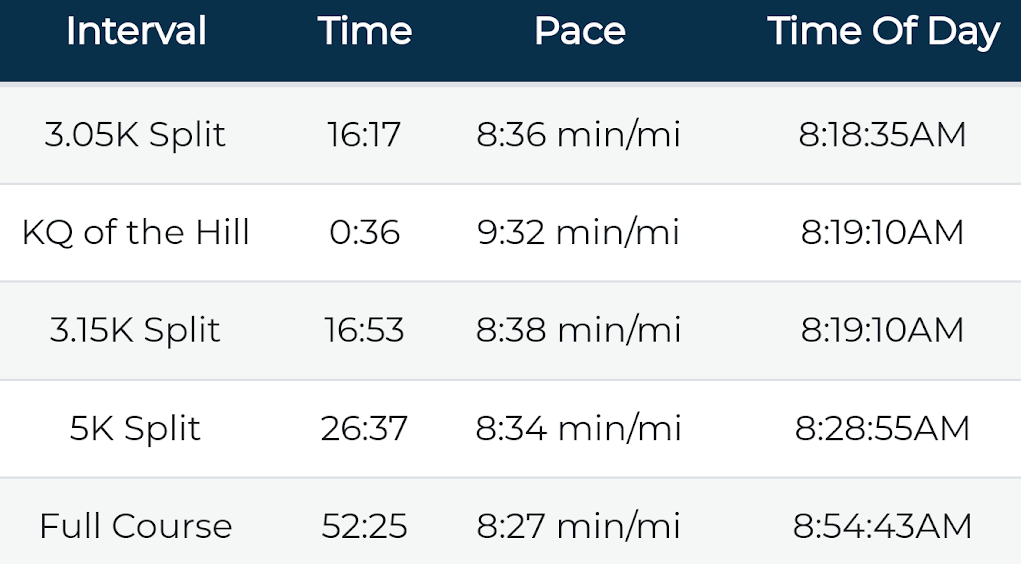

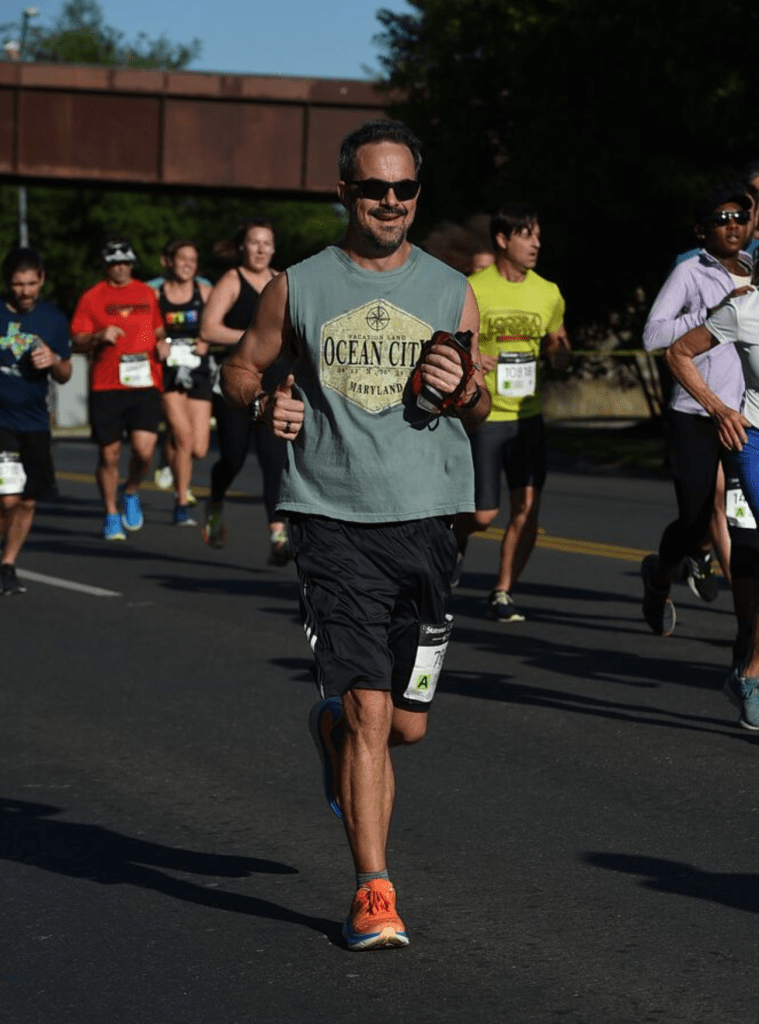

Over the next 18 months, I went from 240lbs to 190lbs (having bottomed out around 180) and dramatically improved my overall level of fitness, primarily by running. I’ve previously written a fair bit about my fitness journey as a part of my ProjectK series.

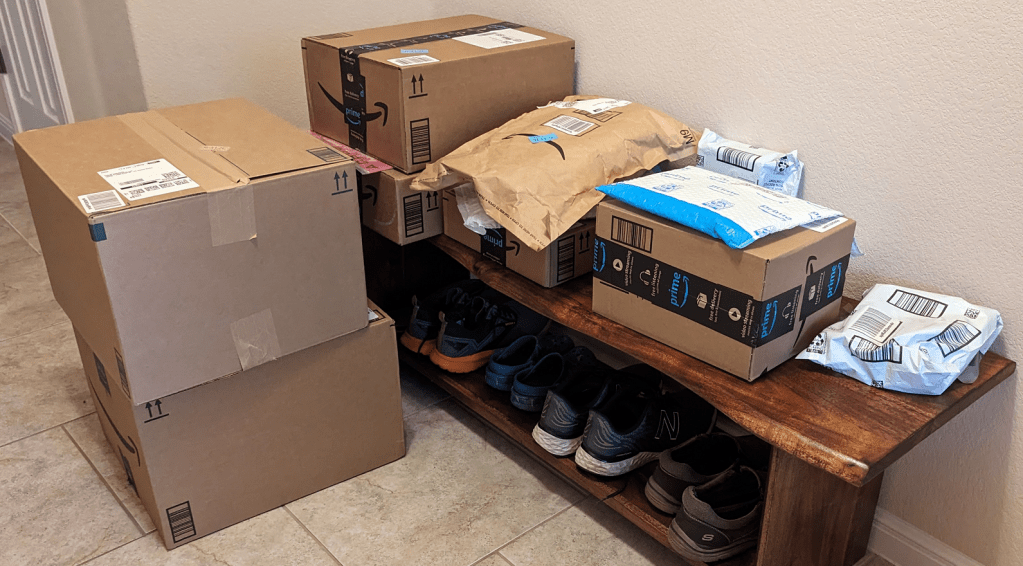

What I didn’t do for most of that time, however, is shop for gear. Early on, I bought and read a few books about Kilimanjaro treks, but I didn’t start buying most of my gear until late May, just about a month before my departure. In the final week, the Amazon driver was dropping a half dozen items at my house every day.

Trekking Kili takes a lot of gear, much of it cold-weather gear and not anything I have on hand after having lived in Texas for the last decade. Even things I thought I had (e.g. socks and underwear) needed to be replaced because it’s important to wear wicking clothing for long hikes. I’d never dreamed that I’d be spending $350 on socks and underwear for this trip!

One factor I didn’t anticipate is how good it feels to have and use the right tool for the job, and that turned out to be a big factor in how I felt about the trip. Where I had the right gear, I felt happy and confident. Where I didn’t, I felt regret and annoyance.

