tl;dr: As of last week, I am now a Software Engineer at Microsoft.

My path to becoming a Program Manager at Microsoft was both unforeseen (by me) and entirely conventional. Until my early teens, my plan was to be this guy:

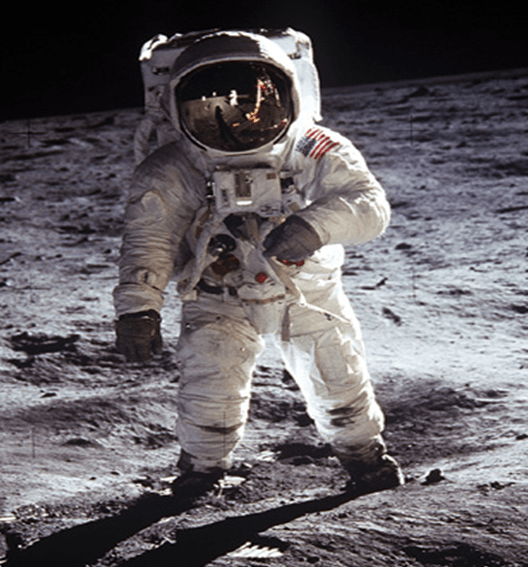

I went to Space Camp and Space Academy, and spent years devouring endless books about NASA history, space flight, and jet planes. I spent hours “playing” on a realistic (not graphically, but in terms of slow pacing and technical accuracy) Space Shuttle simulator, until I could land the shuttle on instruments alone.

Over time, however, three factors conspired to change my course.

- First was my realization that my few peers interested in space flight were all interested in space — stars and planets and the science, while I really only cared about the technology of getting there and surviving.

- Second was the discovery of a Catch-22: While astronaut pilots don’t have to have perfect vision, they were required to have thousands of hours of experience flying jets, which practically required being a military jet pilot, which did require perfect uncorrected vision. My distance vision has been ~20/40 for most of my life.

- Finally, I’d started getting more and more interested in playing around with computers. I began writing “choose-your-own adventure” games in GW-BASIC starting around age 8 or so, and continued coding in school on Apple II (AppleBasic) and PCs (Logo, Pascal).

Shortly after my 15th birthday, I spent a full summer job’s earnings (~$3000 at $4.75/hr) on my first personal PC (Comtrade Pentium 90 PC with 8 megs of RAM, 730mb HDD, 4X CDROM, 15.7″ monitor, bought over the telephone from an ad in Computer Shopper magazine) and I started writing apps in Turbo Pascal, VB3 (bought for $50 on 5.25″ floppies at the annual “Computer show” at the Frederick Fairgrounds), and eventually Delphi 1 ($100 at Babbages in the mall). By my late teens, I was spending ten or more (sometimes much more) hours a week writing code, and after my senior year, I got my first programming job building custom Windows apps in Delphi for a small development shop at almost 4x minimum wage.

After high school, I majored in Computer Science at the University of Maryland, and while I largely didn’t like it (too much theory, too little practice), I had already seen that software development was a pretty solid career choice. In my sophomore year, on a whim (with the promise of free pizza) I went to a Microsoft recruiting talk on campus delivered by Philip Su, a recent University of Maryland graduate who had joined Microsoft as a developer. Philip was a school legend, having written UMD’s web-based course planning system (a CGI written in C++ talking to the mainframe and spitting out HTML) that allowed you to specify constraints like “I need this many credits, these specific classes, and otherwise do not want to attend class before 11am on any day.” After Philip’s awesome talk, I went from being mildly interested in Microsoft to very excited at the prospect of getting an internship. I dropped off my resume, chatted briefly with Philip, and crossed my fingers.

I got a callback for a short interview at the campus career center a short time later. I didn’t really know what to expect, but figured my best bet was to show off the code I’d built so far. I put together a small binder of screenshots and explanations of tools I’d built in Delphi, including SlickRun, DigitalMC, and Logbook, a journaling program. Each of these was a “scratch my own itch” type of app where my goal was to use technology to solve a problem. In each app, I tried to build cool features, not implement fancy algorithms from scratch. Digital MC used several different libraries (text-to-speech, MP3 playback) and Logbook used an existing database engine.

