At WWDC 2025, Apple introduced an interesting new API, NEURLFilter, to respond to a key challenge we’ve talked about previously: the inherent conflict between privacy and security when trying to protect users against web threats. That conflict means that security filtering code usually cannot see a browser’s (app’s) fetched URLs to compare them against available threat intelligence and block malicious fetches. By supplying URLs directly to security software (a great idea!), the conflict between security and privacy need not be so stark.

Their presentation about the tech provides a nice explanation of how the API is designed to ensure that the filter can block malicious URLs without visibility into either the URL or where (e.g. IP) the client is coming from.

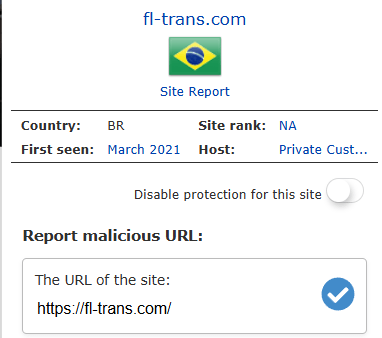

At a high-level, the design is generally similar to that of Google SafeBrowsing or Defender’s Network Protection — a clientside bloom filter of “known bad” URLs is consulted to see whether the URL being loaded is known bad. If the filter misses, then the fetch is immediately allowed (bloom filters never false positive). If the bloom filter indicates a hit, then a request to an online reputation service is made to get a final verdict.

Privacy Rules

Now, here’s where the details start to vary from other implementations: Apple’s API sends the reputation request to an Oblivious HTTP relay to “hide” the client’s network location from the filtering vendor. Homomorphic encryption is used to perform a “Private Information Retrieval” to determine whether the URL is in the service-side block database without the service actually being able to “see” that URL.

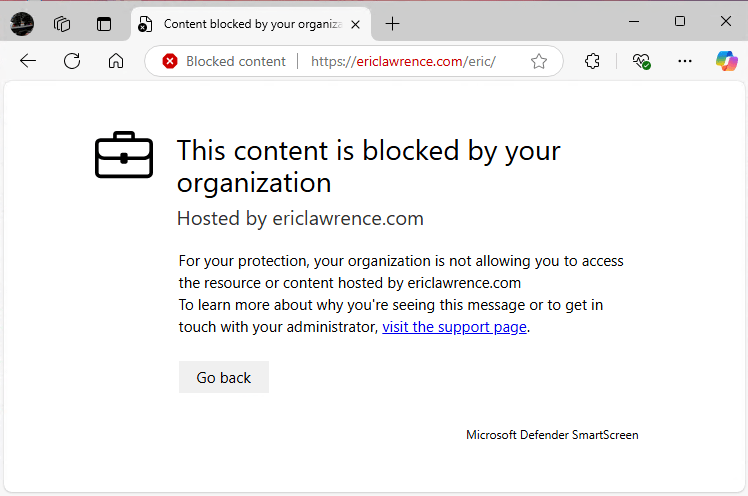

Filtering requests are sent automatically by WebKit and Apple’s native URLSession API. Browsers that are not built on Apple’s HTTPS fetchers can participate by calling an explicit API:

Neat, right? Well, yes, it’s very cool.

Is it perfect for use in every product? No.

Limitations

Inherent in the system design is the fact that Apple has baked its security/privacy tradeoffs into the design without allowing overrides. Here are some limitations that may cause filtering vendors trouble:

- Reputation checks can no longer discover new URLs that might represent unblocked threats, or use lookups to prioritize security rescans for high-volume URLs.

- There does not seem to be any mechanism to control which components of a URL are evaluated, such that things like rollups can be controlled.

- Reputation services cannot have rules that evaluate only certain portions of a URL (e.g. if an campaign is run across many domains with a specific pattern in the path or query).

- There does not appear to be any mechanism to submit additional contextual information (e.g. redirect URLs, IP addresses) nor any way to programmatically weight it on the service side (to provide resiliency against cloaking).

- There does not appear to be any mechanism which would allow for non-Internet operation (e.g. within a sovereign cloud), or to ensure that reputation traffic flows through only a specific geography.

- There’s no mechanism for the service to return a non-binary verdict (e.g. “Warn and allow override” or “Run aggressive client heuristics”).

- When a block occurs in an Apple client, there is no mechanism to allow the extension to participate in a feedback experience (e.g. “Report false positive to service”).

- There’s no apparent mechanism to determine which client device has performed a reputation check (allowing a Security Operations Center to investigate any potential compromise).

- The fastest-allowed Bloom filter update latency is 45 minutes.

Apple’s position is that “Privacy is a fundamental human right” which is an absolutely noble position to hold. However, the counterpoint is that the most fundamental violation of a computer user’s privacy occurs upon phishing theft of their passwords or deployment of malware that steals their local files. Engineering is all about tradeoffs, and in this API, Apple controls the tradeoffs.

Verdict?

Do the limitations above mean that Apple’s API is “bad”? Absolutely not. It’s a brilliantly-designed, powerful privacy-preserving API for a great many use-cases. If I were installing, say, Parental Controls software on my child’s Mac, it’s absolutely the API that I would want to see used by the vendor.

You can learn more about Apple’s new API in the NEURLFilterManager documentation.

-Eric

PS: I’ve asked the Chromium folks whether they plan to call this API.