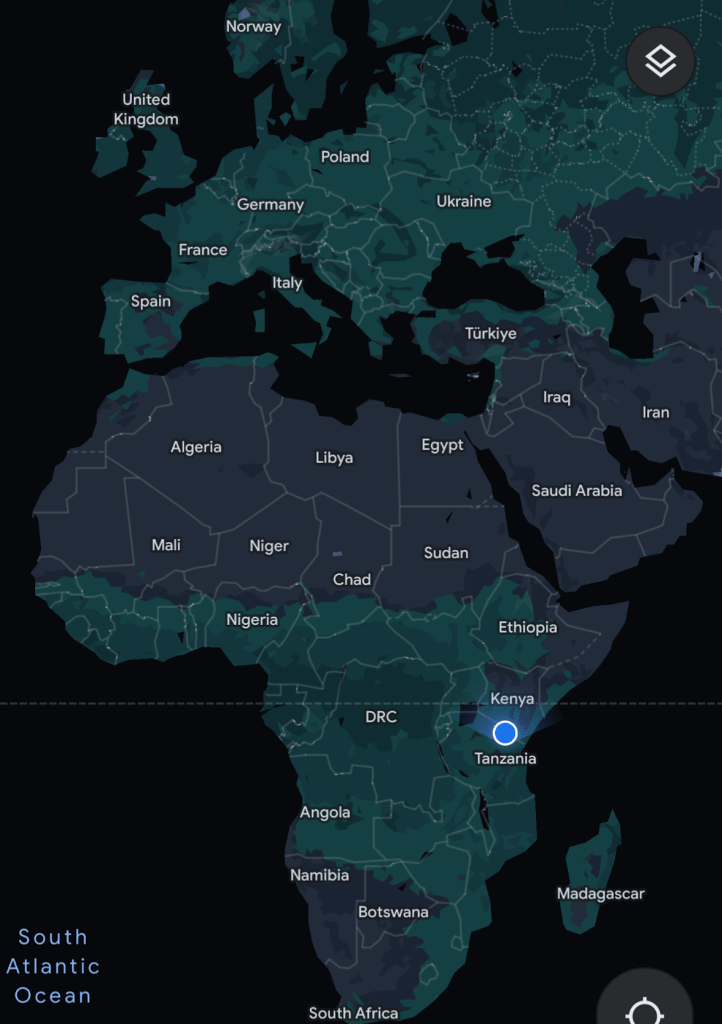

While we were told to plan on bringing a backpack of 30L or more, and a duffel of 140L or more, the true constraint turned out to be weight— porters are forbidden to carry duffels over 15 kilos (33 pounds), and weight accumulates fast. As I took off for Maryland to meet my brother on my way to Tanzania, my duffel was 40 pounds– and that was without any water in the bottles. 😬

In Maryland, I managed to drop just over two pounds (leaving behind clothes for the rest of my vacation after Tanzania, but adding some weight via consumables like protein bars and chocolate). At the bottom of Kili before the trek, I left behind two backpacks full of unneeded gear (power converters, extra clothing), starting the trek with a duffel at exactly the maximum allowed 33lbs.

Ultimately, it turned out that a fair number of my gear choices weren’t needed for the weather conditions of the trek– it wasn’t cold/wet enough to require much of the gear. Layering turned out to be key — on the summit day, I started with 5 layers on top and 3 on the bottom and it went great.

Our tour company provided a packing checklist, but it mostly doesn’t recommend any specific brands or styles and was often frustratingly ambiguous to someone who has spent as little time adventuring as I have.

The following is a list of gear I brought:

| montem Ultra Strong Trekking Poles | $74 | The top pick from Wirecutter, these were simple and worked great. I expected we’d only use poles for part of the hike, but in reality we used them for the entire trip except for a few brief sections of rock scrambling, e.g. up the Barranco Wall. |

| Salomon Quest 4 Gore-Tex Boots | $172 | Perhaps my best purchase for this trip. These were absurdly comfortable and I couldn’t help but feel like a confident trekker each time I put them on. I’d worried that I hadn’t broken them in enough (with just ~20 miles in walking around the neighborhood) but I didn’t get any blisters for the entire trek. While some of our team hiked in mid cuts, the fact that these were high ankle boots meant that no rocks/pebbles/etc ever got in my boots so I had no need for gaiters. |

| Boot Insoles | – | A gift, I didn’t end up using these except for the one day before the summit, where they didn’t seem to offer meaningful comfort beyond the already-comfortable boots. On summit day, they didn’t fit with my super-thick socks, so I took them out and didn’t use them again. |