My campus interviewer was a Microsoft developer in his early thirties (in hindsight, he may well have been younger) who looked a bit weary after a morning full of 15 minute interviews. After quick introductions, he asked which of the engineering roles I’d be most interested in applying for.

I told him that I thought I’d be a fine fit for any of the roles, although I was most interested in the SDE (Software Development Engineer) and PM (Program Manager) roles, and was interested in what he thought. I handed over the binder and walked him through the projects I’d built— as I explained SlickRun, his eyes lit up and he was clearly excited about it. “Have you ever shown this to Microsoft?” he asked excitedly. “I guess I just did?” I replied, wondering what exactly he meant— it wasn’t as if Microsoft toured the country looking for interesting bits of code. I asked him for advice on whether I should go for the PM or SDE role and he noted that Microsoft was looking for SDE interns with experience building 5000 line C and C++ programs. At that point, I’d built several large applications, but all were in Delphi’s Object Pascal. The only C and C++ I’d written was for class projects, and none of those had yet cracked a thousand lines. This made the decision easy— I’d submit my resume as a PM-candidate, a decision with far-ranging and long-lasting consequences. Not long after, I flew to Redmond for a day of on-site interviews with two teams in Office and got offers from both.

During my first Office summer internship in 1999, I ramped up on a new technology (devouring the first books on XML), wrote up competitive reports on the first web-based collaboration software, and played with the nascent API for our team’s “Office Web Server (OWS)” product (eventually renamed SharePoint Team Services). I attended a bunch of training classes, read a bunch of product specs, read a pile of usability books, and generally immersed myself in learning what it meant to be a Program Manager at Microsoft. At the time, the role was hand-wavingly defined as “The person who does everything but code and test.” Qualifications were similarly open, with recruiters told to look for candidates with “A passion for using technology to solve problems.”

I returned to the same team the following summer– by this point, the product was in much more defined form, and I was paired with an Intern Developer and Intern Tester (a “feature trio”) to build a feature. Over the course of the summer, I learned that the primary tasks for most PMs were writing feature design specifications, shepherding them through implementation, triaging bugs found in the implementation, and getting ready for release.

SharePoint was a product based on the idea of Lists (lists of documents, lists of links, lists of contacts, etc) and my intern trio was tasked with adding a feature whereby a SharePoint user could create a list based on pre-built templates with appropriate fields (e.g. the Contact list would have fields for email address, phone number, office address, etc, etc). I wrote the spec for how the feature should look, and for the packaging format that would define each template. I also wrote (in Delphi) a generator/packager app to allow a content team (initially me) to build template files in the correct format. Our dev intern (Brandon) wrote the C++ code that would run inside SharePoint to ingest the package and call the appropriate APIs to create the new list. Our tester (Matt?) made sure it all worked. We finished our feature before the 12 week internship was up, and I considered it an unqualified success.

Offered a full-time job after the internship, I went back to Redmond for a perfunctory day of interviews with the team and was greatly annoyed to learn that our internship’s Template feature had been unceremoniously cut from the release. That outcome, as well as the lack of challenging interview questions from the team, led to me surprising everyone (including myself) by deciding to switch teams. I chose to join the Office Update team, then responsible for all of the Office web sites.

During my senior year back at UMD, I had a work/study internship as a web developer at The Motley Fool, and wrote a primitive OS in C++ for CS412. After finally crossing that “5000 lines of C++” threshold that Microsoft was looking for, I still didn’t seriously consider moving over to SDE. I was already “in” as a PM, and from my internship, it felt like there was a greater opportunity for impact as a PM vs. SDE — most of the SDE interns only owned a tiny piece of a product because it took a ton of work (ensuring accessibility, globalization, localization, performance, security, etc, etc) to deliver that tiny piece. As a PM, I’d be able to direct the work of several developers and focus on maximizing the value of their work for our users. To be honest, being a 21 year-old PM felt a bit like using a “cheat code”– when I’d interviewed at IBM they were super-confused at my resume because at Big Blue, a PM was a grizzled developer who’d “moved up” after a decade of coding. But at Microsoft, I’d get to start there.