| Merrell MOAB 2 Hiking Shoe | $90 | I bought these shortly before the trip with the intention of wearing them for the first few days of the trek and in camp. I didn’t end up bringing them after I realized that I was never going to make weight with them in my duffel. Ultimately, I think my full-size boots were more comfortable anyway. |

| My 5yo Crocs | – | I ended up wearing Crocs as my “camp shoes.” The traction was awful (and I should’ve brought fully enclosed ones given the dirt/dust), but they were light and worked okay. |

| DarnTough Merino Wool Socks | $150 /6 | Absurdly expensive but awesome. I could’ve easily done the whole hike with 3 or 4 pairs. I’d bought some liner socks to augment these (for warmth/sweat) but never bothered using them. |

| Smartwool Mountaineer Socks | $26 | These were my most “bulky” socks. I wore them to the summit, but they were no better than the DarnTough socks and I didn’t wear them again. |

| Qezer 0F Sleeping bag | $165 | Reasonably compact, and not too heavy. I didn’t end up using it in full “mummy” mode most nights, but it was warm enough anyway. |

| IFORREST Sleeping Pad | $69 | Pretty comfortable after learning that I’d over-inflated it on the first night. The side-rails on this pad were probably unnecessary and the overall weight-to-value ratio was probably questionable. |

| Eagle Creek Duffel | $116 | This was a great bag — super-sturdy and extremely water-resistant. At 133L, it was slightly smaller than the 140L+ bag we were told to bring, but I later noticed that a branded version of this bag is the only one that our tour company sells in their shop. |

| Frelaxy Dry sacks 3L, 5L, 10L, 15L, 20L | $32 | Very useful for keeping my duffel under control, although I probably should’ve gotten just two sizes (e.g. 5L and 15L) Well made, but expensive, and I wasn’t disciplined about what went where, so I spent a lot of time hunting for things. |

| Frelaxy Compression Sack 30L | $20 | I bought this to store dirty laundry. Ultimately the 30L size was much bigger than I needed given how much rewearing I was doing; I should’ve gotten the 18L version. |

| Osprey Talon Pack 33L | $165 | This bag came highly recommended and I liked it a bunch, although I probably could’ve gotten away with the 26L variant. I liked this one because it could hold my hydration reservoir and it had holders for my poles, but I did not end up using the latter. My brother carried the 22L version, which was too small. |

| Osprey Reservoir 2L | $38 | While a bit cumbersome to get into my pack, this worked pretty well and I ended up using it almost exclusively over the Nalgene bottles we carried. |

| Nalgene bottles | $63 /4 | We were told to bring four of these. I never used more than 2, and mostly didn’t use them at all in favor of my reservoir. That said, I did not do a good job with water on the trip and was technically dehydrated for most of it. |

| Osprey Raincover | $30 | A bit expensive and I ended up needing this only on the last day, but it helped a lot and worked great. |

| Canon Rebel T7 | $600 | While one tour company noted “Our guests have never regretted bringing a high quality DSLR“, bringing this camera was probably my biggest mistake. While it has a nice telephoto lens, the camera was big, heavy (several precious pounds), comparatively fragile, and its bulk and complexity meant that I usually didn’t have it out of the bag while hiking. It was useful on the mini-safari day because we were far from the zebras and giraffes, but the telephoto was mostly pointless while on the mountain. Worse, I got a spec of dirt on the sensor at some point, so many of my photos have a smudge at the top. :( I’d hoped to take some cool photos of the night sky, but I never got around to learning how to use the advanced modes for this camera and failed in this task. |

| Camera batteries and charger | $26 | I worried about my camera running out of battery, so I bought a USB charger and extra batteries. I needn’t have bothered– after taking over a thousand pictures, the Canon still claimed that its stock battery was full. |

| Google Pixel 6 Pro | – | I kept my Pixel powered-off for most of the trek to save battery, but it took some decent photos and was useful for texting once we got above the treeline and had intermittent service. My brother brought his new Samsung Galaxy S23 which took very good pictures, including an absolutely bonkers telephoto of the Uhuru Peak sign from the Stella Point sign (~3000 feet away). |

| iPad Mini 6 | – | I used this to watch movies on the flight over and many nights, my brother and I would watch an episode of the Simpsons in our tent before falling asleep. I never ran down the battery with light use. Probably not worth the weight/fragility given that I could’ve used my phone. |

| EINSKEY Sun Hat | $18 | Great buy. The sun on Kili is relentless and the cool temperatures mean that it’s easy to get burned without realizing it until too late. I wore this giant hat to minimize the need for sunscreen and neck protection. |

| ELLEWIN Folding baseball cap | $11 | Great buy. While I wore my big hat while hiking for sun protection, I wore this one pretty much non-stop otherwise. (I couldn’t wash my hair for 9 days 😬). I bought three more after coming home. |

| ALLWEI International Travel Adapter | $42 | This power adapter looked great on paper (flexible, lots of sockets, many plug adapters), but proved a total waste. Our hotel had USB charging ports, and this adapter didn’t work in most of the sockets (and I could never figure out why). |

| Power Bank 30,800mAh LCD Display Power Bank | $23 | I like that this power bank showed the remaining charge, but it didn’t seem to hold as much as claimed. |

| Anker PowerCore Slim 10000mAh Power Bank | $18 | This two year-old power bank powered our tent light for almost the entire trip. |

| BigBlue 28W Solar Panel | $71 | While I love solar, and this wasn’t totally useless, for the bulk and weight I’d’ve been better off leaving this behind in favor of an extra battery pack. In theory, I could hang this on my backpack while hiking with the included carabiners, but since I was doing that with my heavy camera bag it would’ve made my pack even more cumbersome. So instead I just set it up atop my tent when we made camp. I’ve been using this panel at the kids’ flag football practices/games — it sits nicely atop my shaded folding chair. |

| 6.5′ LED light strip | $11 | I brought these to light the tent and they worked well for that task. Amusingly, I also wore the light strip as a necklace on the final morning because I’d misplaced my headlamp. |

| Red LED Flashlight | $9 | Great – Good battery life, limited impact on night vision, lightweight and trouble-free. |

| Headlamp | – | A fancy gift from my brother, powered by either a rechargeable battery or AAA batteries. It seemed to work well, but I only used it twice — once on a trip to the toilet tent, and once for two hours on the pre-dawn summit morning. There ended up being a sorta funny story about that. |

| Pike Trail Gaiters | $32 | These worked okay, but proved redundant because I was wearing high-ankle boots. I didn’t wear them after the first day. Ultimately, I left them in Tanzania after the hike. |

| Ice Spikes | $16 | I was excited to use these “YakTrax” that strap spikes over the bottoms of boots for hiking on ice and snow. Alas, we never got closer than half a mile away from anything frozen (except a few puddles in the shade). Ultimately, I lamented wasting the weight and I left them in Tanzania after the hike. |

| IRONLACE – Paracord 550 Laces Type III Boot Laces 72-Inch | $8 | I really didn’t want to have a disaster where a boot lace broke, so I brought these. I didn’t ultimately need them, but they also would’ve been good for hanging laundry to dry, so I’m glad I had them. |

| Eddie Bauer 30L collapsible backback | $20 | I’ve used this for a bunch of trips and while it’s not super-light, it’s pretty compact and it’s a “good” non-flimsy backpack. I used this to hold the stuff that I was leaving at the bottom and not bringing up the mountain. |

| 4Monster collapsible 32L backpack | $29 | This backpack weighed almost nothing and took up almost no space. It was an excellent “leave behind” backpack but unlike the Eddie Bauer one, I wouldn’t want to actually use it as a backpack for long. |

| Smartwool Merino 250 Cuffed Beanie | $32 | Expensive, but comfortable and warm. |

| Merino Wool Balaclava | $29 | Many of our group wore these a lot, but I only wore mine during the summit descent to keep the dust out of my nose. A bit pricey for how little I used it. |