The Office Update team went through a reorg before I started, so in June 2001, I started on the Office Assistance and Worldwide Services (AWS) team, as the PM owner of the clipart website and as the team’s Security PM. I spent the three years on Office writing feature specs, triaging bugs, and generally doing “everything but writing code.”

Except… well, I wrote a lot of code. I wrote “Rip Art Gallery,” a tool for abusing the Office website’s API to download clipart without requiring an Office app, and wrote a proof-of-concept ActiveX control for a new feature. I wrote the Clip of the Day tool, to allow Content team to generate the XML manifests of which clip to feature in which locales, on each day for the upcoming months. I wrote webserver log analysis tools. I wrote TamperIE, a tool designed to exploit websites that failed to validate request data, and accidentally leaked it to the world.

Outside of work, I wrote a popular popup blocker (and a less popular one), continued to update SlickRun, maintained DigitalMC and Logbook, created MezerTools, wrote some simple IE Extensions, wrote some simple Delphi libraries (including two for CD-R burning), started building the Fiddler Web Debugger and Meddler, and otherwise acted like a developer. Nearly all of my code was written in Delphi, C#, or JavaScript, with my only C++ development being tiny tweaks to the Internet JunkBuster Proxy to convert it into a bare-bones HTTP traffic logger.

Every few months, my manager would ask “Are you sure you’re not a developer?” and I would demur and explain that I simply loved being a PM. Privately, I also worried that I might lose interest in my many side projects if I started writing code for work.

By the fall of 2004, I decided to move on from Office and join the Internet Explorer team. The newly reconstituted browser team was rapidly growing, and they were hungrier for SDEs than PMs, so the devs on my interview loop were eager to get me to jump disciplines. Unwilling to change both teams and roles at the same time, I remained a PM. Internet Explorer offered more opportunity to become a technical PM though, and I rapidly leaned into it, owning both the new consolidated URL (CURL) class as well as much of the networking and network security areas.

I also immediately embarked upon my barely secret mission — to figure out what bugs in Internet Explorer were responsible for the problem where the Office Clip-of-the-Day wasn’t reliably changing every day. (My futile queries to the skeleton IE team were how I encountered the “Want to change the world? Join the new IE team today” recruiting pitch). With my newly granted source code access permissions, I printed out the code for the WinINET network stack and read it at night with a red pen in hand. While I was not a C++ developer, I was reasonably competent as a C++ reader, and I flagged nearly a hundred bugs, including six different issues that would’ve caused the Clip-of-the-Day to fail to change.

When I’d first joined the IE team, my manager suggested that I find someone else to take over development of Fiddler, because I’d “be too busy.” “We’ll see” I replied, cockily thinking “Your entire test team are all going to be running Fiddler pretty soon.” I was right. I continued to spend tens of hours a week writing Fiddler code, late into the night and on weekends, and its audience grew and grew. In 2007, it won the Engineering Excellence award and I got a handshake from Bill Gates and $5000 to spend on a morale event. While Fiddler dominated my coding time, I still maintained SlickRun and built a few one-off utilities, including an ActiveX control that earned me a $500 steak dinner with friends at Daniel’s Broiler, and an IE extension that won me $3000 in furniture from Pottery Barn and Crate&Barrel. Perhaps my most lucrative win came when a new hire was assigned to “officially productize” a simple web app I’d written to generate IE Search Providers; we started dating and were married three years later.

After several years languishing in the PM2 level band, I finally broke into the Senior PM band on the recognition of my technical contributions. I could go toe-to-toe with the developers in triage conversations, often knowing the code as well as they did, and I built many reduced reproductions for bugs, sometimes explaining exactly what lines of code were at fault.

Toward the end of IE9, I was deeply interested in improving network performance, but I lamented that the dev team couldn’t muster the resources to fix a dozen performance bugs in the network cache code. As I explained the changes needed and how impactful they could be, one of our developers (Ed Praitis) listened thoughtfully and then quietly noted: “It seems like you understand this stuff pretty well. Why don’t you just fix it yourself?”