| MERIWOOL Merino Wool Thermal Pants | $64 | Midweight, I wore these every night after the first and they kept me comfortable. |

| MERIWOOL Long Sleeve Shirt | $64 | Midweight, I wore this every night and it kept me warm. I wouldn’t’ve survived the trip without this. |

| MRIGNT Heavyweight Long Johns Set for Extreme Cold | $46 | I didn’t end up wearing these, although they were soft and looked comfy/warm, if a bit bulky. Lacking any plausible scenario for wearing them after the trek back home in Texas, I’d planned to leave the set behind in Tanzania but accidentally took them home. Ah well. |

| BALEAF Hooded Shirt | $26 | This was a great hooded hiking shirt and I wore it for two or three days. I wish I’d brought more. The hood and thumbholed-sleeves were useful for times when I didn’t want to bother with sunscreen. |

| Under Armour Men’s Tech 2.0 ½ Zip Long Sleeve | $39 /2 | These were light and comfortable, although they didn’t have hoods, and I preferred the Baleaf shirt overall. |

| Columbia Tamiami II Shortsleeved Shirt | $36 | This was my most “safari” looking shirt and I like how it looked. That said, I ended up wearing long-sleeves for most of the trip for sun protection. |

| 5 Pack Men’s Active Quick Dry Crew Neck T Shirts | $43 /5 | Cheap, comfortable and nice looking. I didn’t wear them on the trek often due to the short sleeves, but I wore on the rest of my vacation. |

| BAMBOO COOL Men’s Underwear boxer briefs | $77 /8 | Great. I wore these almost every day. |

| adidas Boxer Briefs | $46 /6 | I bought a bunch of these and they were okay. |

| Smartwool Merino 150 Boxer Brief | $44 | By far the most expensive underwear I’ve ever owned. ($44/pair?!?!). They seemed nice, but I didn’t wear them. |

| Outdoor Ventures Rain Pants | $32 | I didn’t need these until the summit day, when they kept me warm as windpants pre-dawn, and then again on the last day as it drizzled. Ultimately, I really liked these pants (especially because they zipped from the bottom too, enabling taking them off without removing my boots). Alas, they got muddy on the last day and I somehow managed to either drop them or forgot them on the Land Rover. |

| North Face shell jacket | [est $120] | This was a very nice waterproof shell that weighed almost nothing but provided excellent protection from the rain and wind; I got it as team swag while at Microsoft but had never worn it before. It has a hood, zippered pockets, and zippered vents under the arms. |

Patagonia “Nano Puff” jacketSTY84212 | [est $220] | Also (expensive) Microsoft swag, this turned out to be one of the “MVP” pieces — not only was it a critical layer for warmth every night at dinner and on the summit day, it also folded into one of its own pockets and served as my pillow from night 2 onward. |

| Free Soldier Waterproof Hooded Military Tactical Jacket | $57 | I had expected this to be my “heavy” coat that I’d wear to the summit. In practice, it provided almost no warmth, and I left it behind when I left Tanzania. I liked how this jacket looked (and that I could put my 1991 Space Camp flight suit’s name badge on its velcro). Shame it wasn’t useful. |

| Free Soldier Fleece Cargo Hiking Pants | $47 | These were nice and would’ve made for excellent snow pants. However, it never was cold enough to require these while hiking, so I didn’t end up wearing them. |

| Wespornow Hiking Shorts | $43 /2 | These were great — light and sturdy. While it was too chilly to wear them as much as I expected, I’ve been wearing them non-stop since returning from the trek. |

| Free Soldier Hiking Pants | $42 | These were great — comfortable and sturdy, and I wore them a bunch. |

| Convertible Zip Off Safari Pants | $21 | These were fine hiking pants, although I ended up not needing their convertible feature at all. |

| Cooling Bandana | $16 | This was very high quality, but I didn’t use it. |

| Bandanas | $22 | I didn’t end up using any of these, although two women in my group ended up borrowing them to cover their hair or neck. |

| Outdoor Essentials Running Gloves | $13 | These were excellent — not too warm, but they kept my hands at a good temperature in the chilly weather. I wore them a bunch while hiking even when I wasn’t cold to keep the sun off my hands. |

| Tough Outdoors Winter Gloves | $22 | These heavy gloves seemed great, but the only time when I wanted to be wearing them (pre-dawn on summit day), they were packed in my duffel because I thought the light gloves would’ve been enough. Oops. |

| Fisher Space Pen | $33 | Crazy-expensive, but I used this for journaling every day and it did write at any angle and temperature. |

| Glasses | – | I ended up bringing a total of 4 pairs of glasses on the trip — three pairs of sunglasses and one pair of regular glasses. I wore one pair of sunglasses (wraparound RayBans) for almost the entire hike, and they worked well with my big hat which reduced the need for the recommended side-shields I didn’t have. I only brought extra sunglasses because I was afraid of breaking or losing a pair, but I certainly didn’t need three pairs. I brought my regular glasses for stargazing, but ultimately I didn’t really use them due to the cold weather at night. |

| Katadyn Micropur MP1 Purification Tablets | $13 | I brought these on a recommendation from a Kili hiking site. Ultimately, I only used them on the first day; the porters prepared our water via either boiling or purification and ultimately I decided that my belly problems were unlikely to be a result of the water (or that double-treating it would be worse). |

| Loperamide Hydrochloride Caplets, Anti-Diarrheal | $3 | I ended up taking one or two of these most days on the hike. |

| Malarone (Atovaquone – Proguanil) Anti-Malarial | $0 | This is apparently the anti-malarial BillG uses, which was good enough for me. I noticed no side-effects. I spent a lot of time thinking about mosquitos, but ultimately I think I only got one bite during the entire trip. |

| After Bite Itch Eraser stick | $11 /2 | I use these a lot in Texas, but didn’t need them on the trek. |

| Ben’s 30% DEET Repellent | $11 | We all used this for the first few days before we cleared the tree line. |

| Diamox (Acetazolamide) Altitude medication | $5 | Pretty much everyone on the trip took this to help with acclimatization at extreme altitude. I started taking half doses (1/2 pill twice a day) on the second or third day before ramping up to a full dose of two pills per day two days later. The most common side-effect from this medication is frequent urination which proved annoying during cold overnights. The second most common side-effect is tingling in your fingers and toes– I didn’t encounter this on the half dose, but it was immediate (and felt very odd!) once I started taking the full dose. It only lasted (or I only noticed) for fifteen minutes or so after each dose. |

| Advil | $8 | I think I may’ve taken two on the whole trip. |

| Dr. Scholl’s Moleskin Plus Padding Roll | $7 | Seemed like high-quality stuff, but no blisters meant no need for anti-blister tape. |

| DripDrop Hydration – Electrolyte Powder Packets | $28 /32 | I’ve used these when running and I like them. I brought them to try to encourage me to drink more water (and mask the kinda chemically taste of treated water). Ultimately, I only used four packets or so. |

| Neutrogena Ultra Sheer Sunscreen SPF 70 | $10 | I liked this. I used it on the backs of my hands, face, and neck when they weren’t covered by clothing. |

| Coppertone Pure and Simple Zinc Oxide Sunscreen Stick SPF 50 | $8 | Tiny and convenient, I used this mostly on my cheeks when I worried that my hat wasn’t providing enough coverage. |

| Royal SunFrog Tropical Lip Balm SPF 45 | $8 /2 | Great. I wore this long before I thought I needed it and it kept my lips (mostly) in good shape. I somehow ended up with some slight bleeding on the inside of my bottom lip, but it wasn’t a big deal. |