I chuckled until I saw he was serious. “But I’m a PM!” I protested, “we don’t check-in code. At least, nothing like this.”

“I’ll review it for you if you want,” he offered. And this was just the push I needed. Within a few weeks, I checked in my fixes, and it was the work I was most proud of in over a decade at the company… helping save hundreds of millions of users untold billions of seconds in downloading pages. Around that time, I also offered up a small change to the WinINET code to make it work better with Fiddler, and to my surprise (and amusement) that team accepted it.

After a decade, I’d started to get a bit burned out on the PM role, and fresh off the excitement of landing actual shipping product code, I pondered whether I could take the pay hit of down-leveling to become a junior SDE. Instead, team turnover intervened, and I became a PM Lead, with my four reports owning IE’s Security, Privacy, Reliability, Telemetry, Extensibility, and Process Model features. Despite my rather untraditional PM background, I was, apparently, going to continue my career in a PM Leadership role.

And then, I got an email. A developer tools company was interested in acquiring Fiddler, and I, looking at a full plate with “a real job,” a new wife, and plans for a baby within a few years, decided that the booming Fiddler project deserved a full-time team. I got deep into negotiations to sell Fiddler outright when a phone call from a second interested party threw everything aside. Telerik not only wanted to buy Fiddler, they also wanted me to come work on Fiddler for them in Austin, Texas. The financial terms were more generous, and the lower cost-of-living in Texas meant that we’d only need one income. After a blissful March visit and negotiations over the summer, I signed the papers and my wife and I both gave notice at Microsoft.

At Telerik, my job title in the address book fluctuated around as the company grew and evolved and I never paid it much attention– whether it was “Principal Software Engineer” or “Product Manager” or something else, I considered myself “Fiddler Product Owner” and I did all the jobs, from coding to user research to support to design to testing. Once in a while, I’d consult on Telerik’s other products, but I never wrote any meaningful code for them.

Alas, after two years and a big pre-IPO layoff of nearly everyone else in the building, I was no longer feeling stable at Telerik and I applied for a Developer Advocate role on the Chrome Security team in 2015. Google is amazeballs at many things, but hiring is not one of them. I completed the Developer Advocate interview loop but their hiring committee came back and suggested that I should be a Technical Program Manager. I did a TPM interview loop, but their hiring committee came back and suggested I should be a Developer Advocate. The lead of Chrome Security decided to resolve the deadlock by hiring me as a Senior SWE (Software Engineer), for which she had sole authority. Since I’d be reporting directly to her, she assured me, my actual duties would be unchanged and my address book title would make no difference. With significant trepidation (I always worried about anything “off book”), I agreed.

I had a very strange ramp-up at Google, with paternity leave after my second son was born in week 2, and a subsequent long bout with pneumonia. Within a few months of starting, a reorganization meant that I’d now start reporting to a new manager. “My new boss knows that I’m not really a SWE and I’m really this special unicorn, right?!?” I asked my director, and was assured the answer was “Yes.” I then went to confirm with my new boss: “You know I’m not a SWE, right? I’ve only written like two files of C++ in the last fifteen years. I’m really this special unicorn DevAdvocate.” She responded “Well, um, I don’t actually have any special unicorn jobs on my team. I do have a SWE job, however, and you do have a Senior SWE title, so we should see if it’s a good fit, right?”

As a father of now two and provider for a single-income family, I didn’t see a lot of options. I looked into down-leveling so my skills matched my role, but Google HR indicated that wasn’t an option, both because they didn’t allow down-leveling and because they didn’t allow remote employees below the Senior level. I spent a total of two and a half years barely keeping my head above water, landing 94 changelists in Chromium and learning a ton. I joked without joking that I was the worst developer in Chrome. While there was much to admire about how Google builds products, I lamented the lack of Microsoft-style PMs and always wondered how much more efficient the team would’ve been with a proper complement of Program Managers.