PURELL Hand Sanitizer Gel with aloe | $15 /6 | My hands have never been as dirty as they were on this trip. |

| Care Touch Hand Sanitizer Wipes | $11 | While pitched as more convenient than the Purell, I think I used one of the hundred I bought on the entire trip. |

| Body Wipes | $22 /50 | These were big and great. I ended up taking 30 to TZ and only using about 8 of them while trekking. (Eww. I didn’t really smell, I swear!) |

| Kleenex Tissues | My nose ran for basically the entire trek, but fortunately I’d heard about this and brought Kleenex. Ultimately, I did too good a job of conserving these and only used about one pack of the three I brought. | |

| JUKMO Quick Release Tactical Belt 1.5″ Nylon Web Hiking Belt with Heavy Duty Buckle | $21 | This was a cool belt, but cumbersome– you had to remove the buckle to take it off because it was too big for belt loops. I’d brought it for the heavy snow pants that I didn’t end up wearing. Ultimately, I loaned it to one of our luggage-delayed trekmates. |

| BIERDORF Diamond Waterproof Black Playing Cards | Brought but barely used. | |

| ATIFBOP Biodegradable Dog Poop Bags | Technically, we were supposed to pack out any TP we used on the trail, but fortunately I never had to resort to that. Still, having bags was useful for various reasons and I used about 10. | |

| Master Lock TSA Luggage Lock | $8 | I’ve never flown with a duffel before and I had nightmares of it coming open and spilling all of my gear in some foreign luggage transfer. |

| Coghlan’s Featherweight Mirror | $5 | Useful for seeing whether you’ve got your sunblock on right. Fun fact: my trekmates thought it was hilarious when I busted this out for the cinematographer when he was trying to fix his sunblock, and I think it’s what cemented my trail nickname: “REI.” |

| Smith & Wesson pocket knife | – | A gift, I didn’t use this often, but it came in handy a few times and it worked well. |

| Folding Steel Pocket Scissors | $7 | These seemed fine, but I didn’t end up using these at all, using the knife on the rare occasions when I needed to open something. |

| Sun Company Compass & Thermometer Carabiner | $14 | This was useful to have context on how cold it got overnight, but I didn’t use the compass at all. It was hard to read and photograph though, so I expect to use a different one next time. |

| Pulse Oximeter | $15 | I ended up owning two pulse oximeters (thanks, COVID-19!) and I brought one so I could check my own numbers in private if I ever wanted to. I only used mine a few times, IIRC, including at Stella Point and Uhuru Peak. |

| BOGI Microfiber Travel Sports Towel (40″x20″) | $8 | This seemed well-made, but given the low temps, I ended up using it just once. |

| Polepole: Training Guide for Kilimanjaro book | $30 | A nice training guide for Kili. Had I followed it, I’d probably have found the hike even easier. But just running like a madman for a year ended up working just fine. |

| The Call of Kilimanjaro book | $4 used | A nice and inspiring account of a trek |

| Kilimanjaro Diaries ebook | $6 | Oops. Never got around to reading this one before the trip. Reading it after, it turns out to be both pretty funny and one of the most informative/complete discussions of what the trip is actually like. |

| Lonely Planet Tanzania book | $21 | A nice guide, although coverage of Kili and the nearby area is only a small fraction of the book. |

| Swahili in One Week book | $8 | I wish I could say I’d made more of an effort in reading this but I didn’t do more than skim it. |

| Swimsuit | – | Swimsuit for the hotel pool |

| Giant pile of cash for tips | $1600 | American cash, mostly $20s. All bills must be unmarked, undamaged, and less than 10 years old. |

I probably brought a few more things that I’ve since forgotten, but I’ll add things as I remember.

What else did I wish I’d brought?

As you can see from the list above, I brought a bunch of things that turned out not to be very necessary. Looking back, what else do I wish I’d had?

- Caffeine-free tea, hot cider powder, etc – I ended up drinking a lot more hot drinks than I expected.

- Inflatable pillow – The Patagonia puffy was much better than nothing, but a small pillow would’ve been worth the weight/space.

- Collapsible solar lantern – The LED light strip was great and I liked it, but a collapsible solar lantern probably would’ve been simpler and more practical.

- Compact binoculars – I ended up using my camera’s long-lens for this purpose, but it offered only a narrow field of view and didn’t work as well as a pair of decent binoculars would have.

Next up — my daily journal and lots more photos.

-Eric