In 2018, when I saw that one of my former direct reports was now a Group Program Manager at Microsoft, I asked for a job and was delighted to learn that remote work was now possible at the “new Microsoft.” I came back as a Principal Program Manager, and twice ended up acting as an interim lead for a few months as the team turned over. As a PM on the “Web Platform” and as one of the only Edge employees with any experience in Chromium, I got to remain hyper-technical, spending the majority of my time reading specs, guiding designs, explaining engineering systems, reading code, reducing repros, and root-causing problems.

As the team ramped up on Chromium, Microsoft as a whole began a journey to redefine the Program Management role, eventually splitting the role into Product Management (PdM) and Technical Program Management (TPM) to match Google. It was not a graceful process, and many of us felt a great deal of angst at the change. The 2012 book How Google Tests Software had presaged Microsoft’s earlier messy implosion of its Software Test Engineer role, and now it seemed that Microsoft was looking to continue its Googlification and eventually phase out the PM role entirely.

Throughout 2021, I found myself hunting for useful work to do. I spent almost a year as an “enterprise fixer”, landing 168 changelists in Chromium — most of them quite small, and targeted at unblocking enterprises from deploying the new Edge. I again pondered down-leveling to switch disciplines, with perhaps even higher stakes, having ceded half my net worth in a divorce and with the stock market suffering wild gyrations daily.

Finally, in 2022, I took a leap, leaving the Edge team to rejoin old friends and colleagues on the Microsoft Security team responsible for SmartScreen and other security features across products. I spent a few months ramping up into the new technologies, looking at active attacks, and reviewing the code the team has built so far. I kept the “Principal Product Manager” title as a placeholder, with the promise of a reclassification to “Architect” at some point in the future, a spiffy-sounding title that feels like a good fit to encompass the sorts of contributions I like to make.

In conversations with my lead last week, we agreed that “PM” was no longer a good fit for the work I’ll be doing in the coming years, so as of Friday, I’m now a “Principal SWE Manager.” While I don’t think any title has ever been a particularly good fit for the breadth of work I do, I’m excited to try this one on.

-Eric

PostScript: After six months as a SWE (including modernizing this code), I was given a team of PMs and became a Group Product Manager for the Protection team within Defender. That role lasted for a year before my team was merged into another and I ended up back as an IC PM. 🤷 The only constant is change.

Appendix: So, What Did PMs Do, Anyway?

When I first published this post, I felt unsatisfied because I think most folks who weren’t at Microsoft in the late 1990s and early 2000’s probably don’t have a clear idea of what the Microsoft PMs of my era actually did. That’s partly because PM was a fairly broad title covering a lot of different activities, and partly because not every PM performed every type of task.

Generally, however, a model PM would do many of the following things:

- Research and deeply understand customer problems.

- Analyze and deeply understand current competitive solutions.

- Brainstorm approaches to fix those problems and validate the proposals. Doing this effectively requires a comprehensive understanding of the capabilities of available technology (both hardware and software).

- Design great experiences to delight customers. In high-visibility flows, PMs will often have the help of dedicated writers, graphic designers, and usability researchers. However, those resources are often very limited, so a PM should be prepared to put together a shippable design without subject-matter-expert help, and obtain feedback to improve the design before the product ships.

- Make good tradeoffs and build consensus: whether it’s prioritizing feature investments, triaging bugs, or figuring out what dinner to order for folks staying late at the office.

- Communicate effectively, both narrowly (1:1 emails, small group meetings, etc) and broadly (blog posts, standards bodies, conference talks). This often involved translating between the varying jargon and interests of different audiences.

- Reduce Ambiguity. Even when a decision hasn’t yet been made or there’s not enough data, PMs work to ensure that everyone (dev, test, support, leadership, partner teams, etc) is on the same page about both the plan and the known unknowns.

- Be the Scribe. Any decision that has been made should be recorded (along with supporting data). Outstanding action items should be recorded and driven to closure.

None of these tasks are forbidden to Software Engineers, of course, but SWEs are expected to be world-class experts in writing code, a huge domain and a full-time job all its own.